REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 222377 (ENGLAND AND WALES)

Housing Law: Supporting

tenants with a disability

Mencap WISE Student

Advice Project

This tool kit was prepared by students from the School of

Law & Politics at Cardiff University, with supervision from

Rob Ryder (Solicitor, non-practising), and assistance from

Jason Tucker (Reader) and David Dixon (Senior Lecturer).

.

Table of Contents

Introduction ......................................................................................................... 4

I. Part 1 – The main types of tenancy ........................................................... 6

What is a tenancy?.......................................................................................................................................... 6

What is security of tenure? .......................................................................................................................... 6

Types of tenancy .............................................................................................................................................. 7

(1) Secure tenancy ...................................................................................................................................................... 8

(2) Assured tenancy .................................................................................................................................................. 10

(3) Assured shorthold tenancy .............................................................................................................................. 11

(4) Introductory tenancy ........................................................................................................................................... 12

(5) Demoted tenancy ................................................................................................................................................ 13

Glossary of key terms used in Part 1 ..................................................................................................... 14

II. Part 2 – Possession proceedings ............................................................ 16

Grounds for Possession .............................................................................................................................. 16

(1) Discretionary grounds and reasonableness ............................................................................................. 17

(2) Grounds for possession – secure tenancy ............................................................................................... 18

(3) Grounds for possession – assured tenancy ............................................................................................. 20

(4) Grounds for possession – assured shorthold tenancy ........................................................................ 23

(5) Grounds for possession – introductory and demoted

tenancies ............................................................................................................................................................................... 23

Possession Notices....................................................................................................................................... 24

(1) Notice requirements for secure and assured

tenancies ............................................................................................................................................................................... 24

(2) Notice requirements for assured shorthold tenancies ......................................................................... 24

(3) Notice requirements for introductory and demoted

tenancies ............................................................................................................................................................................... 26

(4) Rent arrears and social housing ................................................................................................................... 27

Defences to Possession Claims .............................................................................................................. 29

(1) Defective possession notice ........................................................................................................................... 29

(2) Landlord’s failure to establish grounds for possession........................................................................ 30

(3) Reasonableness .................................................................................................................................................. 30

(4) Discrimination ........................................................................................................................................................ 30

(5) Public law defences ............................................................................................................................................ 37

(6) Human Rights Act defences ........................................................................................................................... 39

(7) Claims against travellers .................................................................................................................................. 41

Alternatives to litigation ............................................................................................................................... 42

(1) Complaint about a local authority or other social

landlord .................................................................................................................................................................................. 42

(2) Complaint about a private landlord .............................................................................................................. 43

(3) The Public Services Ombudsman for Wales ........................................................................................... 43

(4) Mediation ................................................................................................................................................................. 43

Obtaining legal advice ................................................................................................................................. 44

Going to court .................................................................................................................................................. 44

Supporting a tenant threatened by eviction – a

checklist ............................................................................................................................................................. 46

III. Part 3 – Repairs and improvements ........................................................ 48

Repairs ............................................................................................................................................................... 48

(1) Private landlords .................................................................................................................................................. 48

(2) Social landlords .................................................................................................................................................... 50

Improvements ................................................................................................................................................. 51

(1) Compensation for improvements .................................................................................................................. 52

(2) Planning permission and building regulations approval ...................................................................... 54

The duty to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ ....................................................................................... 54

(1) Who is under a duty to make reasonable

adjustments? ....................................................................................................................................................................... 54

(2) What are the key obligations placed on landlords? .............................................................................. 54

(3) When does the duty to make reasonable adjustments

arise? 55

(4) Who bears the costs of a reasonable adjustment? ............................................................................... 56

(5) Disability Adaptations ........................................................................................................................................ 56

(6) Disabled Facilities Grants ................................................................................................................................ 58

IV. Part 4 – Additional resources ................................................................... 62

Citizens Advice (Wales) .............................................................................................................................. 62

Disability Rights UK ...................................................................................................................................... 62

Equality and Human Rights Commission ............................................................................................ 62

Westminster Government ........................................................................................................................... 62

Shelter Cymru ................................................................................................................................................. 62

V. Future Changes ......................................................................................... 63

Notice of Seeking Possession – Secure Tenancy

(Periodic) ........................................................................................................................................................... 64

Notice of Seeking Possession – Secure Tenancy

(Fixed-term) ...................................................................................................................................................... 67

Appendix 2 ........................................................................................................................................................ 70

Notice of Seeking Possession – Assured Tenancy ......................................................................... 70

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 4

Introduction

The law relating to rented property is covered by a wide range of statutes,

regulations and case law. Many aspects of the law are difficult to

understand. As a result of this complexity, disputes frequently arise

between landlords and tenants. This tool kit aims to simplify and explain

two important features of the legal framework:

a landlord’s right to evict a tenant; and

the respective rights and responsibilities of a landlord and tenant

regarding repairs and improvements to rented property.

