Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

1

Statistical Digest of Rural England:

8 - Energy

May 2024

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

2

© Crown copyright 2024

You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under

the terms of the Open Government Licence v.3. To view this licence visit

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

or email

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at

rural.statistics@defra.gov.uk

www.gov.uk/defra

Cover photos

Ward 2011

Rural-Urban Classification

TL

Helmsley marketplace

Helmsley

Rural Village and Dispersed in a sparse setting

TC

Horton-in-Ribblesdale train

station with Penyghent behind

Penyghent Rural Village and Dispersed in a sparse setting

TR

St Giles Church, Skelton

Rural West York

Rural Town and Fringe

CL

Fishing Boat, Marske-by-the-

Sea with Hunt cliff in the

distance

St Germain's;

Saltburn

Rural Town and Fringe

CR

Thornton Force Waterfall,

Ingleton Waterfalls Trail

Ingleton and

Clapham

Rural Village and Dispersed in a sparse setting

BL

Farmer working the fields in

Knapton

Rural West York Rural Town and Fringe

BC

Remote pub at Ribblehead

viaduct

Ingleton and

Clapham

Rural Village and Dispersed in a sparse setting

BR

Glamping pod in the North

York Moors

Pickering East Rural Town and Fringe in a sparse setting

All cover photos provided by Martin Fowell.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

3

Contents

About the Statistical Digest of Rural England .................................................................................. 5

Official Statistics.............................................................................................................................. 6

Energy ............................................................................................................................................ 7

Fuel poverty - key findings ....................................................................................................... 8

Energy Performance Certificates: average Energy Efficiency Score - key findings................... 9

Energy Performance Certificates: achieving energy efficiency category C - key findings ....... 10

Energy costs - key findings .................................................................................................... 11

Energy consumption - key findings ........................................................................................ 12

A. Fuel poverty ...................................................................................................................... 13

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 13

Defining fuel poverty .............................................................................................................. 14

Fuel poor households ............................................................................................................ 16

Fuel poverty gap .................................................................................................................... 20

Fuel types used for central heating ........................................................................................ 23

Off the gas grid properties ...................................................................................................... 25

Fuel Poverty explanatory notes .............................................................................................. 29

B. Energy Performance Certificates: average Energy Efficiency Score .................................. 33

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 33

Energy Performance Certificates and ratings ......................................................................... 34

Average energy efficiency ...................................................................................................... 34

Average energy efficiency by housing age ............................................................................. 35

Average energy efficiency by housing type ............................................................................ 37

Average energy efficiency by tenure ...................................................................................... 40

Average energy efficiency distributions .................................................................................. 41

EPCs: average Energy Efficiency Score explanatory notes ................................................... 44

C. Energy Performance Certificates: achieving energy efficiency category C ......................... 46

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 46

Minimum energy efficiency of Category C and the link to fuel poverty .................................... 47

Progress towards achieving all homes having a minimum energy efficiency of Category C ... 47

Proportion of Category C properties by property age ............................................................. 48

Proportion of category C properties by property type and tenure ........................................... 52

EPCs: achieving energy efficiency Category C explanatory notes ......................................... 53

D. Energy Costs ..................................................................................................................... 55

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 55

Theoretical rather than actual energy costs ........................................................................... 56

Energy cost: New versus existing properties .......................................................................... 56

Energy cost: Housing type ..................................................................................................... 57

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

4

Energy cost: Housing tenure .................................................................................................. 58

Energy Costs explanatory notes ............................................................................................ 59

E. Energy Consumption ......................................................................................................... 61

Summary ............................................................................................................................... 61

Energy consumption data ...................................................................................................... 62

Energy consumption: Electricity ............................................................................................. 62

Energy consumption: Gas ...................................................................................................... 64

Energy Consumption explanatory notes ................................................................................. 66

Appendix 1: The 8 thematic reports that make up the Statistical Digest of Rural England (and the

topics included within them) .......................................................................................................... 68

Appendix 2: Defining Rural areas .................................................................................................. 69

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

5

About the Statistical Digest of Rural England

The Statistical Digest of Rural England (hereafter the Digest) is a collection of statistics on a range

of social and economic topics and provides broad comparisons between Rural and Urban areas by

settlement type. For more information on our classifications, including maps and diagrams

explaining the classification, see Appendix 2: Defining Rural areas.

The Digest has been restructured into thematic reports and incorporates the previously separate

publication the Rural Economic Bulletin.

The Digest consists of the following thematic reports:

1. Population

2. Housing

3. Health and Wellbeing

4. Communities and Households

5. Connectivity and Accessibility

6. Education, Qualifications and Training

7. Rural Economic Bulletin

8. Energy

In March 2024 the content relating to energy that was previously split across the Housing and

Communities and Households chapters has been consolidated into a new Energy report. Appendix

1, shows the sub-themes within each of the 8 Digest reports. Thematic reports will be updated

individually and not every report with be updated every month. The most recent updates for this

theme are shown in Table 1.

Please note: Energy Performance Certificates and Energy Cost and Consumption were initially

published as single sections and they were split when the new Energy report was created.

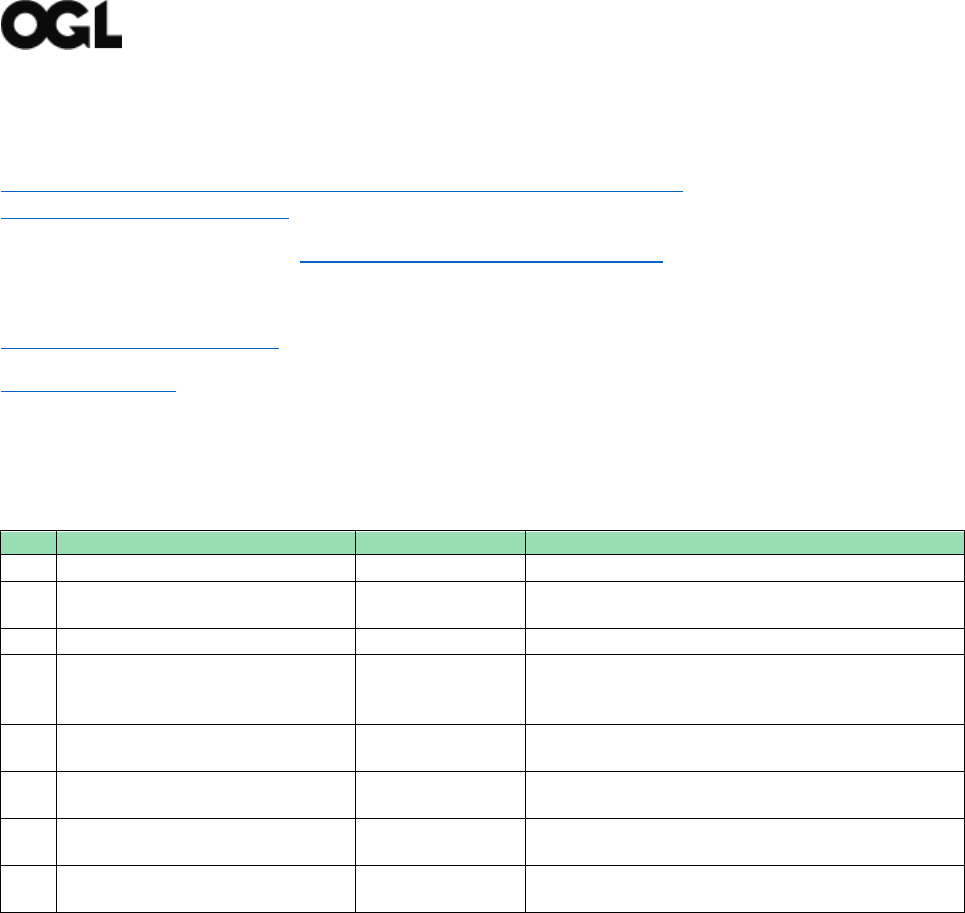

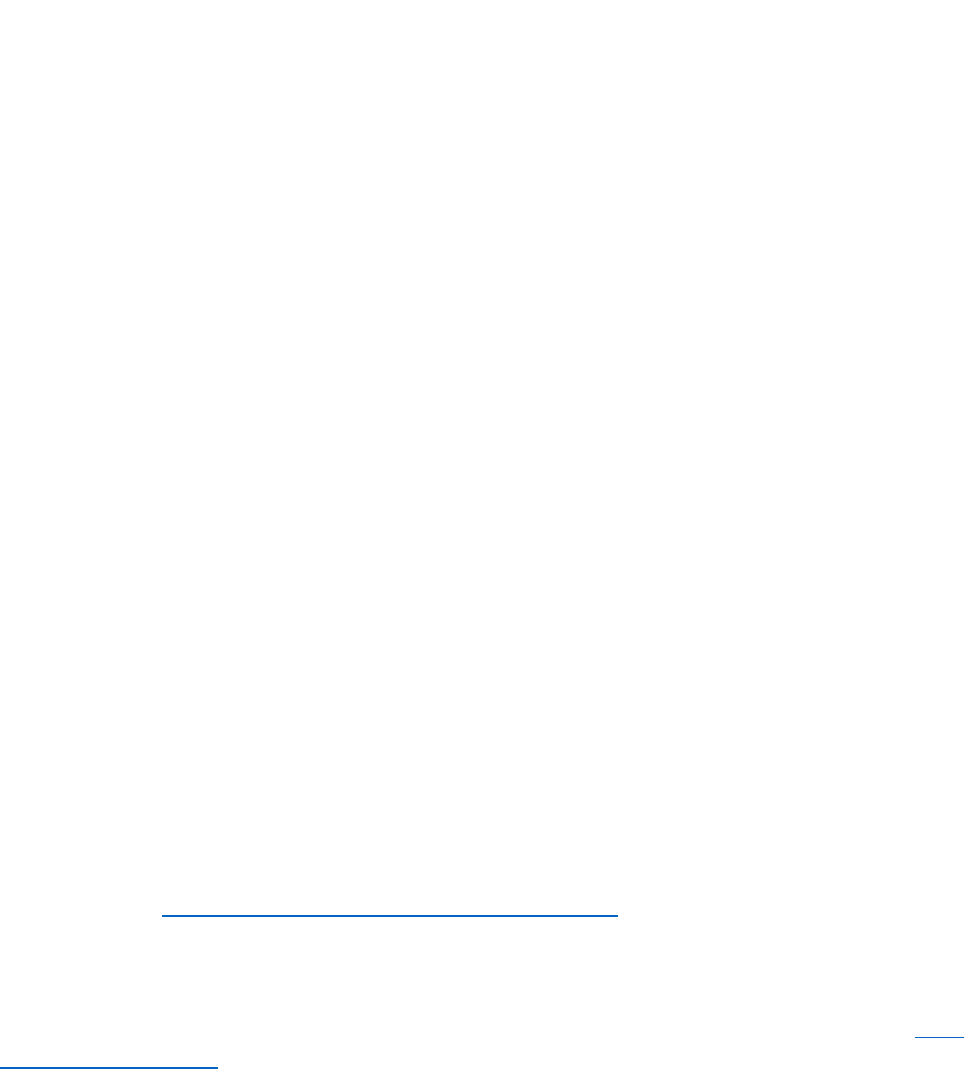

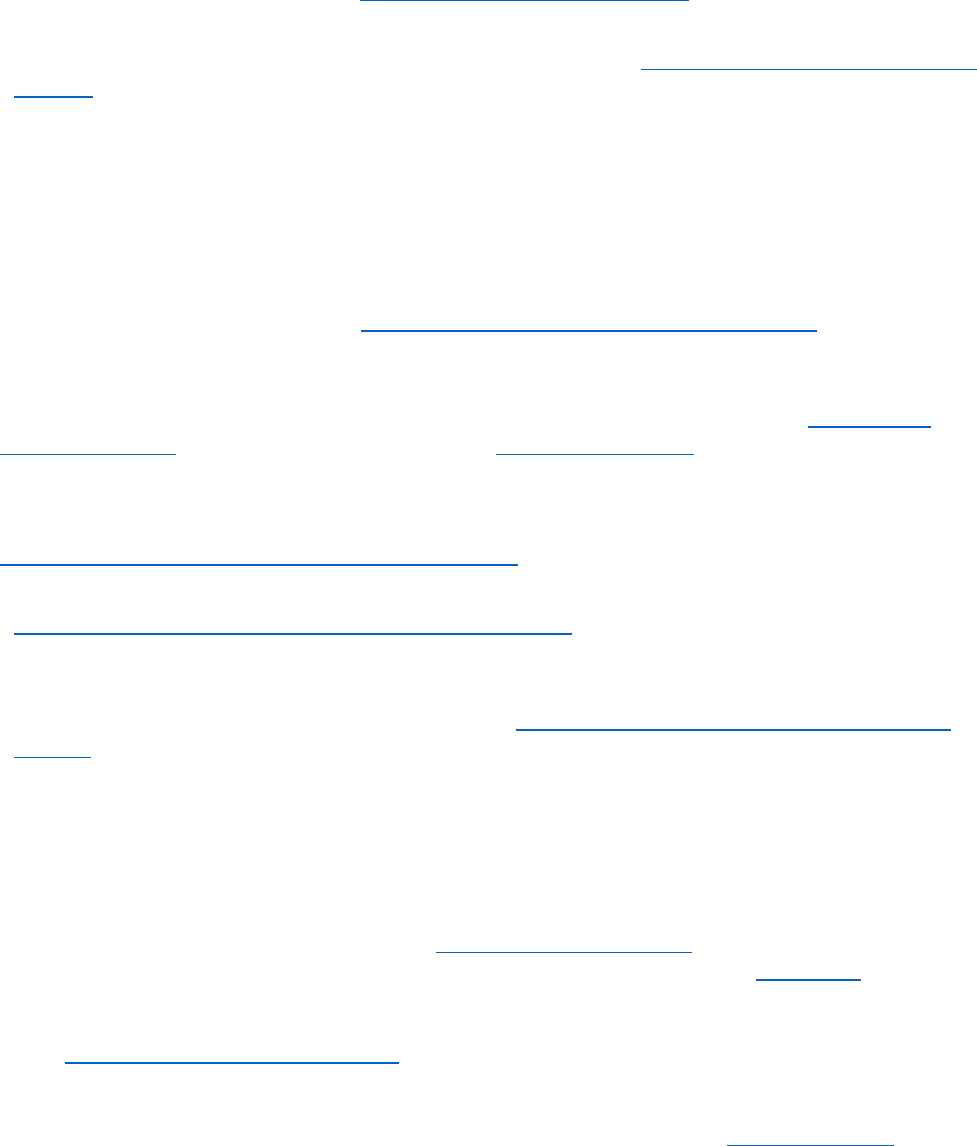

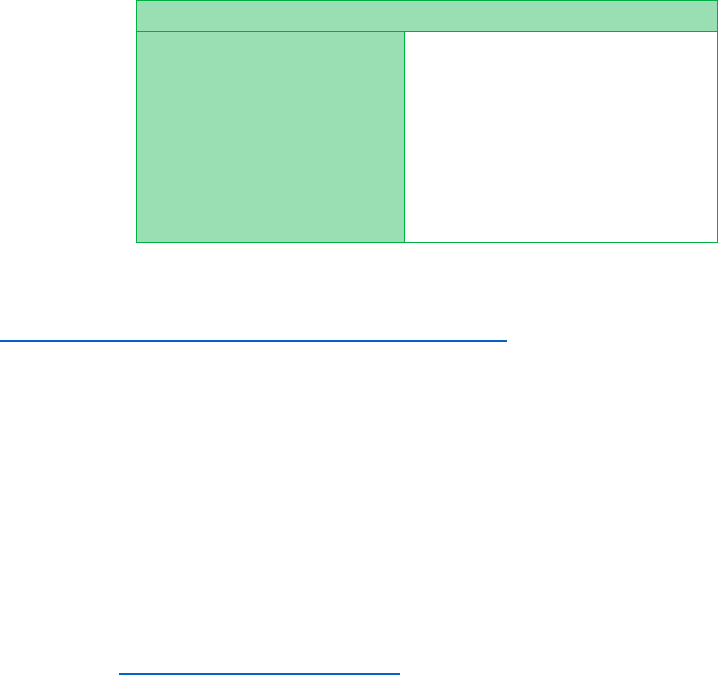

Table 1: Update monitor for Energy subsections

where “" indicates the topic has been updated, “" indicates the topic has not been updated,

and “New” indicates a new topic with analysis not previously included within the Digest.

Section April 2023 May 2023 August 2023 February 2024 May 2024

Fuel poverty

Energy Performance Certificates:

average Energy Efficiency Score

New

Energy Performance Certificates:

achieving energy efficiency

category C

New

Energy costs

New

Energy consumption

New

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

6

Official Statistics

These statistics have been produced to the high professional standards set out in the Code of

Practice for Official Statistics, which sets out eight principles including meeting user needs,

impartiality and objectivity, integrity, sound methods and assured quality, frankness and

accessibility.

More information on the Official Statistics Code of Practice can be found at:

Code of Practice for

Statistics.

This publication has been compiled by the Rural Statistics Team within the Rural and Place Team

in Defra:

Stephen Hall

Sarah Harriss

Beth Kerwin

Martin Fowell

rural.statistics@defra.gov.uk

There is a 2011 Census version of the Digest which looks at the data from the 2011 Census and

where possible makes comparisons to the 2001 Census results.

This can be found at

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/2011-census-results-for-rural-

england

Analysis of the 2021 Census will follow the release of a 2021-based Rural-Urban Classification.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

7

Energy

This part of the Statistical Digest of Rural England focuses on Housing, and covers the following:

• fuel poverty (Section A)

• average Energy Efficiency Scores from Energy Performance Certificates (Section B)

• properties achieving energy efficiency category C (Section C)

• energy costs (Section D)

• energy consumption (Section E)

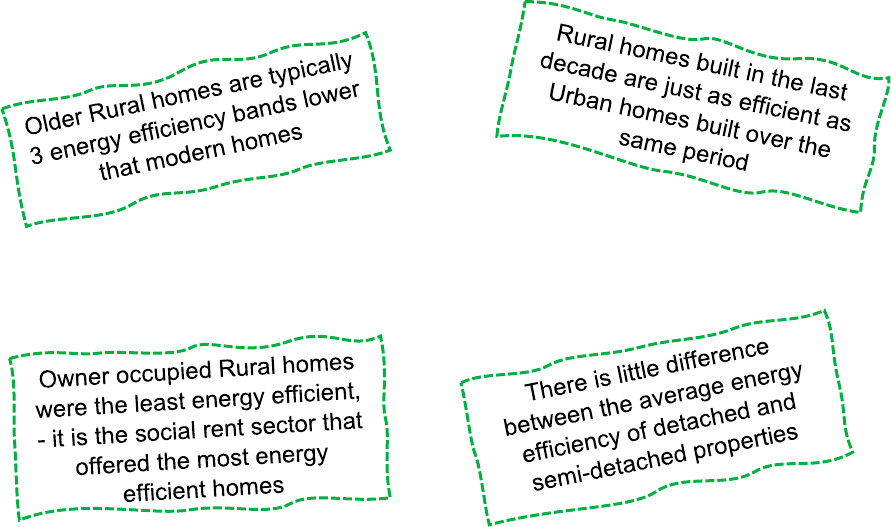

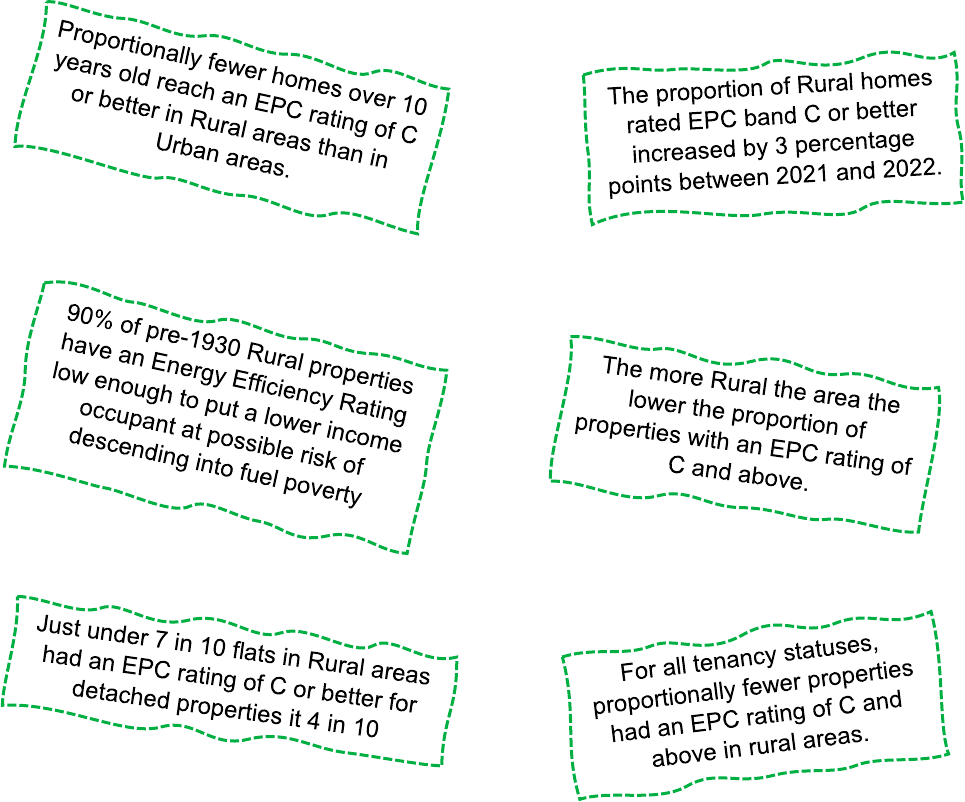

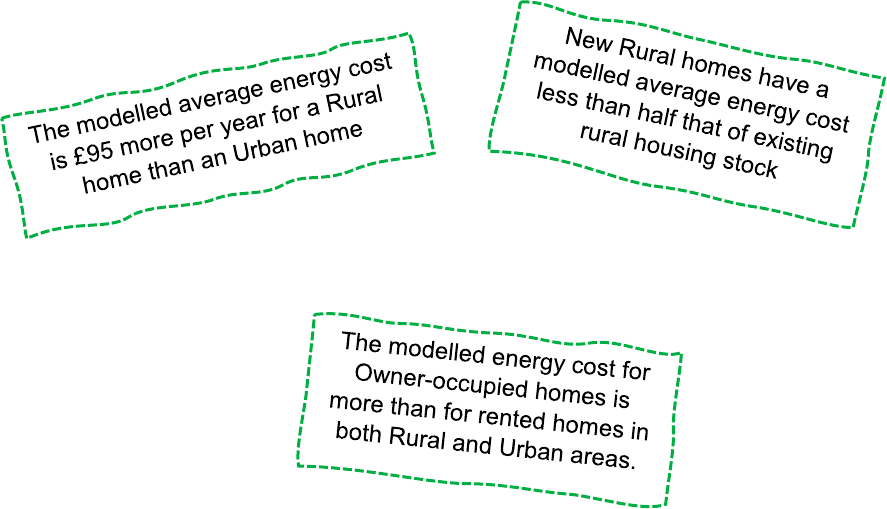

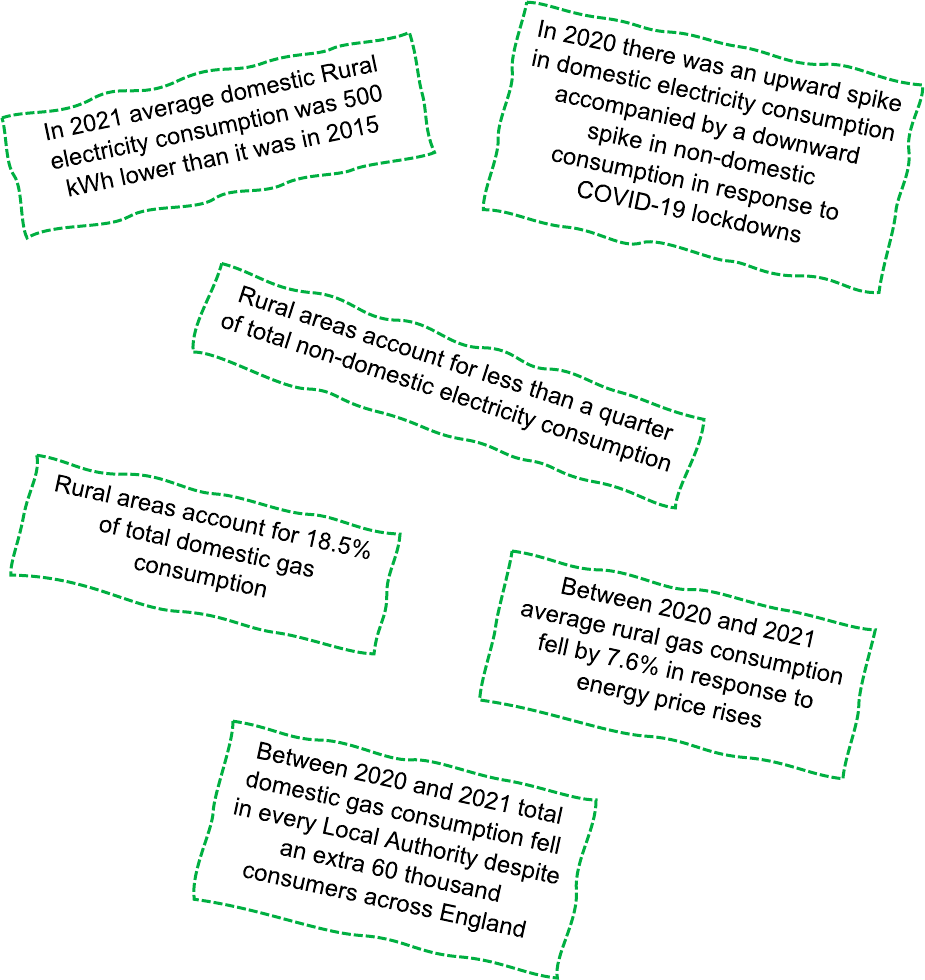

The key findings from this chapter are summarised with the following set of headline clouds:

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

8

Fuel poverty - key findings

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

9

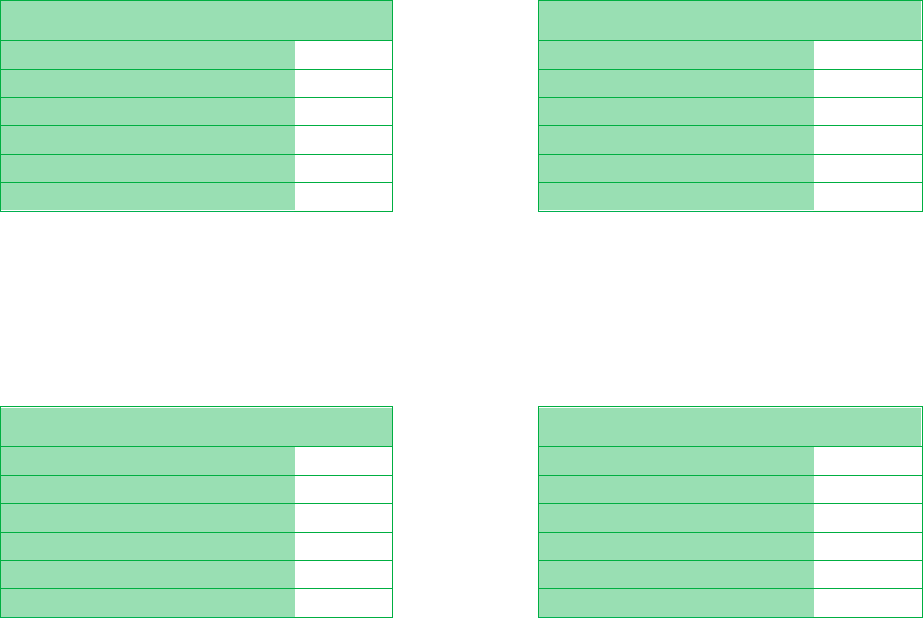

Energy Performance Certificates: average Energy Efficiency Score - key

findings

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

10

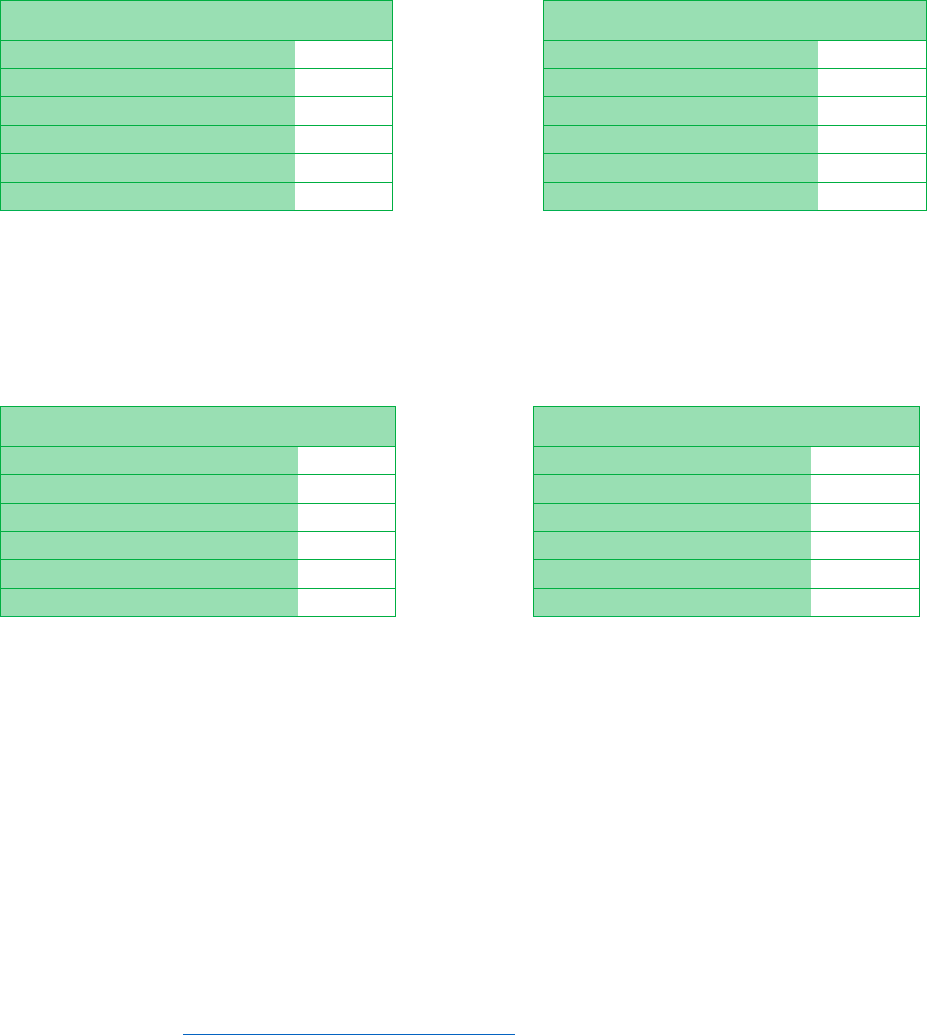

Energy Performance Certificates: achieving energy efficiency category

C - key findings

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

11

Energy costs - key findings

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

12

Energy consumption - key findings

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

13

A. Fuel poverty

There is a higher proportion of fuel poor households in Rural areas than in Urban areas and

the depth of the fuel poverty for these Rural households is greater, especially if their homes

are off the gas grid.

Summary

Households in fuel poverty are those living in a property with a Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency

Rating of band D or below in a home that cannot be kept warm at reasonable cost without bringing

their residual income below the poverty threshold. There are 3 key elements (drivers) in

determining whether a household is fuel poor: (1) household income; (2) household energy

efficiency; and (3) fuel prices. The fuel poverty gap (£) is an estimate of the depth of fuel poverty,

and it can be either the reduction in fuel costs or the increase in household income needed for a

household to not be in fuel poverty.

In 2023, the proportion of fuel poor households was higher in Rural areas (13.9%) than in Urban

areas (12.8%). This corresponds to 590,000 households in Rural areas. In Rural areas the

proportion of fuel poor households in 2023 is 2.3 percentage points higher than in 2019 (the first

year under the current methodology). By contrast in Urban areas the proportion of fuel poor

households was 1.1 percentage points lower in 2023 than it was in 2019. So, over the last 5 years,

levels of fuel poverty have risen in Rural areas, but they have fallen in Urban areas.

Households in Rural areas had an average fuel poverty gap of £568 in 2023 - this is £186 more

than the average fuel poverty gap of £382 in Urban areas. Over the last 5 years, the average fuel

poverty gap for Rural households has increased from £413 (in 2019) to £568 (in 2023), which is an

increase of £155 (or 38%). For the 62,000 fuel poor Rural households living in the least energy

efficient houses, the average fuel poverty gap was more than £1,800, whereas in 2019, the

average fuel poverty gap for those households living in these houses with the poorest energy

efficiency rating was £1,200.

The most common way of heating a home is through mains gas central heating. In Predominantly

Rural areas only 72% used mains gas in 2023 compared to 83% in Predominantly Urban areas. Oil

played a greater part in the heating fuel picture in Predominantly Rural areas (10% of homes) than

in Predominantly Urban areas (0.4% of homes).

In Predominantly Rural areas one in four properties (24.5%) were off the gas grid in 2022

compared to 11.5% in Predominantly Urban areas. Around a quarter of Predominantly Rural Local

Authorities have at least 35% of domestic properties off the gas grid. In absolute terms, 1.4 million

properties in Predominantly Rural areas are off the gas grid and this value has been stable over

the 2015 to 2021 period. Overall, there is a greater proportion of off-grid households in fuel poverty

than on-grid households and over the last decade more progress has been made in moving on-grid

households out of fuel poverty than for off-grid households. The depth of the fuel poverty for those

who are fuel poor is also greater when the household is off-grid rather than on it. In 2023 the

average fuel poverty gap for off-grid households was around £800 compared to around £320 for

on-grid households.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

14

Defining fuel poverty

Fuel poverty or being fuel poor is where a household is living in a property with a Fuel Poverty

Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) of band D or below in a home that cannot be kept warm at

reasonable cost without bringing their residual income below the poverty threshold. As explained in

Note A-5., there are therefore three key elements (drivers) in determining whether a household is

fuel poor: (1) household income; (2) household energy efficiency; and (3) fuel prices. The 2014 fuel

poverty target for England set an objective to ensure that as many fuel poor households as

reasonably practicable achieved a minimum energy efficiency rating of band C by 2030 (Note A-1)

Low Income High Costs (LIHC) was the preferred metric for measuring fuel poor households from

2011 to 2018. Note A-2

explains how LIHC was defined. For data representative of 2019 onwards

(Note A-3) the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) uses Low Income Low

Energy Efficiency (LILEE) as the preferred metric. Estimates for both metrics were produced for

2019 to allow a comparison.

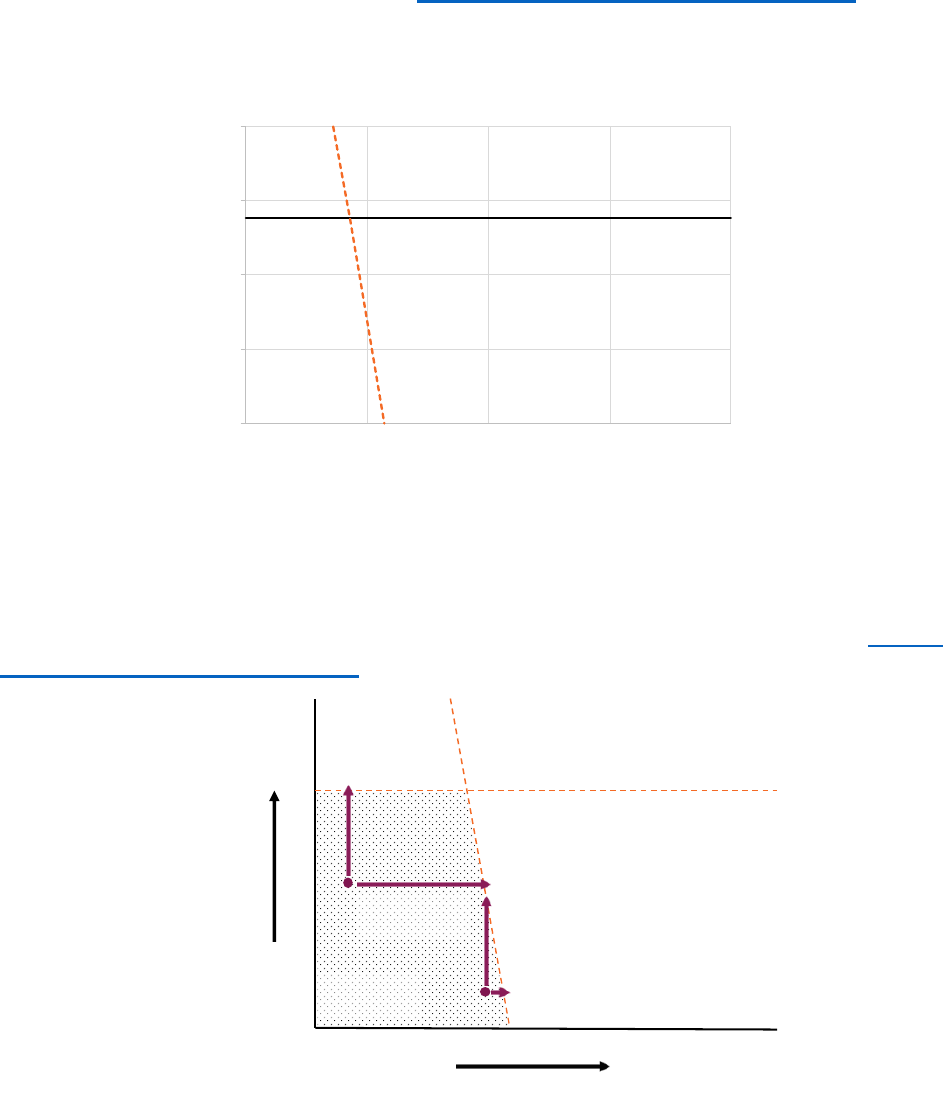

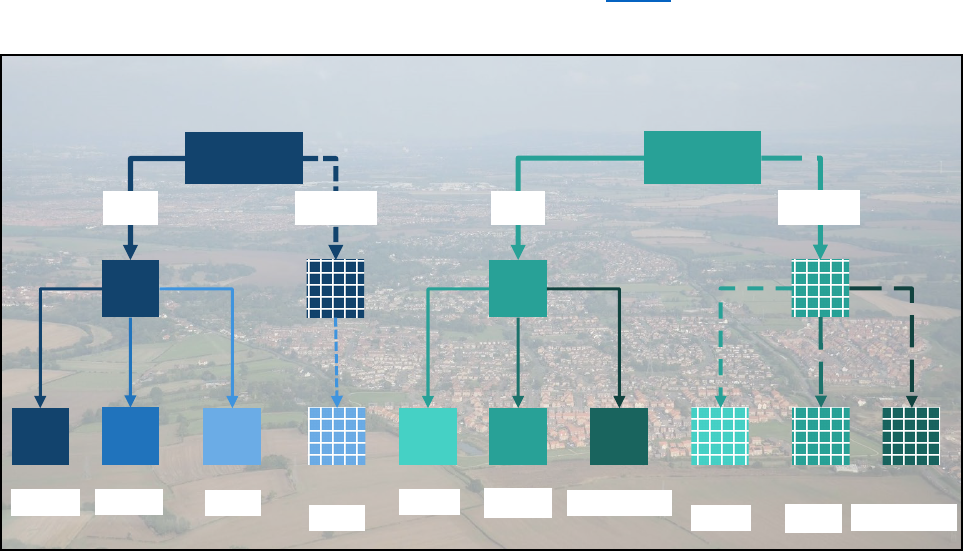

Based on household income and the energy efficiency of their home, all households can be divided

into 4 groups (Figure A-1). If their property FPEER is of band D (Note A-4) or below (under the

solid horizontal line on Figure A-1) they are defined as Low Energy Efficiency (LEE) and if the

FPEER is C or above they are defined as High Energy Efficiency (HEE). When assessing fuel

poverty, the income used in the assessment is the income available after housing costs, tax and

national insurance. The income threshold for fuel poverty is shown as a “best fit” sloped dashed

line on Figure A-1. The line is sloped because the less energy efficient the home the greater the

impact of fuel costs on available income. Households to the left of the sloped line are defined Low

Income (LI) and those to the right of the line are defined as High Income (HI). The lower left group

therefore becomes Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE), these are the fuel poor

households. In 2023 13.0% of households in England were defined as fuel poor. Note A-5 provides

more details on the LILEE methodology.

The fuel poverty gap is an estimate of the depth of fuel poverty. The fuel poverty gap is the

reduction in fuel costs needed for a household to not be in fuel poverty. As shown in Figure A-2 a

household can escape fuel poverty by increasing the energy efficiency of their home to a FPEER

of at least Band C or by crossing the income threshold. Crossing the income threshold could be

achieved by increasing the absolute household income through things like gaining employment or

increasing their salary by getting a better paid job or government intervention.

Using the two example households in Figure A-2, one household is in a home that is very energy

inefficient, but their household income is close to the income threshold. For this type of household

reducing fuel costs or increasing income brings them out of fuel poverty more easily than by

increasing the efficiency of their home. The second illustrative household has very Low Income but

a more efficient home than the first example. For this household improving energy efficiency would

move them out of fuel poverty.

As shown in the Statistical Digest of Rural England:2 – Housing

, housing in Rural areas is more

likely to be detached and much less likely to be flats than in Urban areas. There is also a higher

proportion of Rural housing that is more than 100 years old (

Note A-6). In 2019 the Energy Savings

Trust stated that nearly 20% of homes in rural areas are in the very energy inefficient F and G

categories, compared to just 2.4% in urban areas (Note A-7). Figures from the DESNZ / BEIS 2022

Fuel Poverty Statistics suggest that this 20% is an overestimate. These 2023 figures show that

6.8% of Rural households are living in properties that are rated F or G compared to 1.4% of

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

15

households in Urban areas. More information on the energy efficiency of homes can be found in

the Energy Performance Certificates sections of this report (Section B and C).

In Predominantly Rural areas there is also a greater reliance on heating oil than in Predominantly

Urban areas - see the “Fuel types used for central heating” section. Unlike domestic gas prices,

there is no cap on domestic oil prices, so there is the potential for it to be more expensive to heat a

home with heating oil than gas.

Figure A-1: A schematic diagram to show how fuel poor households were defined in 2023

The numbers in percentages are the proportion of households in 2023 in each of the 4 groups.

This diagram is based on Figure 2.2 in the Annual fuel poverty statistics report: 2024

publication. FPEER on the Y-axes is Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating. LI and HI are High and

Low Income respectively. HEE and LEE are High and Low Energy Efficiency respectively.

Figure A-2: A schematic diagram representing the fuel poverty gap

The hatched area represents those households in fuel poverty and the arrows represent the

property energy efficiency or household income gains that 2 households (represented by the small

circles) would need to make to exit fuel poverty. This diagram is based on Figure 1 in the Annual

fuel poverty statistics report: 2023 publication.

0

25

50

75

100

0 20,000

40,000 60,000

80,000

FPEER

Income (£)

LILEE

(fuel poor)

13.0%

HILEE

36.4%

HIHEE

35.4%

LIHEE

15.2%

Energy Efficiency

Band C

Income threshold

Increasing

FPEER

Increasing household income

Energy Efficiency

Band C

Income threshold (£)

LILEE Fuel

Poverty

Fuel Poverty

Gap

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

16

Fuel poor households

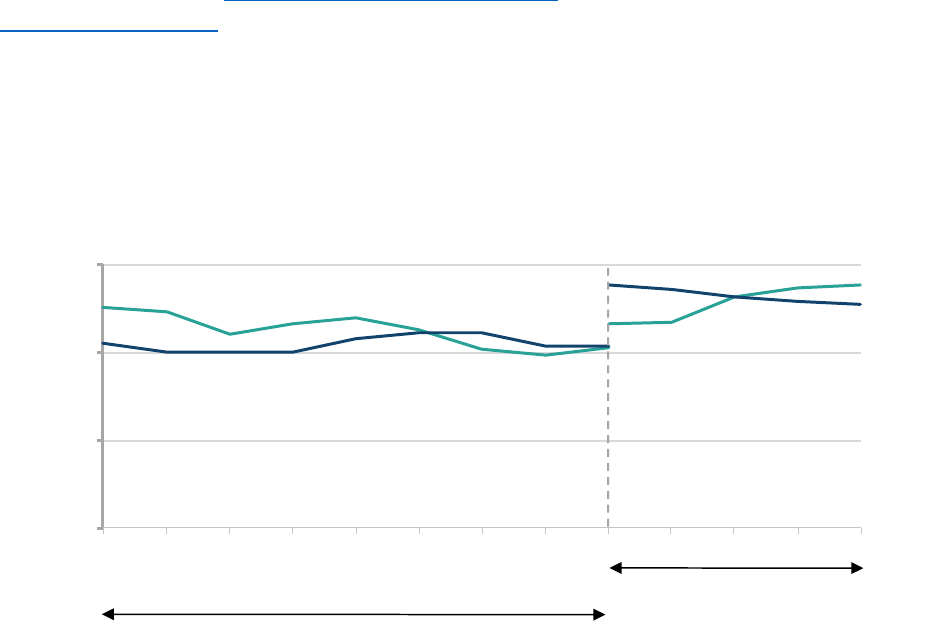

There were 3.2 million fuel poor households in England in 2023 (see Figure A-1 for a definition of

fuel poor). In Rural areas there was 590 thousand fuel poor households and in Urban areas there

was 2.6 million fuel poor households. As Figure A-3 shows, historically between 2011 and 2015

fuel poverty was proportionately more prevalent in Rural areas than in Urban areas under the old

LIHC metric. In 2017 and 2018 fuel poverty was marginally more prevalent in Urban areas than in

Rural. In 2019 under LIHC there was 10% of households in fuel poverty in both Rural and Urban

areas.

The change of in methodology from LIHC to LILEE as the preferred metric resulted in increases of

1.3 percentage points in fuel poor Rural households and 3.4 percentage points in fuel poor Urban

households (Figure A-3). Unlike some other variables a consistent time series under the LILEE is

not included within the long-term fuel poverty trend tables

that are updated annually as part of the

Fuel Poverty Statistics publication (Note A-8).

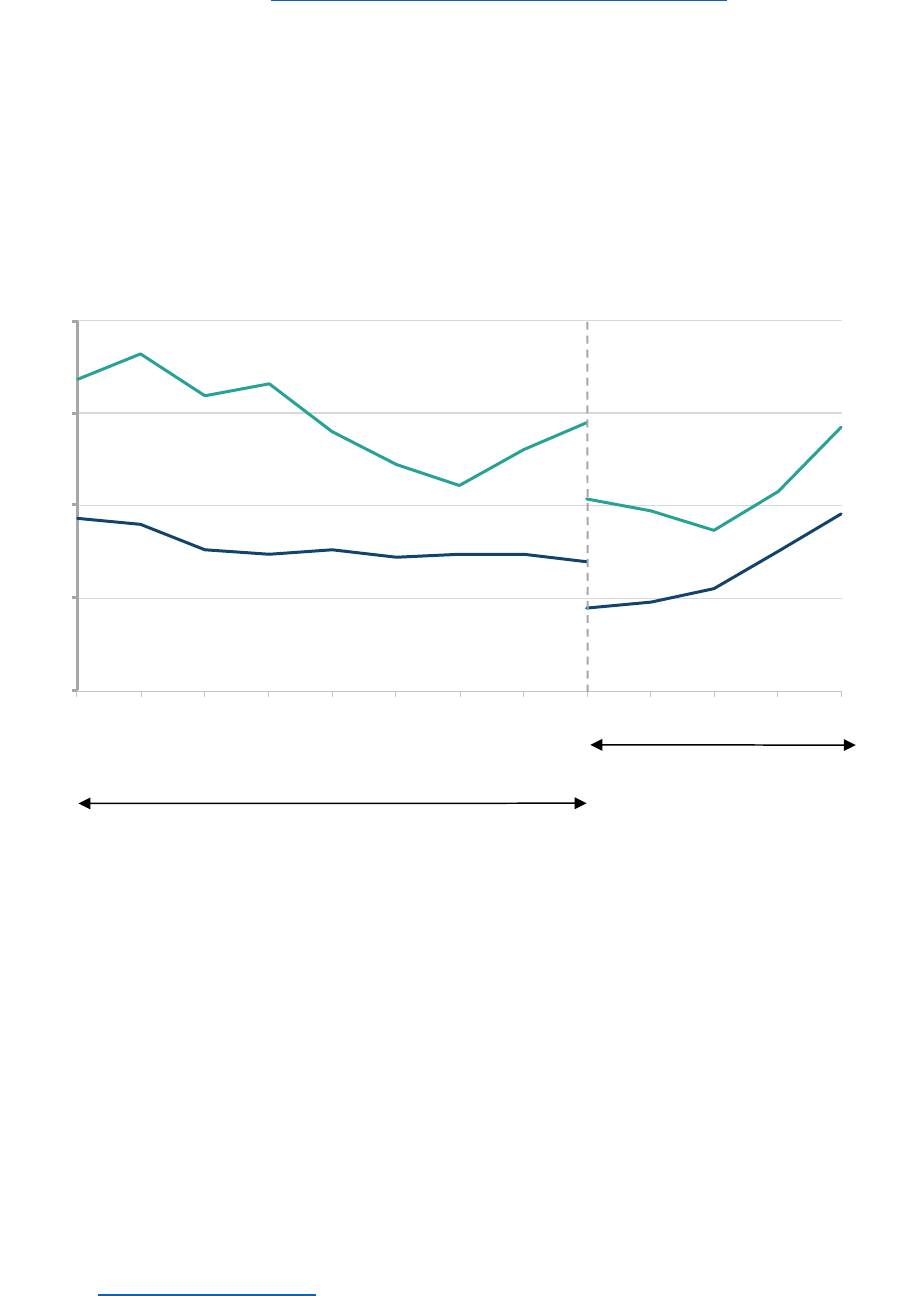

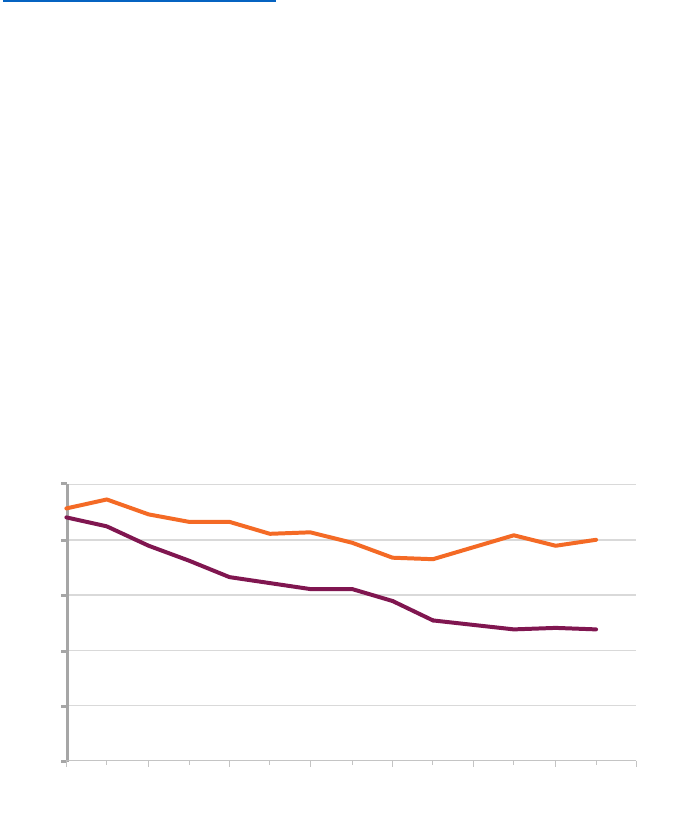

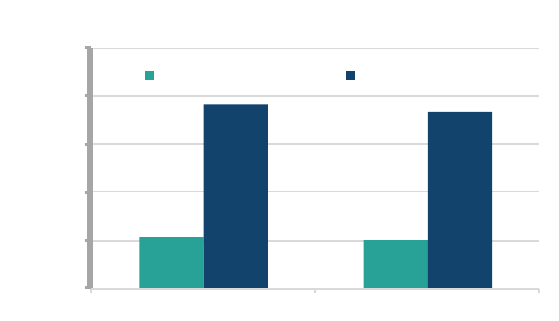

Figure A-3: Line chart showing the proportion of fuel poor households (%) in Rural and

Urban areas (2011 to 2023).

Low Income High Costs (LIHC) was the preferred metric from 2011 to 2018 (Note A-2). From 2019

onwards Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) became the preferred metric (Note A-5). The

series break for the change in methodology is shown by a dashed vertical line.

Under LILEE fuel poverty was more prevalent in Urban areas than in Rural in 2019 and 2020. In

2021 the proportion of Rural households in fuel poverty rose while falling in Urban areas and the

proportion of fuel poor households was 13.1% in both Rural and Urban areas. In both 2022 and

2023 the proportion of fuel poor households was higher in Rural areas than in Urban areas. In

2023 13.9% of Rural households were fuel poor compared to 12.8% of Urban households. This

means that in 2023 there were 590,000 fuel poor households in Rural areas.

Comparing 2023 to 2019 (the first year under LILEE), we see that the proportion of fuel poor

households in Rural areas in 2023 is 2.3 percentage points higher than in 2019. By contrast in

Urban areas the proportion of fuel poor households was 1.1 percentage points lower in 2023 than it

was in 2019. In other words, over the last 5 years, levels of fuel poverty have fallen in Urban areas,

but they have risen in Rural areas. Note that over the last 12 months the proportion of fuel poor in

Rural areas has gone up by 0.2 percentage points, while it has gone down by 0.2 percentage

points in Urban areas.

0

%

5%

10%

15

%

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023

LIHC m etric

LILEE metric

Urban

Rural

Methodological change

Rural

Urban

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

17

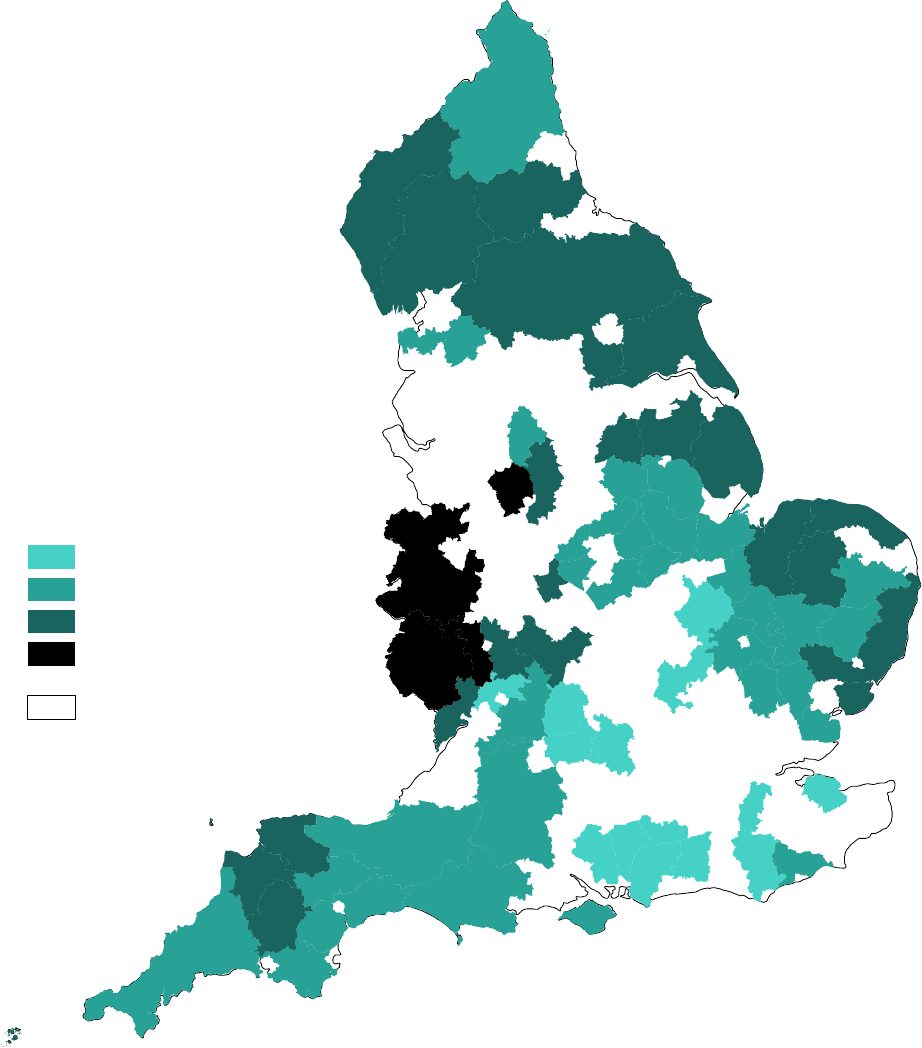

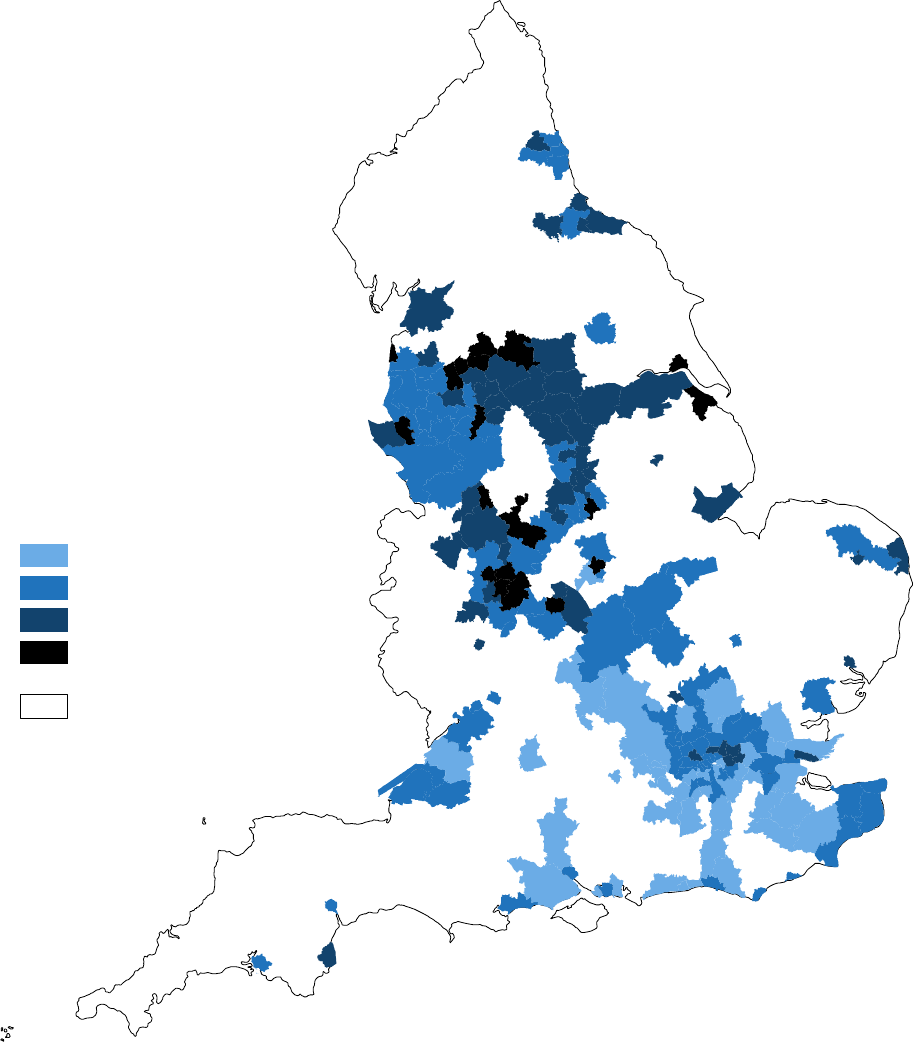

DESNZ produces sub-regional fuel poverty data as Experimental Statistics (Note A-15). Estimates

at the sub-regional level are modelled using proxy indicators available for low level geographies

and should only be used to look at general trends and identify areas of particularly high or low fuel

poverty. They should not be used to identify detailed trends over time. In 2013, BEIS undertook an

internal review of the methodology used to produce sub-regional estimates of fuel poverty, in

conjunction with Office for National Statistics (ONS) Methodology Advisory Service. This review

found that estimates of fuel poverty were robust at Local Authority level, but not robust at lower

levels of geography. We are therefore introducing Rural and Urban maps of the proportion of

households in fuel poverty at Local Authority level (Figure A-4 and Figure A-5) to the Digest, but

will not be producing them at more detailed levels of geography. At the time of producing this

update DESNZ has not released any more recent sub-regional fuel poverty data, therefore Figure

A-4 and Figure A-5 have not been revised.

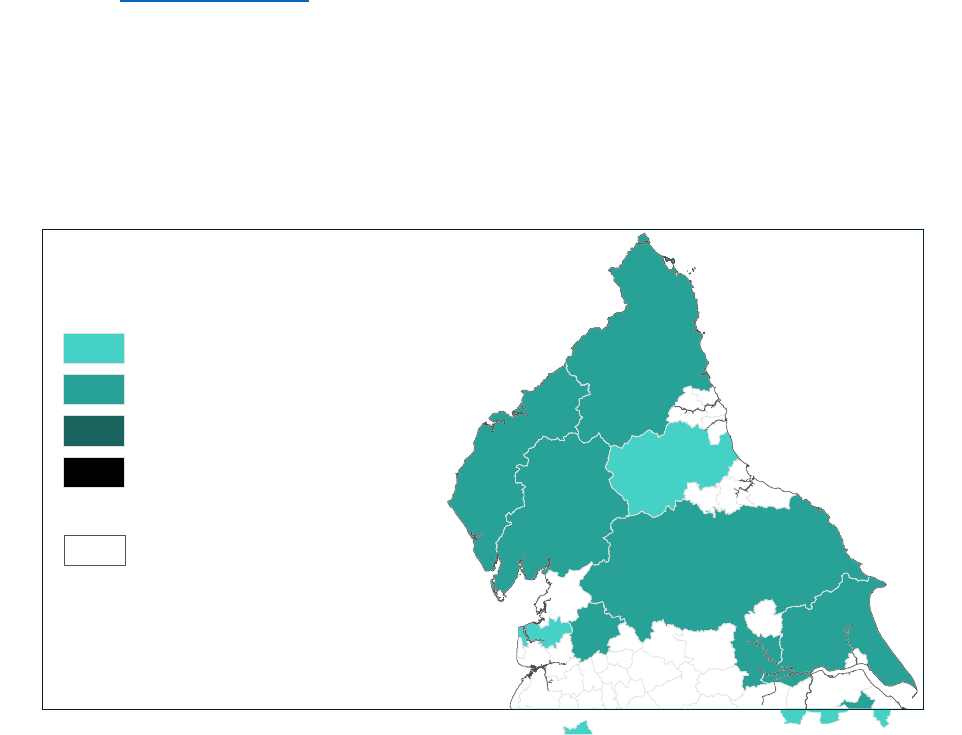

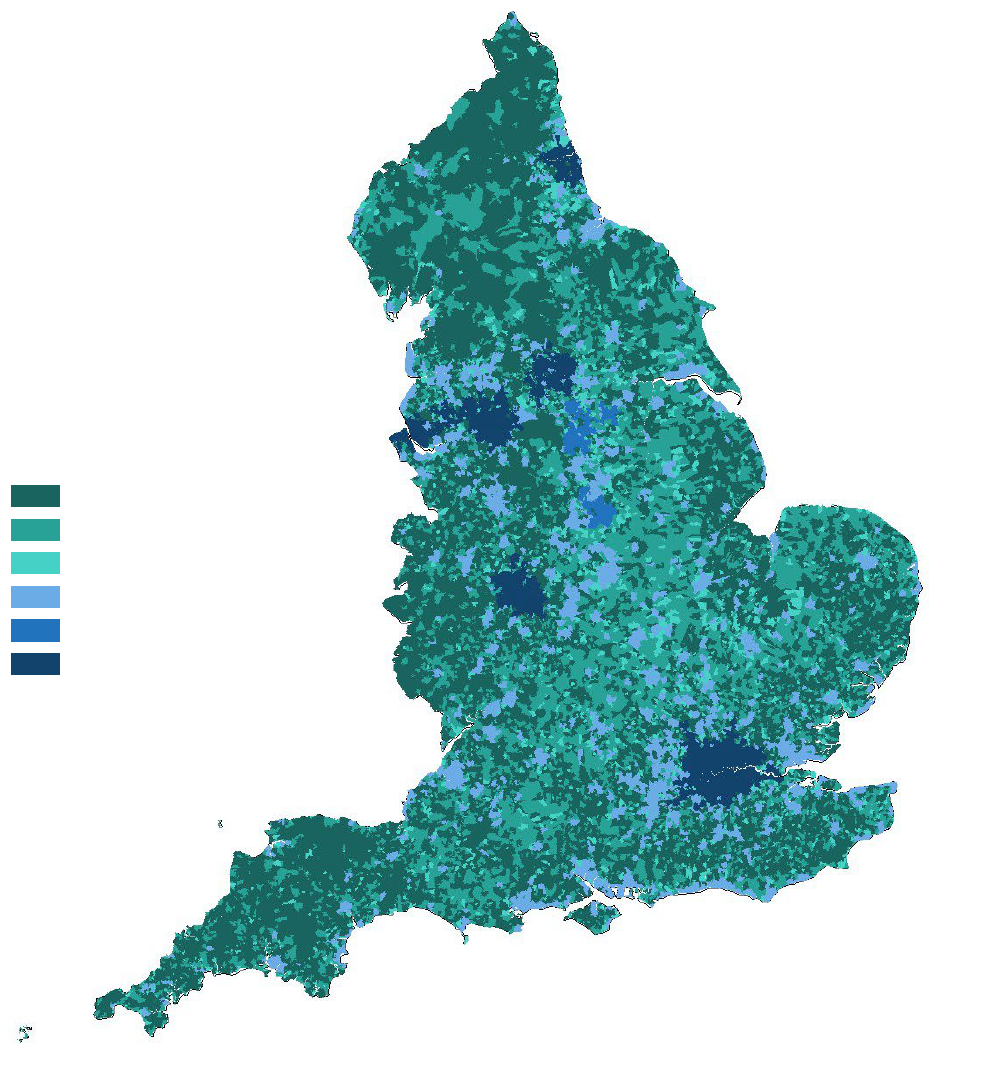

Within Rural areas (Figure A-4) the proportion of households classified as fuel poor is highest in

the Local Authorities along the England and Wales border. Local Authority boundaries changed in

April 2023 in both North Yorkshire and Cumbria. This has reduced the number of Local Authorities

in the North (Note A-16). Using these new boundaries, north of the Humber only three Local

Authorities have less than 14% of households in fuel poverty. In East Anglia there are

proportionally more households in fuel poverty in coastal Local Authorities than in those further

inland. Proportionally more households are in fuel poverty in the three Local Authorities making up

northern and western Devon than in other Local Authorities in South West England. Within the

East Midlands region there is proportionally more fuel poverty in Northern and Eastern Lincolnshire

and in much of Derbyshire than in southern parts of this region.

In summary, Figure A-4 shows Rural fuel poverty is above average in in Cumbria, Yorkshire,

Durham, Lincolnshire, coastal areas of East Anglia, along the England / Wales border and in north

west Devon and below average Rural fuel poverty in the Local Authorities of the South East region.

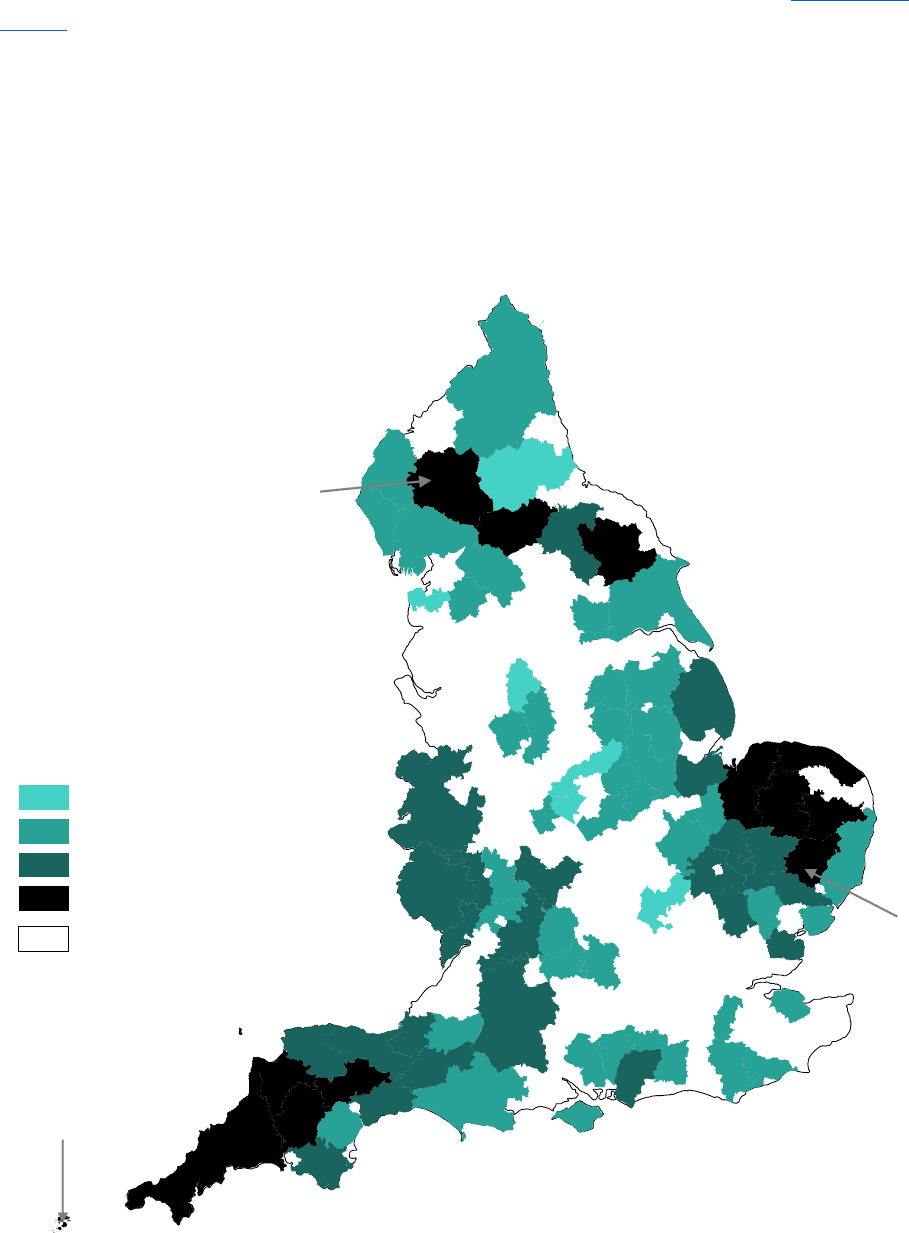

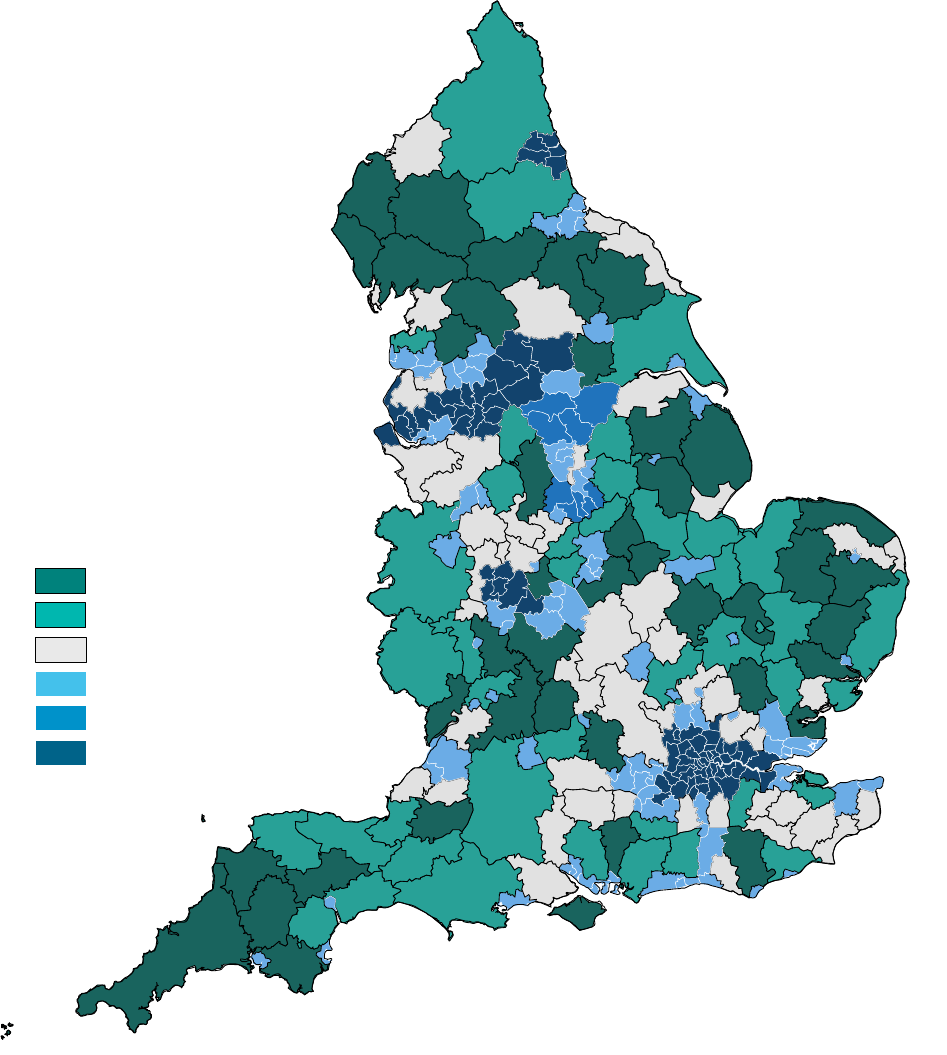

Figure A-5 shows the proportion of households classified as fuel poor in Urban Local Authorities. In

general terms, as for Rural areas, Local Authorities with below average fuel poverty tend to be in

the South East and those with above average fuel poverty tend to be in the North or the Midlands.

Notable exceptions in the South East are above average fuel poverty in parts of central London. In

the North East there is proportionally more fuel poverty on Teesside than in Tyne and Wear.

Within Yorkshire and the Humber, York has lower levels of fuel poverty than the Urban authorities

of South and West Yorkshire. In general, Local Authorities in the North West have lower levels of

fuel poverty than in Yorkshire and the Humber, particularly in the south and centre of the area.

However, there are still pockets of higher fuel poverty such as on Merseyside and in northern and

eastern parts of the area such as Blackpool and Burnley. Of the six Urban Local Authorities where

more than 20% of households are fuel poor, five are in the West Midlands.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

18

Figure A-4: Map of the proportion (%) of households in Rural areas that are fuel poor

according to the LILEE definition in 2021

The darker the shading the higher the proportion of households that are fuel poor. White areas on

the map and Predominantly Urban or Urban with Significant Rural areas. This map uses Local

Authority boundaries applicable from 1 April 2023. At the time of producing this update DESNZ

have not released any more recent sub-regional fuel poverty data, therefore this map has not been

revised. (Note A-15, Note A-16)

P r o p o r t i o n o f h o u s e h o l d s c l a s s e d

a s f u e l p o o

r

i n R u r a l a r e a s

P r e d o m i n a n t l y U r b a n , o r

U r b a n w i t h S i g n i f i c a n t R u r a l

L e s s t h a n 1 0 %

1 0 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 1 4 %

1 4 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 1 8 %

1 8 % o r m o r e

© C r o w n C o p y r i g h t a n d d a t a b a s e r i g h t s 2 0 2 3

O r d n a n c e S u r v e y L i c e n c e N o . 1 0 0 0 2 2 8 6 1

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

19

Figure A-5: Map of the proportion (%) of households in Urban areas that are fuel poor

according to the LILEE definition in 2021

The darker the shading the higher the proportion of Urban households that are fuel poor. White

areas on the map are Predominantly Rural. This map uses Local Authority boundaries applicable

from 1 April 2023. At the time of producing this update DESNZ have not released any more recent

sub-regional fuel poverty data, therefore this map has not been revised. (Note A-15, Note A-16)

© C r o w n C o p y r i g h t a n d d a t a b a s e r i g h t s 2 0 2 3

O r d n a n c e S u r v e y L i c e n c e N o . 1 0 0 0 2 2 8 6 1

P r o p o r t i o n o f h o u s e h o l d s c l a s s e d

a s f

u

e l p o o

r

i n U r b a n a r e a s

L e s s t h a n 1 0 %

1 0 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 1 4 %

1 4 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 1 8 %

1 8 % o r m o r e

P r e d o m i n a n t l y R u r a l

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

20

Notes

• DESNZ / BEIS changed their preferred fuel poor metric from Low Income High Costs (LIHC) to Low

Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE). Note A-5 explains how LILEE is calculated. In 2019 DESNZ /

BEIS produced both estimates, so both are shown on Figure A-3. The dashed line represents the

change of metric.

• In Sub-regional fuel poverty 2023 (2021 data)

published in April 2023 DESNZ published on the basis of

the Local Authorities that applied from 1 April 2023 despite the data being representative of 2021. This

means that unlike other analysis in the Digest,

Figure A-4 and Figure A-5 are on the basis of only 296

Local Authorities rather than the 309 detailed in Appendix 1: Defining Rural areas. At the time of

preparing the most recent update 2021 was the most recent sub-regional data available.

Fuel poverty gap

As explained in the “Defining fuel poverty” section, the fuel poverty gap (£) is an estimate of the

depth of fuel poverty, and it can be either the reduction in fuel costs or the increase in household

income needed for a household to not be in fuel poverty. Figure A-6 shows that over the period

2011 to 2023 the average fuel poverty gap (or depth of the fuel poverty) was greater in Rural areas

than in Urban areas in every year over this 13-year period. The change of methodology does not

affect this conclusion, but the average difference between the Rural and Urban fuel poverty gaps

was bigger for the years covered by LIHC (average difference between Rural and Urban gaps of

£278) than for the period from 2019 onwards under LILEE (average difference between Rural and

Urban gaps of £174). In England, the average fuel poverty gap for households that were fuel poor

in 2023 was £417, this is an increase compared to 2022 when it was £325.

DESNZ have revised their estimates of the fuel poverty gap in 2022 for Rural areas downwards.

Their initial estimate published in 2023 showed that households in Rural areas had an average fuel

poverty gap of £677 in 2022. In the February 2024 release they showed that households in Rural

areas had an average fuel poverty gap of £432 in 2022 – almost £250 less that the initial release.

By contrast DESNZ have revised the average fuel poverty gap for households in Urban areas

upwards to £302. This means that in 2022 the fuel poverty gap was £130 (or over 40%) deeper in

Rural areas than in Urban areas. The fuel poverty gap for fuel poor households in Rural Villages,

Hamlets and Isolated Dwellings in 2022 was a large contributor to this revision because it was

revised down from £956 to £569. There is a table showing fuel poverty figures by RUC category in

Energy data tables

.

In 2023 the average fuel poverty gap for households in Rural areas was £568, this is £186 more

than the average fuel poverty gap of £382 in Urban areas. So, in 2023 fuel poverty was almost

50% deeper in Rural areas than in Urban areas. The fuel poverty gap for fuel poor households in

Rural Villages, Hamlets and Isolated Dwellings in 2023 was £778.

The average fuel poverty gap in 2023 in Rural areas was £136 more than it was in 2022 (32%

higher), whereas for Urban areas it was only £80 more than in 2022 (26% higher). When the

comparison is made to 2019 (the first year under LILEE) we see that the average fuel poverty gap

for Rural households has increased from £413 to £568, which is an increase of £155 (or 38%). By

contrast for Urban households the fuel poverty gap has more than doubled, increasing from £180

in 2019 to £382 in 2023.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

21

The increasing depth of fuel poverty is a response to the rising energy costs in recent years. The

fact that the depth of the fuel poverty in Rural areas has risen more than in Urban areas over the

last 12 months is likely to be as a consequence of houses in Rural areas being typically larger, and

often older, than Urban ones (Statistical Digest of Rural England:2 – Housing

). These two factors

make them less energy efficient (sections B and C) and therefore more costly to heat (Section D).

In other words, the more units of energy you use to heat your home the more you are affected by

the increased cost of each of those energy units.

Figure A-6: Line chart showing the average fuel poverty gap (£) in Rural and Urban areas

(2011 to 2023).

Low Income High Costs (LIHC) was the preferred metric from 2011 to 2018 (Note A-2). From 2019

onwards Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) became the preferred metric (Note A-5). The

series break for the change in methodology is shown by a dashed vertical line

Using the previous LIHC metric the average fuel poverty gap for Urban households decreased

between 2011 and 2019, while for Rural households the gap also decreased between 2012 and

2017, but the Rural fuel poverty gap then deepened between 2017 and 2019 (Figure A-6).

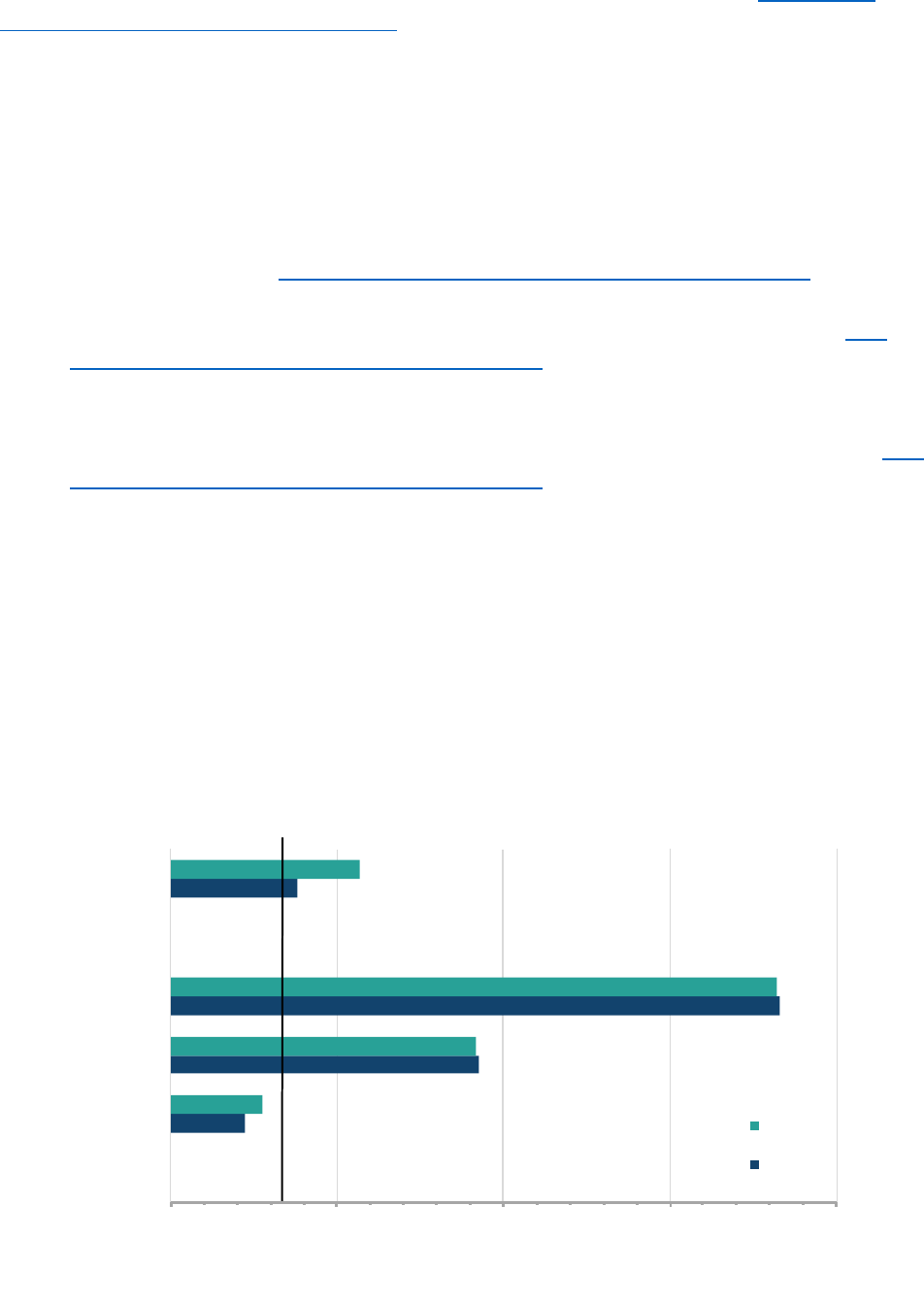

The Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) is a measure of the energy efficiency of a

property (Note A-4). As shown on Figure A-7, in 2023 Rural households with the poorest FPEER

rating of F or G had an average fuel poverty gap of over £1,800, which is similar to the average

fuel poverty gap for Urban households of the same energy rating. In the revised 2022 figures the

average fuel poverty gap for those Rural households in homes with the poorest FPEER rating of F

or G was £1,300. For further context in 2019, the average fuel poverty gap for those households

living in these houses with the poorest energy efficiency rating was £1,200 in Rural areas and £860

in Urban areas. 290,000 Rural households still lived in the least energy efficient homes in 2023; the

62,000 of those who are in fuel poverty have seen the depth of their fuel poverty increase

substantially in a very short time period because energy costs have risen rapidly.

In the latest Fuel Poverty Statistics DESNZ consider fuel poverty by property characteristics (

Note

A-9). DESNZ reported that the fuel poverty gap was largest for converted flats (£597) and

£0

£200

£400

£600

£800

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023

LIHC m etric

LILEE metric

Rural

Urban

Methodological changeAverage fuel poverty gap

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

22

households living in converted flats were more likely to be in fuel poverty than households in any

other property type. The average fuel poverty gap for households in detached properties was the

only other one that exceeded £500. Comparing an end terrace to a mid-terrace (

Fuel poverty

detailed tables 2024 (2023 data) - Table 7) shows that 3.3% fewer households in a mid-terrace are

in fuel poverty than for households in an end terrace and when the households are fuel poor the

average depth of the fuel poverty is £127 less for a mid-terrace than an end terrace. This matters

in a rural context because the average urban terrace is 50% longer than the average rural terrace,

so there are proportionally fewer mid terraced properties in rural areas (

Note A-6).

DESNZ also report that:

• the average depth of fuel poverty is higher for households in properties with solid walls than

for those in homes with cavity walls, even if the solid walls have been insulated and the

cavity walls have not (Fuel poverty detailed tables 2024 (2023 data) - Table 15

);

• the larger the floor area the higher the average fuel poverty gap for fuel poor residents, with

the value reaching £554 for households in properties with floor areas over 110m

2

(Fuel

poverty detailed tables 2024 (2023 data) - Table 9); and

• the depth of fuel poverty is much higher for households in pre-1919 properties (£575) than

for households in properties built after this date, but it is not correct to assume that the

newer the property the lower the average fuel poverty gap for any fuel poor residents (

Fuel

poverty detailed tables 2024 (2023 data) - Table 8).

All 3 of these property characteristics (solid walls, bigger and older properties) are more prevalent

in Rural areas than Urban areas. For example, there are over 1 million pre-1919 homes in rural

areas and they account for 28% of rural residential properties compared to only 18% of urban

residential properties (Note A-6).

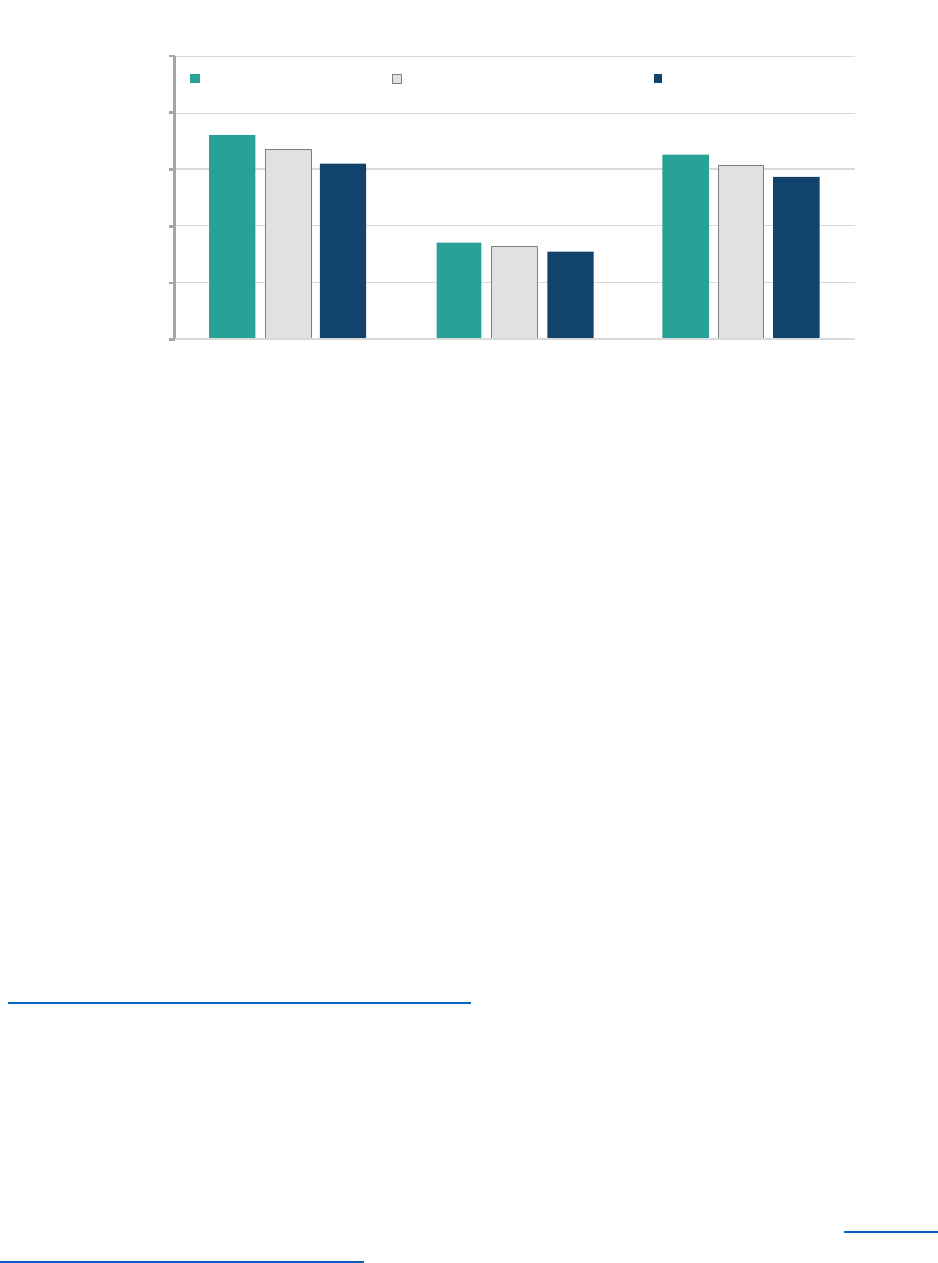

Figure A-7: Bar chart showing average fuel poverty gap (£) in Rural and Urban areas in 2023

according to Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) band

(Note A-2, Note A-4, Note A-5)

The legend is presented in the same order as the clusters of bars.

0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000

A/B/C

D

E

F/G

All

Average fuel poverty gap (£)

FPEER band

Rural

Urban

Average fuel poverty gap in England (£417)

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

23

Notes

• DESNZ / BEIS changed their preferred fuel poor metric from Low Income High Costs (LIHC) to Low

Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE). Note A-5 explains how LILEE is calculated. In 2019 DESNZ /

BEIS produced both estimates, so both are shown on Figure A-6. The dashed line represents the

change of metric.

• On Figure A-7 the black vertical line represents the average fuel poverty gap for all households in fuel

poverty. Only households living in a dwelling with an FPEER of band D-G (Note A-4 and Figure A-1) are

categorised as ‘Low Energy Efficiency’ and are therefore at risk of being in fuel poverty depending on the

household income.

• The average fuel poverty gap by Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) band data published by

DESNZ / BEIS combines FPEER band F & G and FPEER bands A, B & C into merged categories as

used on Figure A-7. It is not possible to produce a Rural-Urban Classification chart with separate

estimates for bands F & G.

Fuel types used for central heating

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) provides information on the energy efficiency of a

building. Since 2007, an EPC is required when a building is constructed, sold or let (Note A-11).

The ONS use information from EPCs for their Energy Efficiency of Housing publication (Note A-

12). There is a March 2023 dataset covering information on the main fuel type or method of

heating used in central heating of domestic properties.

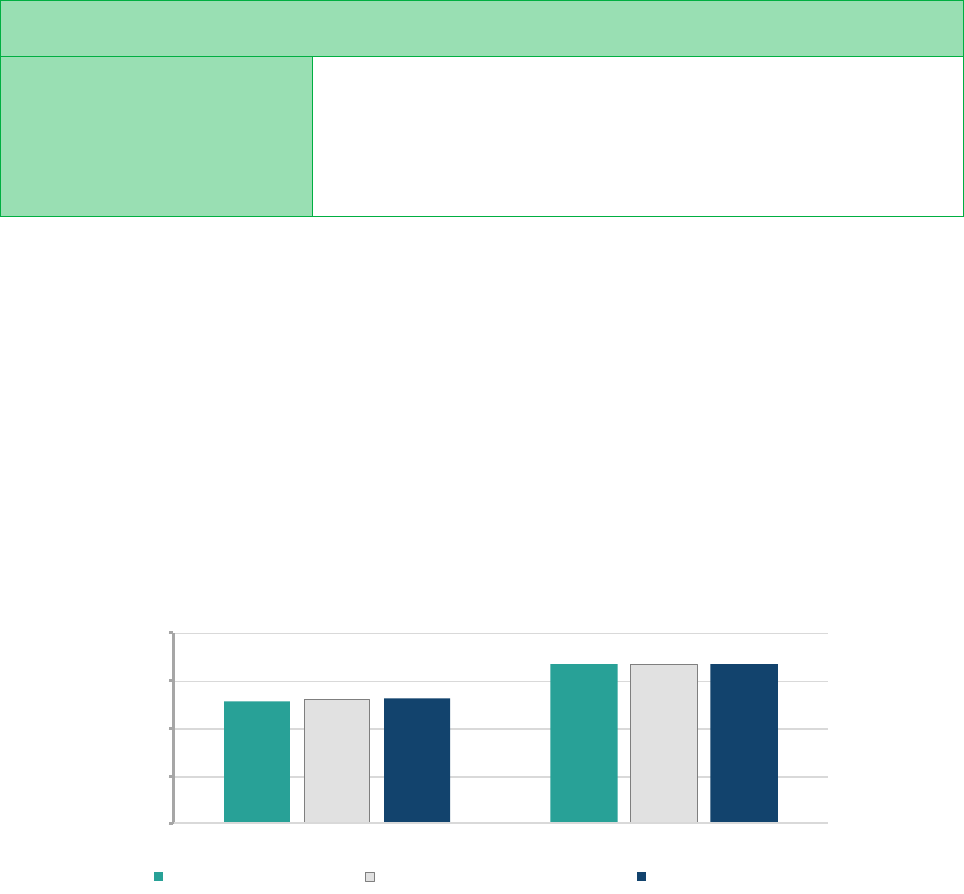

Figure A-8 shows that the most common way of heating a home was through mains gas central

heating. In Predominantly Urban areas 83% of domestic properties were using mains gas, but in

Predominantly Rural areas the proportion of homes using mains gas was only 72%. In both

Predominantly Rural and Predominantly Urban areas around 1 in 10 homes (10% in Predominantly

Rural and 11% in Predominantly Urban areas) were using electric heating. In the Annual fuel

poverty statistics report: 2024, Figure 3.9 showed that households using electricity for their heating

had the highest likelihood of fuel poverty (24.5%, compared to 11.7% for households using gas)

because of their high fuel expenditure and their lower median household income.

Figure A-8 also shows that community heating schemes were more common in Predominantly

Urban areas (5% of homes) than in Predominantly Rural areas (1% of homes). From Figure A-8, it

is clear that oil played a greater part in the heating fuel picture in Predominantly Rural areas (10%

of homes) than in Predominantly Urban areas (0.4% of homes).

As Figure A-9 shows the more Rural an area the higher the proportion of homes that used oil-

based heating systems. In Mainly Rural areas, 12% of homes were heated with oil and in Largely

Rural areas 7% of homes were heated with oil. Even in Urban with Significant Rural areas 4% of

homes had an oil-based heating system. In an Urban with Significant Rural Local Authority 26% to

49% of the population live in Rural parts of the Authority (including Rural Hub Towns). It is likely to

be the homes of these people that contribute to this 4% of homes using oil in Urban with Significant

Rural areas.

The most recent Fuel Poverty Statistics

showed that there was 166 thousand households using oil

that were fuel poor (Fuel poverty detailed tables 2024 (2023 data) - Table 13). These households

account for 5.2% of all fuel poor households and their average fuel poverty gap is £597.This is

double the average fuel poverty gap for fuel poor households who heat their home with gas.

Worksheet AD in the Energy data tables includes a Local Authority breakdown of the proportion of

properties using oil as their main fuel type. Eight Predominantly Rural Local Authorities had more

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

24

than 20% of the dwellings use oil as their main fuel type. Five of these eight where in East Anglia;

the remaining ones were Eden (which is now part of Westmorland and Furness), Rydale (which is

now part of the larger North Yorkshire Local Authority) and Torridge in Devon (Note A-16). These

data are not shown in map form because of the strong correlation with the proportion of off-grid

properties shown in Figure A-12.

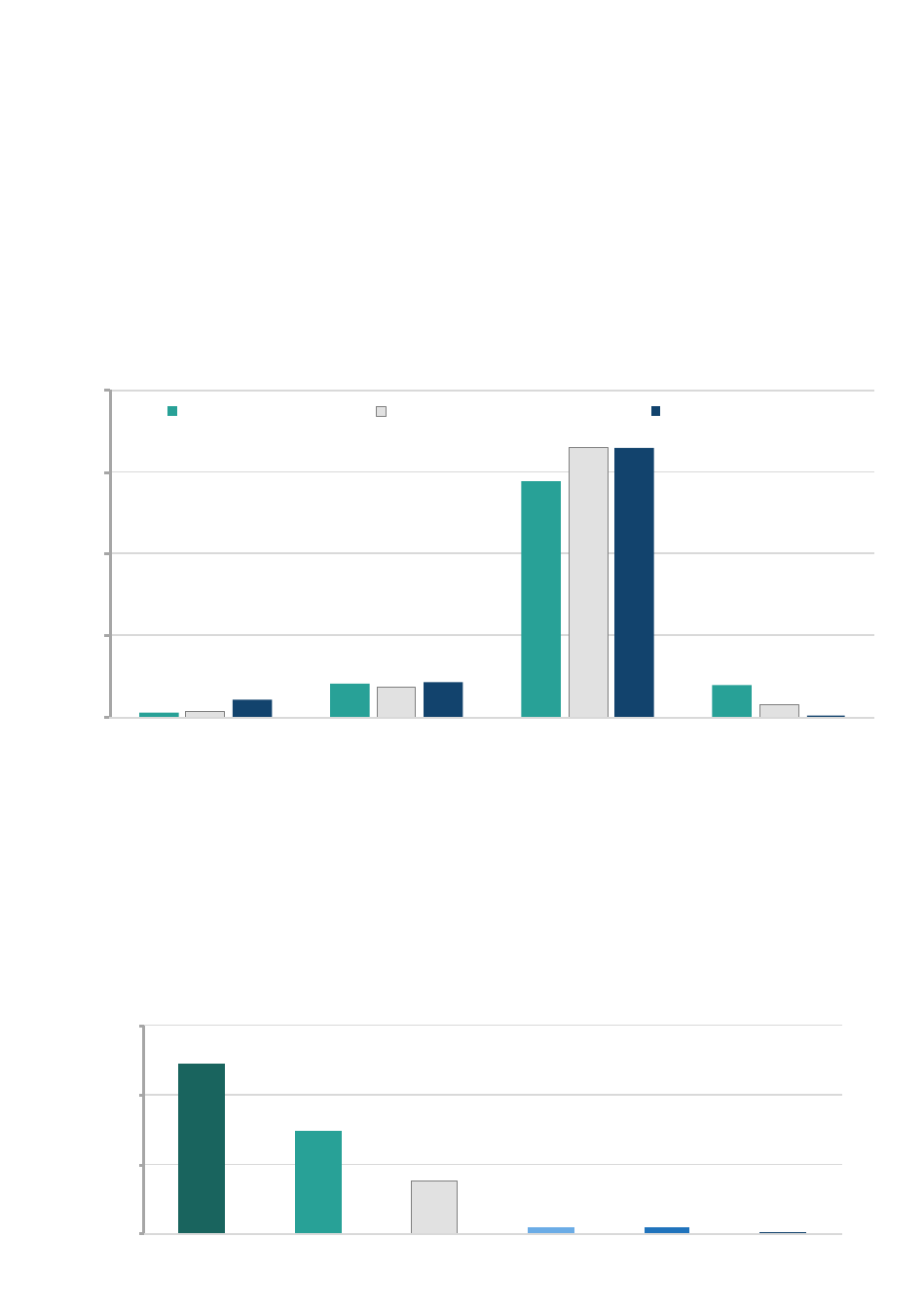

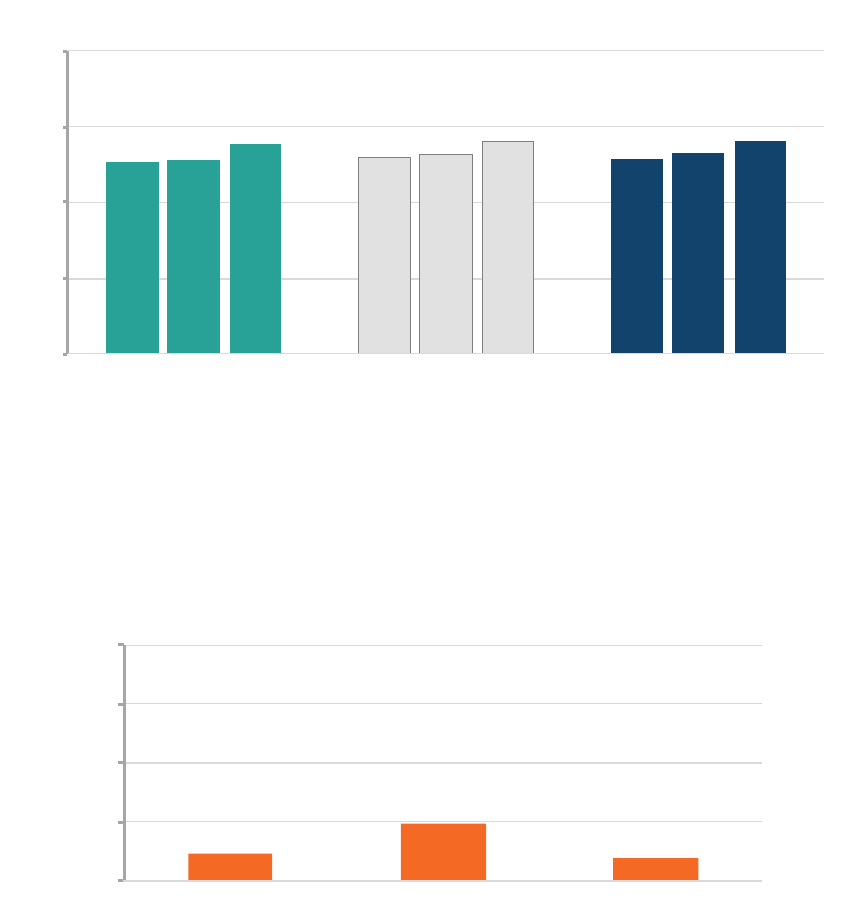

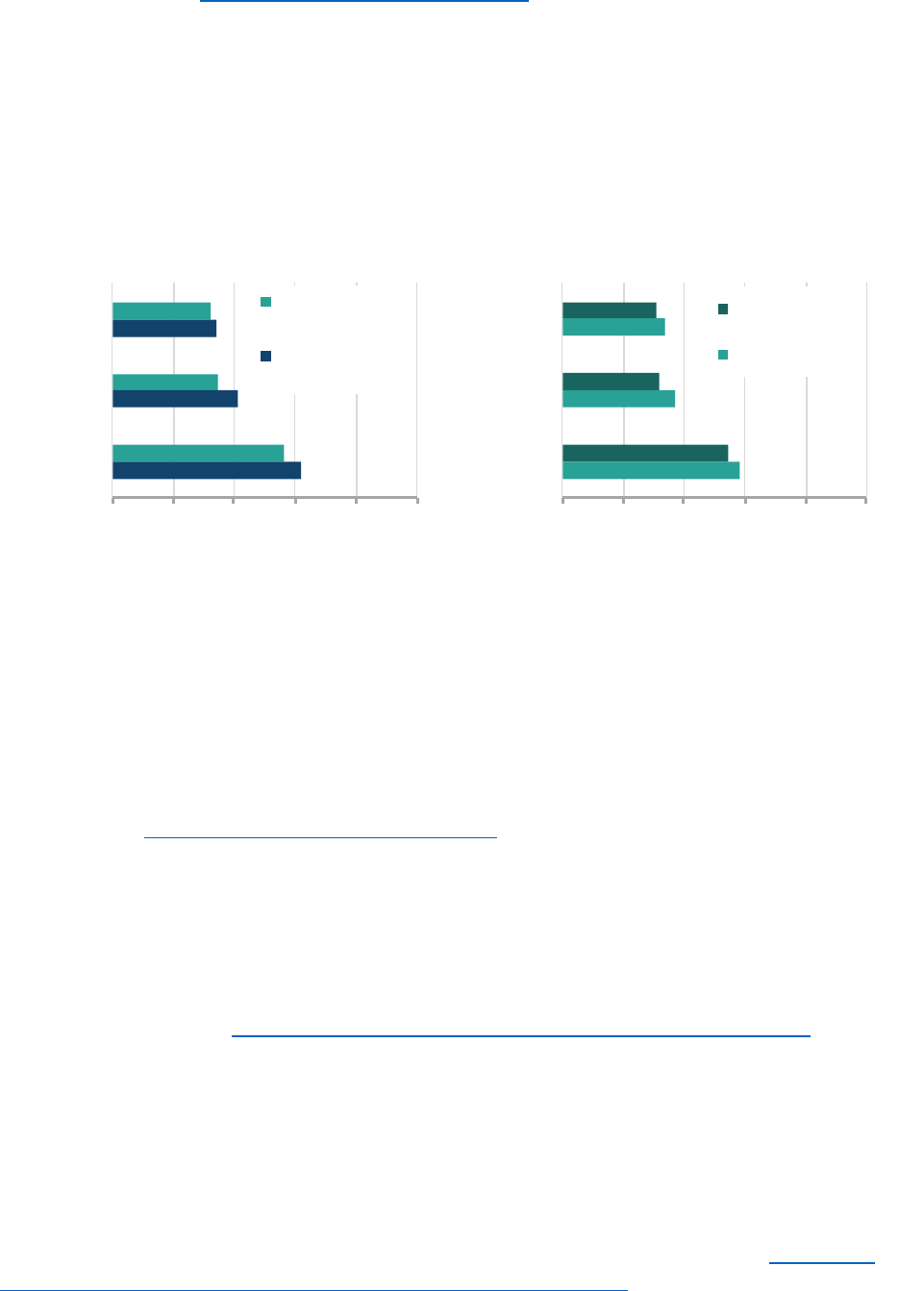

Figure A-8: Bar chart showing the percentage of domestic properties by main fuel type or

method of heating used in central heating by Local Authority Rural-Urban Classification,

2023

This analysis is based on Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) information up to March 2023.

(Note A-12, Note A-17). The legend is presented in the same order and orientation as the cluster of

columns.

Figure A-9: Bar chart showing the percentage of domestic properties using Oil fuelled

central heating by Local Authority Rural-Urban Classification, 2023

This analysis is based on Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) information up to March 2023.

(Note A-12, Note A-17).

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

Community heating

scheme

Electricity Mains gas Oil

Predominantly Rural Urban with Significant Rural Predominantly Urban

Proportion of homes

0%

5%

10%

15%

Mainly Rural Largely Rural Urban with

Significant

Rural

Urban with

City and Town

Urban with

Minor

Conurbation

Urban with

Major

Conurbation

Proportion of homes using oil

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

25

Off the gas grid properties

As explained in the previously section, not all households heat their home through central heating

with a gas boiler. In 2022 an estimated 3.7 million households did not have a gas network

connection, which is 15% of the households in England (Note A-13). In Predominantly Rural areas

one in four properties (24.5%) were off the gas grid in 2022 (Figure A-10). This compares to 11.5%

in Predominantly Urban areas. The proportion of off-grid properties in Predominantly Rural areas

had fallen by 2.4 percentage points over the period 2015 to 2022, whilst for Predominantly Urban

areas it rose by 1.6 percentage point over the same period. The value for Predominantly Rural

changed by less than 0.1 percentage points between 2021 and 2022.

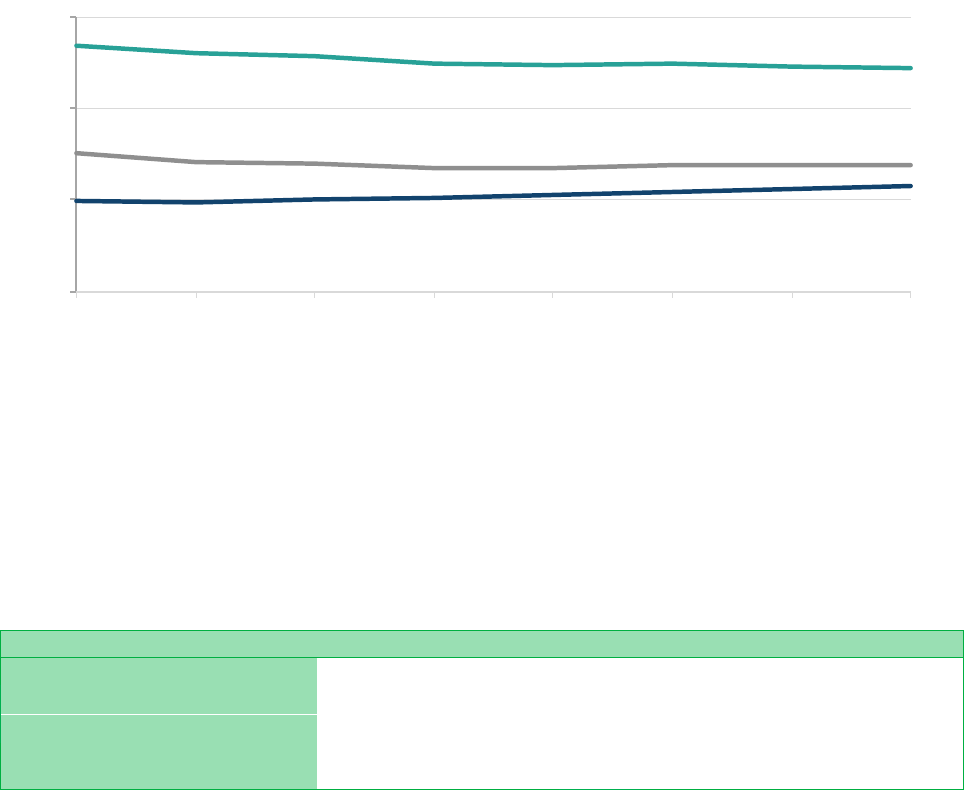

Figure A-10: Line chart showing the percentage of properties without mains gas supply by

broad Local Authority Rural-Urban Classification (2015-2022) (Note A-13)

In absolute terms, one in four properties (25%) off the gas grid means that 1.4 million properties in

Predominantly Rural areas are off the gas grid. This figure has remained stable over the period

2015 to 202 1 (Table A-1). So, the fall in the proportion of off the grid properties in Predominantly

Rural areas is probably because the vast majority of new builds are built within the “larger rural

settlements” and come with a gas connection as part of the construction process.

Table A-1: Estimated number (in millions) of properties off the gas grid in England (2015 to

2022) by Local Authority Rural-Urban Classification (Note A-13)

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Predominantly Rural

1.43

1.39

1.39

1.36

1.36

1.39

1.38

1.39

Urban with Significant Rural

0.46

0.44

0.44

0.43

0.44

0.45

0.45

0.46

Predominantly Urban

1.50

1.50

1.56

1.59

1.65

1.73

1.79

1.86

England 3.39 3.34 3.39 3.38 3.45 3.57 3.62 3.71

When DESNZ produced the latest subnational estimates of domestic properties not on the gas grid

(Note A-13), unfortunately for our purpose, these new data were produced using the 2023

boundaries (Note A-16) and values were recalculated for all years back to 2015. Note A-16

explains the local authorities that were merged to form ‘Cumberland’, ‘Westmorland and Furness’

and ‘North Yorkshire’

. As shown in Figure A-11 these have become three very large geographical

areas. The former authorities than compose Westmorland and Furness’ and ‘North Yorkshire’ had

quite different proportions of off-grid properties and not all of them were Predominantly Rural.

Merging the areas results in a loss of detail as to where off-grid properties are. For example, for the

0%

10%

20%

30%

2015

2016 2017 2018

2019 2020 2021 2022

Predominantly Rural

Urban

with Significant Rural

Predominantly Urban

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

26

new ‘Westmorland and Furness’ area in 2021 the proportion of off-grid properties in Mainly Rural

‘Eden’ and ‘South Lakeland’ was 57% and 22% respectively, but in Urban with Significant Rural

‘Barrow-in-Furness’ it was only 3% average. So, when these areas are merged together as the

Largely Rural ‘Westmorland and Furness’ the proportion of off-grid properties for 2021 became

25%. Given that the proportion of off-grid properties is not likely to change dramatically we have

decided to retain (and describe) a full map of 2021 data (Figure A-12) with its extra detail instead of

presenting a map for 2022 according to the revised boundaries. However, the 2022 data can be

found in the Energy data tables

.

Figure A-11: Map of the proportion of properties in Predominantly Rural areas of England

that are not on the gas grid in 2022 using the 2023 Local Authority boundaries (Note A-13,

Note A-16)

Local Authorities classed as Predominantly Urban or Urban with Significant Rural are shown as

white areas on the map. The 3 newly created authorities have been labelled on the map as follows:

C = Cumberland; W F = Westmorland and Furness; and N Y = North Yorkshire.

In 2021, there were three Predominantly Rural Local Authorities (Isles of Scilly, Eden, and Mid-

Suffolk) where it is estimated that at least half of the domestic properties were not on the gas grid –

see Figure A-12. A quarter of Predominantly Rural Local Authorities had at least 35% of domestic

properties off the gas grid in 2021. Most of the Local Authorities with a high proportion (greater

than 40%) of off the grid properties were located in three clusters: (1) much of Norfolk and parts of

Suffolk in the East of England; (2) Devon and Cornwall in the South West; and (3) a band in

northern England stretching from Penrith and the North Lakes south eastwards through the

Yorkshire Dales National Park and down to the North York Moors National Park (Figure A-12). For

comparison, West Berkshire was the only Urban with Significant Rural Local Authority where more

than 30% of domestic properties were off the gas grid in 2021.

A Predominantly Urban Local Authority means a Local Authority in which at least 75% of the

resident population live in Urban areas. So, it is likely that most of the domestic off the gas grid

properties within Predominantly Urban Local Authorities who are using fuels like oil and LPG are

within the “rural portion” of these authorities. However, there are also likely to be some properties

© Crown Copyright and database rights 2024

Ordn

ance Survey Licence No. 1000228

61

Proportion of properties not on

the gas g

rid in

Rural areas

Less than 10%

10% or more, but less than 25%

25% or more, but less than 40%

40% or more

Urban areas

N Y

W F

C

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

27

in Predominantly Urban areas, especially flats and apartments, that are using modern and efficient

electric heating systems and are therefore not on the gas grid. As an example, the Manchester and

Salford areas have just over 20% of their properties off the gas grid, but this is because 25% and

29% of their properties respectively are heated by electricity not gas (Table AD2,

Energy data

tables). Since the off the gas grid estimates are more ambiguous for Predominantly Urban areas,

we have opted not to display them on a map.

Figure A-12: Map of the proportion of properties in Predominantly Rural areas that are not

on the gas grid in 2021 (Note A-13)

The locations of the 3 Predominantly Rural authorities with highest proportions of off the gas grid

properties are shown as annotations. Local Authorities classed as Predominantly Urban or Urban

with Significant Rural are shown as white areas on the map. This map uses Local Authorities prior

to the reorganisation in April 2023 (Note A-16). This map has not been revised in the 2024 update.

P r o p o r t i o n o f p r o p e r t i e s n o t

o n t h e g a s g r i d i n R u r a l a r e a s

L e s s t h a n 1 0 %

1 0 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 2 5 %

2 5 % o r m o r e , b u t l e s s t h a n 4 0 %

4 0 % o r m

o r

e

U r b a n a r e a s

I s l e s o f S c i l l y

1 0 0 %

E d e n

5 7 %

M i d - S u f f o l k

5 3 %

C r o w n C o p y r i g h t a n d d a t a b a s e r i g h t s 2 0 2 3

O r d n a n

c

e

S

u r v e y L i c

e

n c e N o . 1 0

0

0 2 2 8 6 1

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

28

In the DESNZ 2023 Fuel Poverty Statistics

publication, there is a set of long-term fuel poverty trend

tables. These have been back calculated to 2010 using the LILEE approach (Note A-8). One of

these tables considers fuel poverty according to whether or not the property is connected to the

gas grid.

Back in 2010 the proportion of fuel poor households was similar for on-grid (22%) and off-grid

(23%) properties. As Figure A-12 shows the proportion of on-grid households that are fuel poor has

declined at a much faster rate the proportion of off-grid households who are fuel poor. In fact, in

recent years the proportion of off-grid households that are fuel poor has been rising after falling to

18% in 2018 and 2019. In 2023, 20% of off-grid households were fuel poor compared to only 12%

of on-grid households.

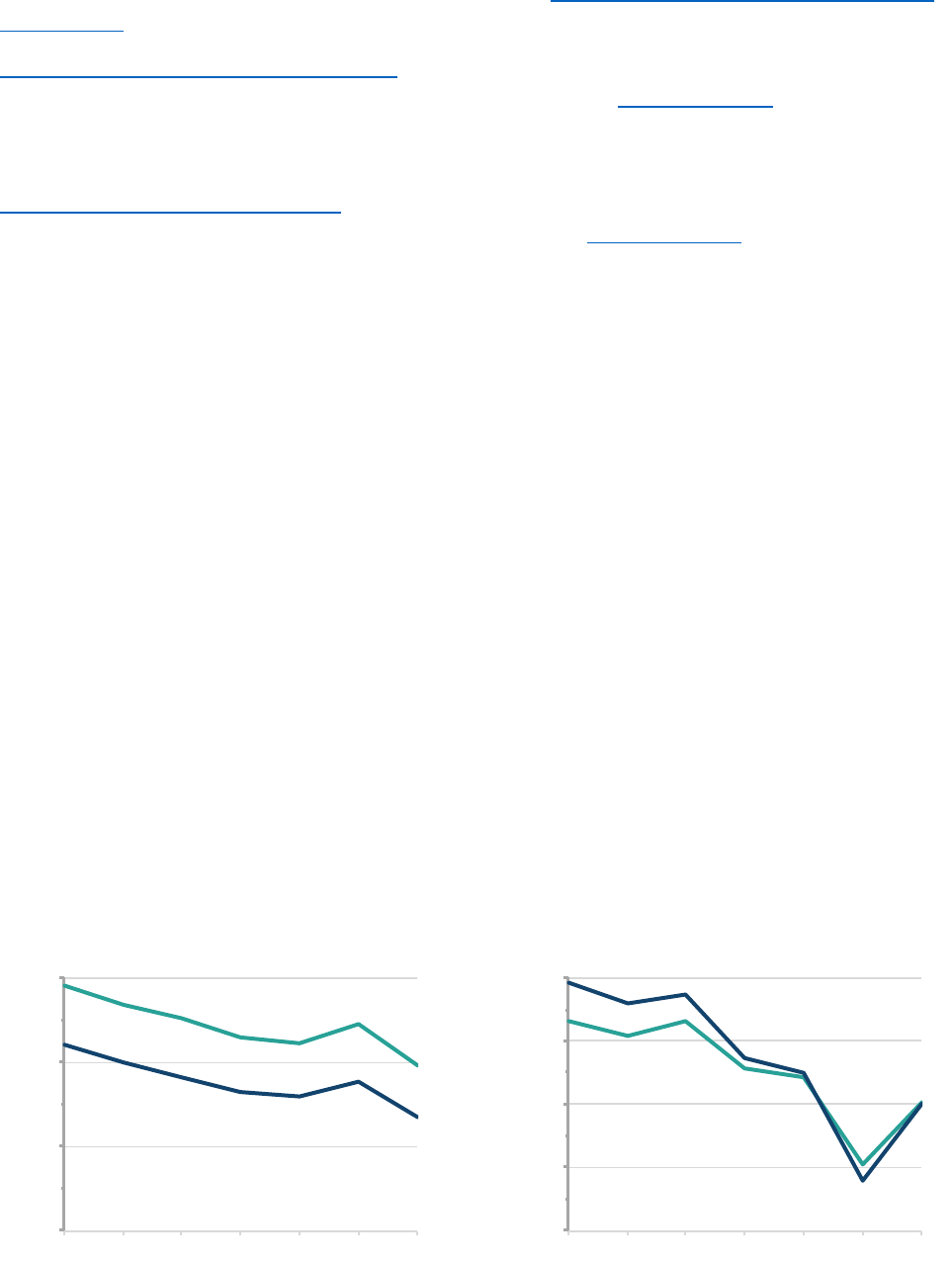

Figure A-13: Line chart showing the proportion of on and off-grid households that are fuel

poor (2011 to 2023)

All figures are based on the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) approach (Note A-8).

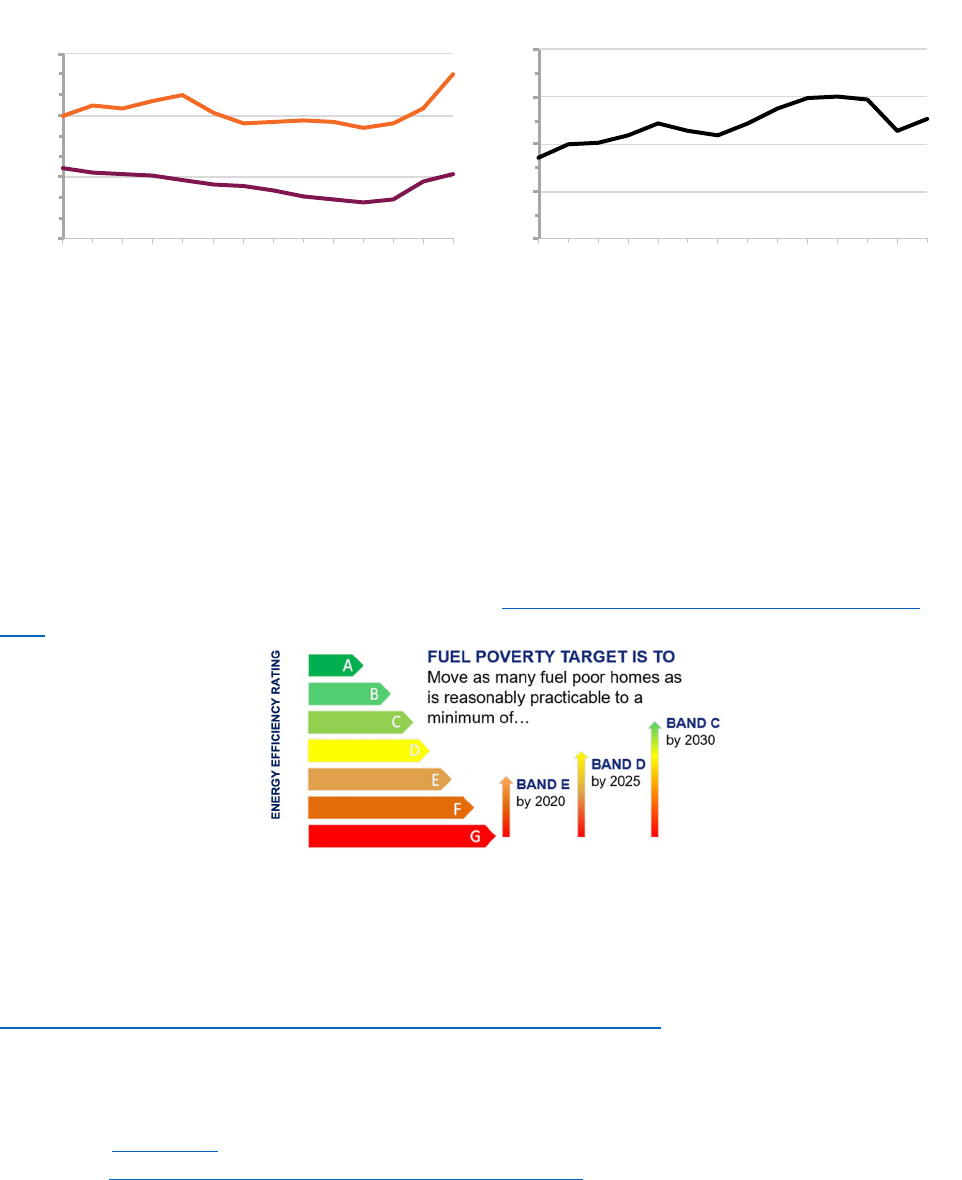

As well as there being a greater proportion of off-grid households who are fuel poor, the depth of

the fuel poverty for those who are fuel poor is also greater when the household is off the grid rather

than on it (Figure A-14 – left-hand chart). Back in 2010 the average fuel poverty gap in real terms

(after accounting for inflation, Note A-8) was £346 for on-grid properties and £598 for off-grid

properties. As Figure C 11 (left-hand chart) shows the average fuel poverty gap for on-grid

properties dropped year-on-year every year between 2010 and 2020 before rising between 2021

and 2023. By contrast for off-grid properties the average fuel poverty rose during the first part of

the 2010s hitting £700 in 2014, before falling to £536 in 2020. In the last 2 years there has been a

dramatic increase in the average fuel poverty gap for off-grid households, with the figure rising to

£629 in 2022 and then to £801 in in 2023. For off-grid households the average fuel poverty gap

rose by £172 between 2022 and 2023, but for on-grid households the rise in the average fuel

poverty gap was only £38.

A fuel poverty depth ratio can be calculated between the average fuel poverty gap for two related

categories such as off and on-grid properties. Figure A-14 (right-hand chart) shows that in 2010 the

average fuel poverty for those who are fuel poor was 1.7 times deeper for off the grid households

than for those on the grid. This disparity has grown since 2010. Even before the 2022/2023 cost of

living crisis the depth of fuel poverty amongst off-grid households was 3 times that of on-grid

households over the period 2019 to 2021. Currently fuel poverty is 2.5 times deeper for off the grid

properties that for those on the grid.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022 2024

Off grid

On grid

Proportion of households that are fuel poor

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

29

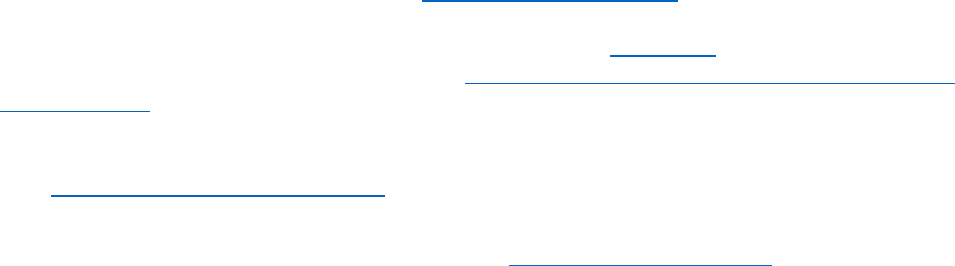

Figure A-14: Line charts showing the average fuel poverty gap for those on and off-grid

households that are fuel poor (2011 to 2023) and a comparison of the depth of fuel poverty

in on and off-grid areas

The left-hand chart shows the average fuel poverty gap (£) for those on and off-grid households

that are fuel poor. This average fuel poverty gap is in ‘real terms’. The right-hand chart shows fuel

poverty depth ratio by comparing the average fuel poverty gaps from the left-hand chart. All figures

are based on the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) approach (Note A-8).

Fuel Poverty explanatory notes

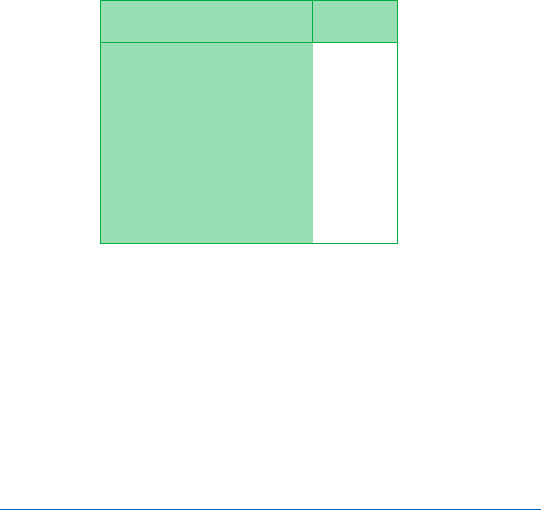

• Note A-1

The statutory fuel poverty target was set in December 2014, binding successive Governments to the

following:

The fuel poverty target is to ensure that as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably

practicable achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating of Band C, by 2030.

This target was retained in Sustainable Warmth, the updated Fuel Poverty Strategy for England, published in

February 2021. This figure taken directly from the latest

Fuel Poverty statistics released on 28 February

2023 shows the 2030 target and the intermediate targets.

• Note A-2

The ‘Low Income High Costs’ (LIHC) defined a household as fuel poor if: (a) the amount they would need to

spend to keep their home at “an adequate standard of warmth” is above the national median level and (b) if

they spent that amount, their leftover income would be below the official poverty line. LIHC was the first

measure to introduce the concept of the fuel poverty gap. More information on LIHC can be found in the

Fuel poverty methodology handbook 2020: Low Income High Costs (LIHC)

(originally published by BEIS).

• Note A-3

Traditionally there has been a lag in the publication of the Fuel Poverty statics such that the publication came

more than a year after the data collection. For example, the data relating to Fuel Poverty in 2019 was

published in March 2021

.

In the latest Fuel Poverty statistics released on 15 February 2024, DESNZ gave headline figures as

projections for 2022. They are designed to represent the period between April 2022 and March 2024

inclusive. This is a significant change made for the 2023 annual report to provide more timely estimates of

£0

£300

£600

£900

2010 2013 2016 2019 2022

Off grid

On grid

Average fuel poverty gap

(£

)

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

2010 2013

2016 2019 2022

Fuel poverty depth ratio

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

30

fuel poverty in detail. The 2023 projection is considered to be less uncertain than the 2024 projection since it

is based more on observed changes to energy efficiency installations, income changes and announced

energy prices.

• Note A-4

The Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) uses a modified version of the standard Energy

Efficiency Rating which takes into account policies that directly affect the cost of energy. In recent years this

has included the rebate provided by Warm Home Discount. The FPEER methodology deducts such rebates

from the overall modelled costs produced under the SAP system. The FPEER methodology generates a

rating between 1 and 100, which is then translated into an energy efficiency Band from G (lowest) to A

(highest) as follows:

Fuel poverty Energy

Efficiency Rating

Band

1 to 20

G

21 to 38

F

39 to 54

E

55 to 68

D

69 to 80

C

81 to 91

B

92 +

A

Note that the RPEER methodology rating will be higher than the standard rating if the household receives

additional support. The standard rating methodology is used in the Energy Performance Certificates sections

of this report (Sections B and C).

• Note A-5

Fuel poverty in England is currently measured using the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE)

methodology. According to this methodology a household is fuel poor if:

o it is living in a property with an energy efficiency rating of band D, E, F or G as determined by the

most up-to-date Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) Methodology

- this is depicted by

the horizontal threshold in Figure A-1; and

o its disposable income (income after housing costs (AHC) and energy costs) would be below the

poverty line as depicted by the vertical sloping threshold in Figure A-1.

There are therefore three key elements (drivers) in determining whether a household is fuel poor: (1)

household income; (2) household energy efficiency; and (3) fuel prices. Increased energy efficiency, higher

incomes and lower energy prices would each have a positive impact on a fuel poor household. The LILEE

fuel poverty indicator sets an absolute energy efficiency threshold making it easier to identify the impact of

changes in energy efficiency. The relative nature of the income threshold means it is harder to see the

impact of changes in income and the contribution of prices since this requires an assessment of how

household incomes and fuel costs change relative to the median income.

It is important to note that LILEE is not based on actual fuel costs. The Government is interested in the

amount of energy households need to consume to have a warm, well-lit home, with hot water for everyday

use, and the running of appliances. Fuel poverty is therefore measured based on required fuel costs of the

energy efficiency of the home rather than actual spending. An equivalisation factor is applied to reflect the

different levels of energy required depending on the number of people living in the property.

The Income element of LILEE is defined as equivalised income after housing costs, tax and National

Insurance. Equivalisation reflects that households have different spending requirements depending on the

number and age of people living in the property.

Under the LILEE indicator there is no exact point on the income axis, for a given FPEER rating, where the

household would be classed as Low Income since this threshold is measured using income minus fuel costs.

The sloping dashed line Figure A-1 marks a line of best fit between households classed as Low Income and

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

31

High Income and shows the impact of higher fuel costs in Low Energy Efficiency households. The variation

in fuel costs for a given FPEER is due to factors including property size, household size, occupancy pattern.

The depth of fuel poverty is measured by the fuel poverty gap. The fuel poverty gap is the reduction in fuel

costs needed for a household to not be in fuel poverty. This is either the change in required fuel costs

associated with increasing the energy efficiency of a fuel poor household to a Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency

Rating (FPEER) of at least 69 (band C threshold) or reducing the costs sufficiently to meet the income

threshold.

More information on the Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating (FPEER) and Low Income Low Energy

Efficiency (LILEE) can be found in the Fuel Poverty Methodology Handbook

(originally published by BEIS).

• Note A-6

An analysis of housing stock by property age and type can be found in

Statistical Digest of Rural England:2 –

Housing.

This report contains information on the number and proportion of pre-1919 houses in rural and urban areas

as well as the number of (mid and end) terraced properties. This analysis is based on the English Housing

Survey (EHS) which does not define rurality according to the RUC, it uses a looser definition based on an in-

situ assessment (see the Husing report for more details). Therefore, where this data source has been used

in this section, we refer to rural and urban instead of Rural and Urban to denote that these are not using the

strict RUC definition.

• Note A-7

Energy Saving Trust blog March 2019: Why outside the grid does not mean outside of help

.

• Note A-8

After switching to the LILEE methodology DESNZ / BEIS back calculated fuel poverty figures to 2010 using

the LILEE approach to generate a consistent time series for a selection of variables. These

long-term fuel

poverty trend tables are updated annually as part of the Fuel Poverty Statistics publication. Table 5 of the

long-term trends publication contains a breakdown for properties on and off the gas grid. In this document all

the estimates of the fuel poverty gap are in ‘real terms’, which means that they take account of inflation. These

estimates were produced by DESNZ using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflators consistent with the

Office for Budget Responsibility estimates November 2023.

• Note A-9

Annual fuel poverty statistics report 2024 (2022 and 2023 data)

sections 3.1.2 to 3.1.5 cover fuel poverty by

wall type, dwelling type, floor area and property age.

• Note A-10

Fuel poverty source data: DESNZ fuel poverty statistics:

www.gov.uk/government/collections/fuel-poverty-

statistics

• Note A-11

Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) are described in more detail in Section B Energy Performance

Certificates: average Energy Efficiency Score and Section C Energy Performance Certificates: achieving

energy efficiency category C.

• Note A-12

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publish Energy Efficiency of Housing at Local Authority level on an

annual basis for financial years. This section uses data for the financial year ending March 2023.

The source data for this ONS publication is Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities – Energy

Performance Certificate data on Open Data Communities and Valuation Office Agency - Property Attributes

data (https://epc.opendatacommunities.org/

).

There was 22 Local Authorities where the proportion of properties using oil was supressed in the source data

and they were therefore excluded from our analysis. All of them were Predominantly Urban Local Authorities

and the Local Authorities excluded can be determined from worksheet AD in the Energy data tables

.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

32

• Note A-13

DESNZ produce subnational estimates of domestic properties not on the gas grid, Great Britain. In their latest

publication the data is for 2015 – 2022 (

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sub-national-estimates-of-

households-not-connected-to-the-gas-network). Unfortunately, for our purpose, this new data has been

produced using the 2023 boundaries (Note A-16) and recalculated for all years back to 2015. This is

unfortunate because the areas merged together in Cumbria and North Yorkshire have quite different

proportions of off grid properties and merging removes a lot of detail as to where the off-grid properties are.

• Note A-14

Tables showing the data behind Figure A-3, Figure A-6 and Figure A-7 are available in the

Energy data

tables.

• Note A-15

DESNZ produce sub-regional fuel poverty data as Experimental Statistics and their latest publication

released on 23 April 2023 was for 2021 data and uses the 2023 Local Authority boundaries. It is not

possible to update

Figure A-4 or Figure A-5 until DESNZ have published newer sub-regional level data.

The sub-regional Experimental Statistics complement the National Statistics on fuel poverty, by estimating

the number and proportion of fuel poor households at smaller geographical levels, for example, Local

Authority (LA) level. However the sub-regional statistics do not report on the average fuel poverty gap. This

latest publication is the third year that sub-regional breakdowns have been produced based on the LILEE

indicator.

They are Official Statistics, produced in compliance with the Code of Practice for Statistics

and will be

undergoing an evaluation process prior to being assessed as National Statistics.

• Note A-16

New Local Authorities came into operation in April 2023. These changes relate to 3 parts of England: (1)

North Yorkshire, (2) Cumbria and (3) Somerset. This reduced the total number of Local Authorities from 309

down to 296.

1. A new unitary authority called North Yorkshire replaced the 7 existing districts of Craven,

Hambleton, Harrogate, Richmondshire, Ryedale, Scarborough and Selby. We have provisionally

classified this single North Yorkshire UA as Predominantly Rural.

2. The 6 districts within Cumbria were abolished and replaced with 2 new unitary authorities.

Allerdale, Carlisle and Copeland have been merged to form Cumberland and Barrow-in-Furness,

Eden and South Lakeland have been merged to form Westmorland and Furness. We have

provisionally classified Cumberland and Westmorland and Furness as Predominantly Rural.

3. The districts of Mendip, Sedgemoor, Somerset West and Taunton, and South Somerset have been

merged to form a new unitary authority known as Somerset. We have provisionally classified this

single Somerset UA as Predominantly Rural.

Note that the fuel type analysis based on the Energy Efficiency of Housing

publication uses the pre April

2023 boundaries.

• Note A-17

There is no mains gas on the Scilly Isles.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

33

B. Energy Performance Certificates: average Energy

Efficiency Score

Energy efficiency of homes is improving and whether the property is a house or a flat and

the age of the property are far more important factors in determining its energy efficiency

than its level of rurality.

Summary

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) provides information on the energy efficiency of a

building. Since 2007, an EPC is required when a building is constructed, sold or let; the higher the

energy efficiency score the more efficient the building. Low Income Households can only be in fuel

poverty if the Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency Rating of their home is band D or below (an Energy

Efficiency Score less than 69).

In 2023 the average Energy Efficiency Score differed little between homes in Predominantly Rural

areas (66.8) and homes in Predominantly Urban areas (67.5). Both scores are equivalent to an

Energy Efficiency Rating (EER) band D.

On average, older dwellings have a lower average efficiency rating in both Predominantly Rural

and Predominantly Urban areas. In 2023, pre-1930 properties in Predominantly Rural areas had an

average median Energy Efficiency Score of 54.2, whilst modern homes (2012 onwards) in

Predominantly Rural areas had an average Energy Efficiency Score of 83.5. Pre-1930s properties

in Predominantly Rural areas have an average Energy Efficiency Rating one band lower than for

pre 1930s properties in Predominantly Urban areas.

In 2023 flats and maisonettes had the highest average median energy efficiency score of all

domestic property types and scored virtually the same in both Predominantly Rural (73.0) and

Predominantly Urban (72.9) areas. Flats and maisonettes had an average Energy Efficiency Rating

one band higher than terraced, detached and semi-detached properties. In Predominantly Rural

areas on average a new detached property had an Energy Efficiency Score 23 points higher than

the average for existing detached properties.

In 2023 in both Predominantly Rural and Predominantly Urban areas, in terms of tenue, the lowest

average Energy Efficiency Score was for owner occupied properties and the highest was for social

rented properties. The private rental sector had the biggest difference in average Energy Efficiency

Scores between Predominantly Rural (63.8) and Predominantly Urban areas (66.2).

Half of the Predominantly Rural Local Authorities had average Energy Efficiency Scores that were

within 1 point of the median Energy Efficiency Score of 67. Half of Predominantly Rural Local

Authorities had an average Energy Efficiency Score of 55 or less for pre-1930s properties but only

7 of 175 Predominantly Urban Local Authorities (about 5%) had an average Energy Efficiency

Score of 55 or less for pre-1930s properties.

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

34

Energy Performance Certificates and ratings

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) provides information on the energy efficiency of a

building. Since 2007, an EPC is required when a building is constructed, sold or let. The Energy

Efficiency Score shows the energy efficiency of a building at the time of its EPC assessment. The

higher the score, the more energy efficient a building is. An Energy Efficiency Rating band from A

to G can also be used to interpret this score, where A is very energy efficient, and G is very energy

inefficient (Table B-1). Households can only be in fuel poverty if the Energy Efficiency Rating of the

home, as defined by the latest Fuel Poverty Energy Efficiency methodology, is band D or below

(Note B-2, Note B-3). Note B-5 contains more details about EPCs.

Table B-1: Lookup table to aid interpretation of Interpreting energy efficiency scores

Energy Efficiency Score

Energy Efficiency Rating band

More than 91 A

81 to 91 B

69 to 80 C

55 to 68 D

39 to 54 E

21 to 38 F

1 to 20 G

This data does not reflect all dwellings in England, because not every dwelling has an EPC. Table

4a of Median energy efficiency score, England and Wales

shows the percentage of dwellings

covered by an Energy Performance Certificate since records began, in England and Wales, as at

31 March 2023. Overall, in England around two-thirds of domestic properties are covered by EPCs.

In general, the coverage is higher for:

• for newer properties (95% coverage of post 2012 properties) than older ones;

• rented properties than owner occupied; and

• flats and maisonettes (83% coverage) than houses (60% coverage for detached

properties).

Average energy efficiency

The ONS publish Energy Efficiency of Housing on an annual basis (see Note B-4 and Note B-5

).

The most recent edition was published in November 2023.

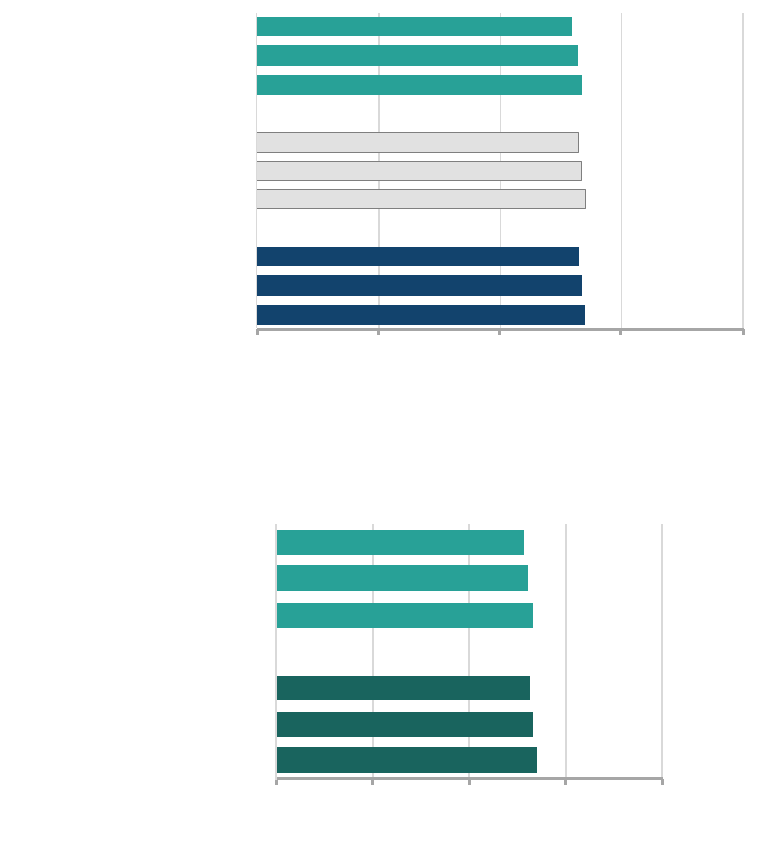

There is little difference between the average Energy Efficiency Score of homes in Predominantly

Rural areas (66.8 in 2023) and homes in Predominantly Urban areas (67.5 in 2023). In both

Predominantly Rural and Predominantly Urban areas this average Energy Efficiency Score

equates to an Energy Efficiency Rating of D. In both Predominantly Rural and Predominantly

Urban areas the average energy efficiency increased marginally year-on-year between 2021 and

2023 (Figure B-1). In Predominantly Rural areas the change has been slightly larger over this 2

year period than in Predominantly Urban areas. The average Energy Efficiency Score has

increased by 2.1 (3%) in Predominantly Rural areas and in Predominantly Urban areas it increased

by 1.3 (2%).

Homes in Mainly Rural areas have an average Energy Efficiency Rating that is slightly lower than

for homes in Largely Rural areas (Figure B-2), so the more rural an area the lower the average

Energy Efficiency Rating. The average Energy Efficiency Rating increased year-on-year between

Digest of Rural England: 8 – Energy

35

2021 and 2023 in both Mainly Rural and Largely Rural areas. This increase was marginally larger

in Largely Rural areas (3.4%) than in Mainly Rural areas (3.1%)

Considering only the average hides information because there are several factors that can

influence the Energy Efficiency Rating of homes. Two of them are the housing type and housing

age. Subsequent sections examine these two factors.

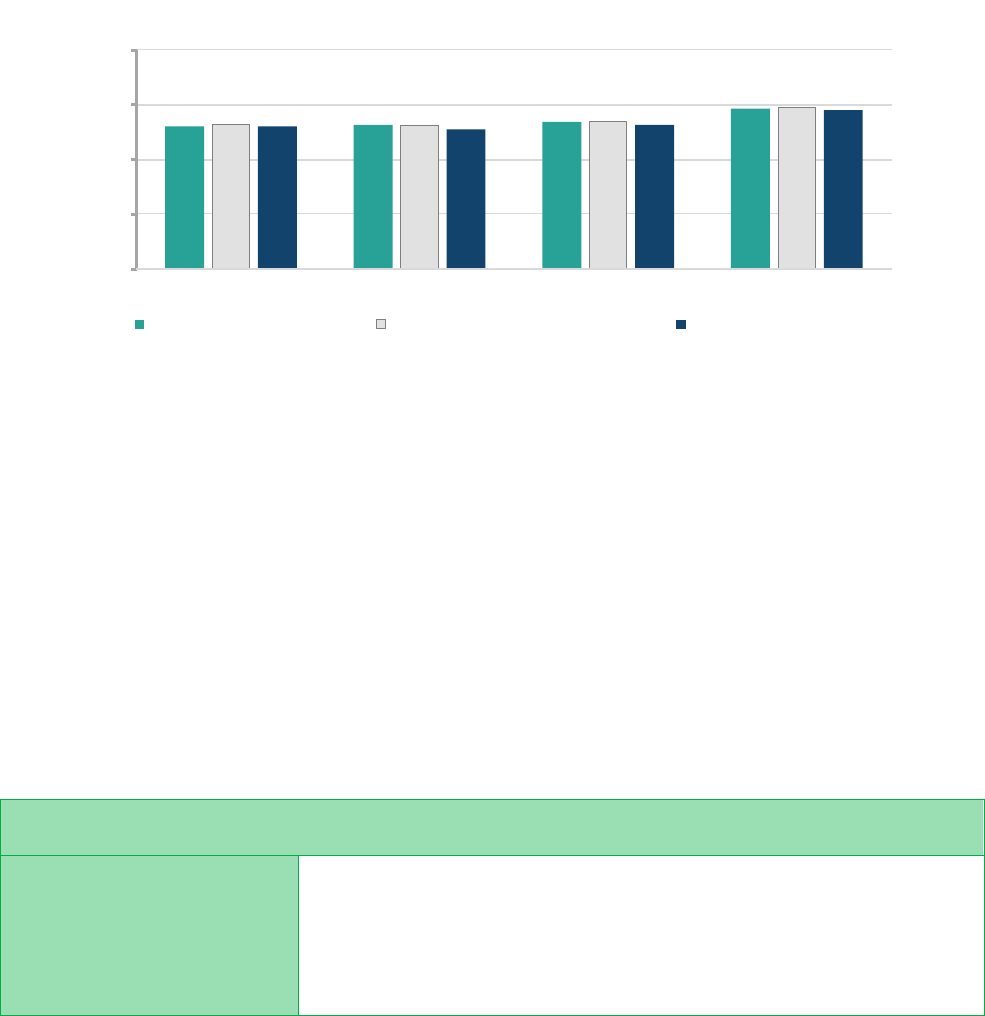

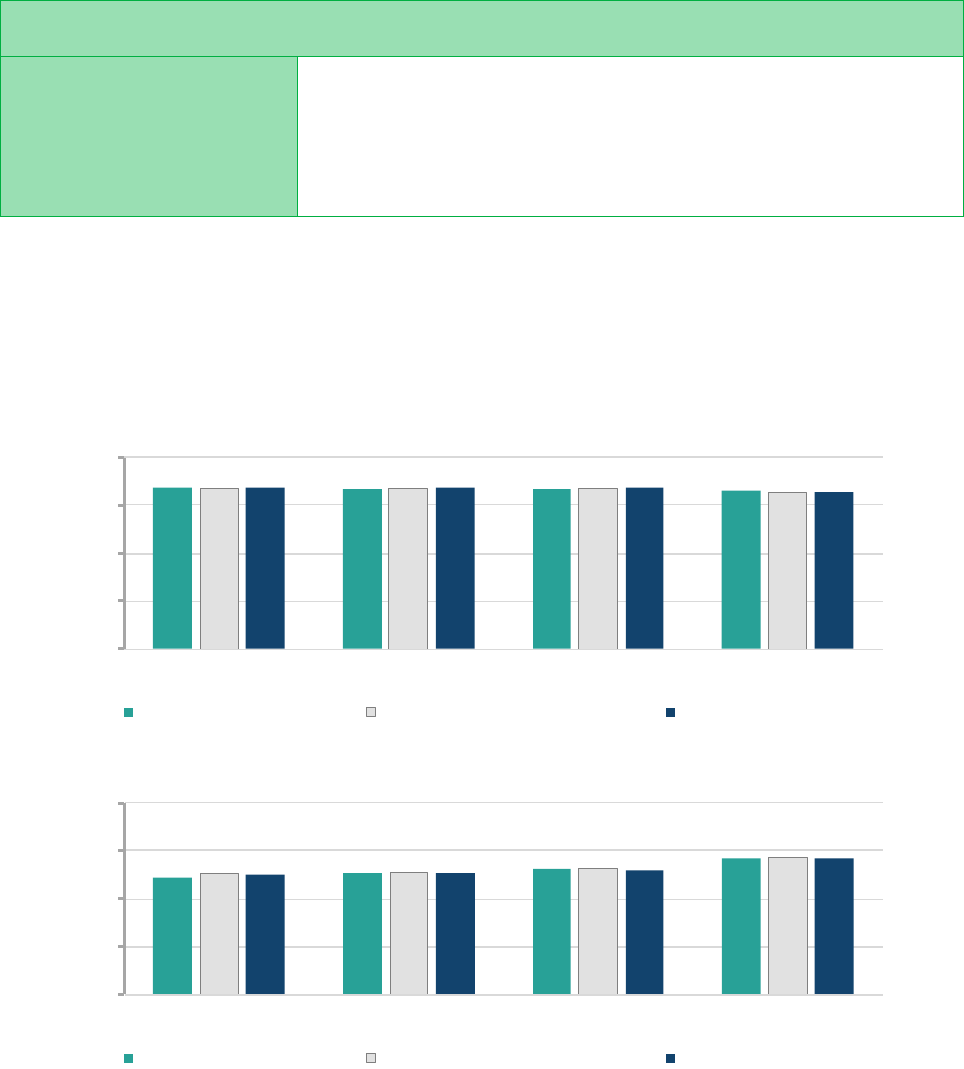

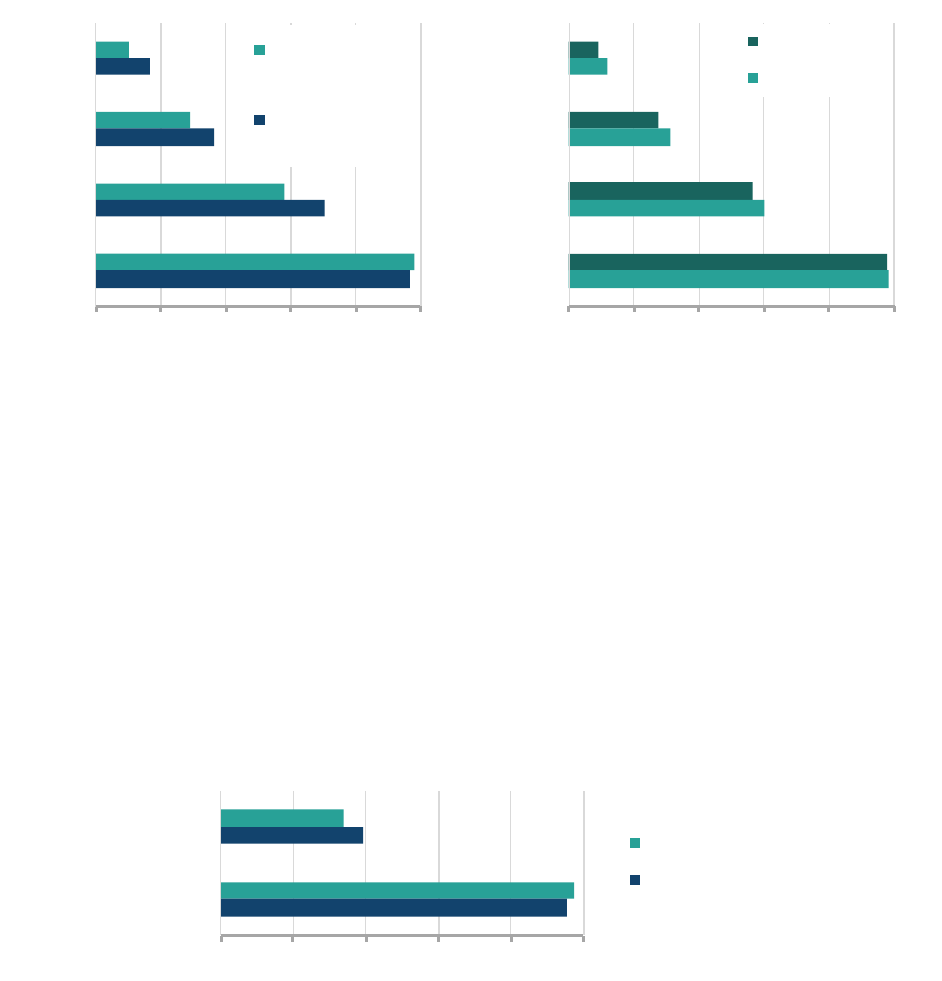

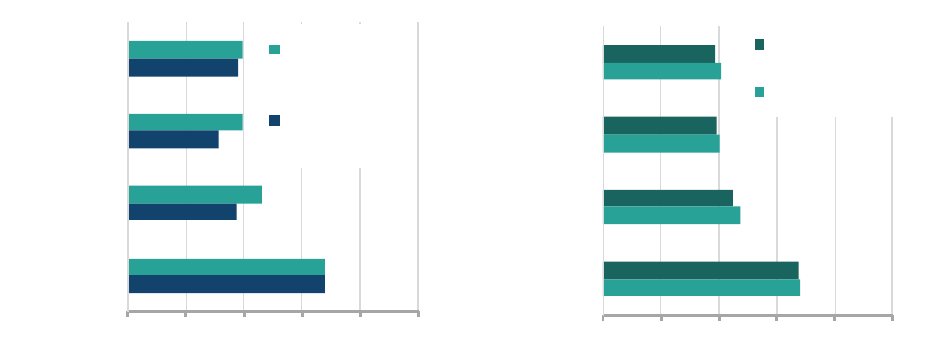

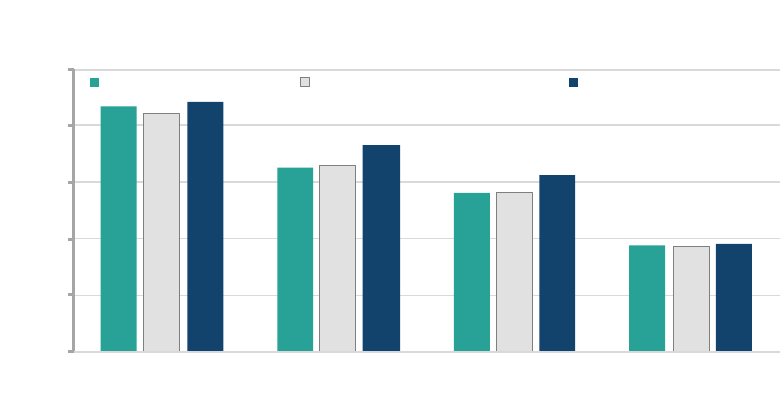

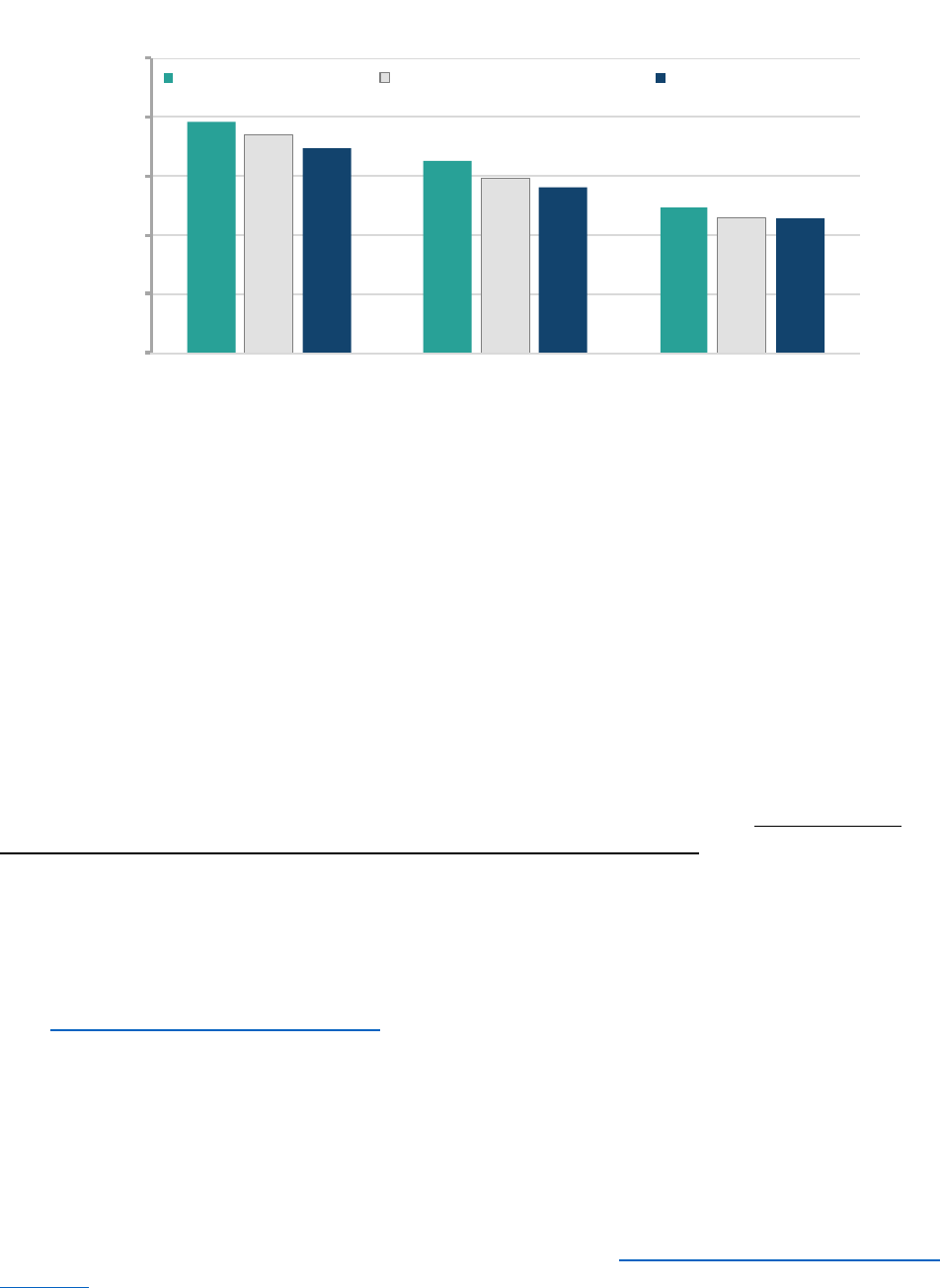

Figure B-1: Bar chart showing average Energy Efficiency Score by Local Authority Rural-

Urban Classification in 2021, 2022 and 2023 (Note B-4)

Figure B-2: Bar chart showing average Energy Efficiency Score for Rural areas by Rural-

Urban Classification in 2021, 2022 and 2023 (Note B-4)

Average energy efficiency by housing age

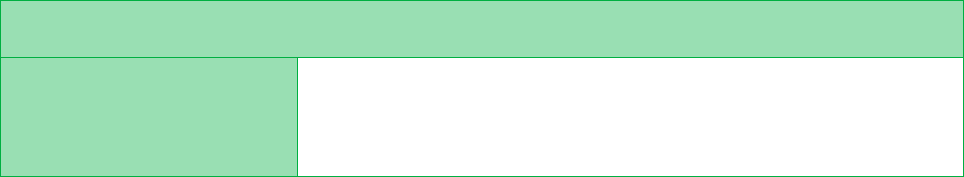

On average, older dwellings had a lower average efficiency rating in both Predominantly Rural and

Predominantly Urban areas (Figure B-3).

For pre-1930 properties in Predominantly Rural areas the average median Energy Efficiency Score

in 2023 was 54.2, which equates to an average Energy Efficiency Rating of E. For properties in

Predominantly Rural areas built between 1930 and 1982 the average Energy Efficiency Score

equated to a rating of D. For 2023 the average Energy Efficiency Score for homes built between

1983 and 2011 was just within the band for an average Energy Efficiency Rating of C and for

0 25 50

75

100

2021

2022

2023

2021

2022

2023

2021

2022

2023

Average Energy Efficiency Score

Predominantly

Rural

Urban with

Significant

Rural

Predominantly

Urban

0 25 50 75 100

Mainly Rural, 2021

Mainly Rural, 2022

Mainly Rural

, 2023

Largely Rural, 2021

Largely Rural

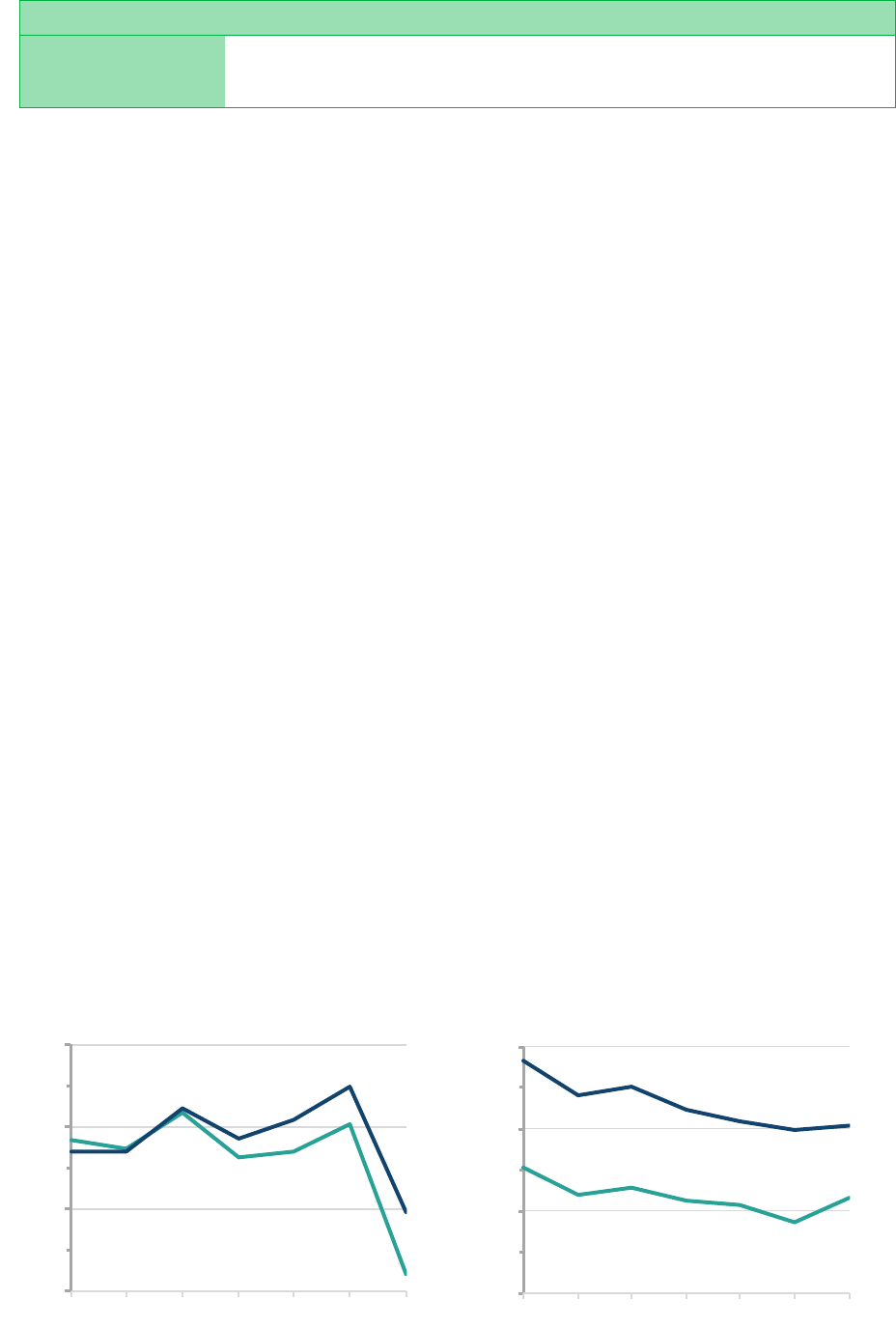

, 2022