This tool kit has been prepared as part of the Mencap WISE project, funded

by the Welsh Government. Therefore, it focuses on the law and procedure

applicable in Wales. As well as providing general information about the law

relating to rental property, the tool kit aims to assist people acting as

learning disability advocates (be that parent, carer, volunteer or

professional), and so particular consideration is given to the law relating to

tenants who have a disability.

The tool kit is divided into four parts:

Part 1 – The main types of tenancy – explains the legal requirements and

key characteristics of the five types of tenancy agreement featured in the

tool kit. There are many different types of tenancies, and it is beyond the

scope of the tool kit to consider all of them. Instead, the types of

agreement included are those that are most common in the social housing

and private rental sectors.

Part 2 – Possession proceedings – explains the main procedural

requirements relating to possession claims, and the defences that may be

used by a tenant when faced with the threat of eviction. It includes some

guidance regarding the relatively new defences to possession claims,

which rely on public law principles, human rights and disability

discrimination law. Part 2 also includes some practical guidance about the

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 5

steps that can be taken by a tenant (or someone acting on the tenant’s

behalf) in response to a threat of eviction.

Part 3 – Repairs and improvements – explains the respective rights and

obligations of landlords and tenants to repair and make improvements to a

rented property, and includes some guidance on grants and compensation

that may be available to a tenant to cover the cost of any works needed.

Part 4 – Additional resources – contains a list of ‘additional resources’,

including links to various organisations that publish online guidance on a

range of topics linked to the matters covered in the tool kit.

The tool kit includes hyperlinks to key online resources. Wherever a

reference is underlined in the text, it indicates that it is a hyperlink, which

will take you to the relevant external resource.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 6

Part 1 – The main types of tenancy

Understanding what type of tenancy the person you are supporting has is

very important, as different types of tenancy provide different levels of

protection for tenants. This Section will explain the key features of the five

types of tenancy that are most common in the social housing and private

rental sectors. In addition, you may find it useful to refer to Shelter's online

'tenancy rights checker', which asks a series of questions to help establish

what type of tenancy a person has.

What is a tenancy?

A tenancy is a legal contract between a tenant and a landlord. It may be

written or oral. The tenancy sets out the terms and conditions for living in

the property, as well as the obligations of the landlord and tenant.

Key Information and Resources:

The tenancy agreement

If the tenant you are supporting has not been given a copy of their

tenancy agreement, it is advisable to ask the landlord to provide one.

This will ensure that the tenant is fully aware of the terms and conditions,

and his/her rights within the tenancy agreement.

What is security of tenure?

Put simply, this is a tenant’s right to remain in the property and the

restrictions imposed by the law on the landlord’s ability to evict the tenant.

The degree of security of tenure enjoyed by tenants depends on the type of

tenancy.

Tenancies can either be granted for a fixed-term or can be periodic. A

fixed-term tenancy is granted for a set period and expires on a fixed date.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 7

A periodic tenancy does not have an end date and runs from week to week,

or month to month, depending on how the rent is calculated.

Even when the tenancy is for a fixed-term, the landlord is not automatically

entitled to possession of the property when the fixed-term expires. Once

the term expires, the tenant becomes a statutory periodic tenant. What

this means is that, when the fixed-term tenancy expires, the law deems the

tenant to have been granted a periodic tenancy on the expiry of their fixed-

term tenancy. As a result the tenant continues to have security of tenure,

and can only be evicted if the landlord obtains an order for possession from

the court.

Key Information and Resources:

Example – statutory periodic tenancy

Jane has a five year fixed-term tenancy, and her rent is calculated on a

monthly basis.

At the end of the five year term the fixed-term tenancy will cease, and

Jane will be treated as a monthly statutory periodic tenant. This means

that she will still have security of tenure, and can only be evicted if the

landlord obtains an order for possession from the court.

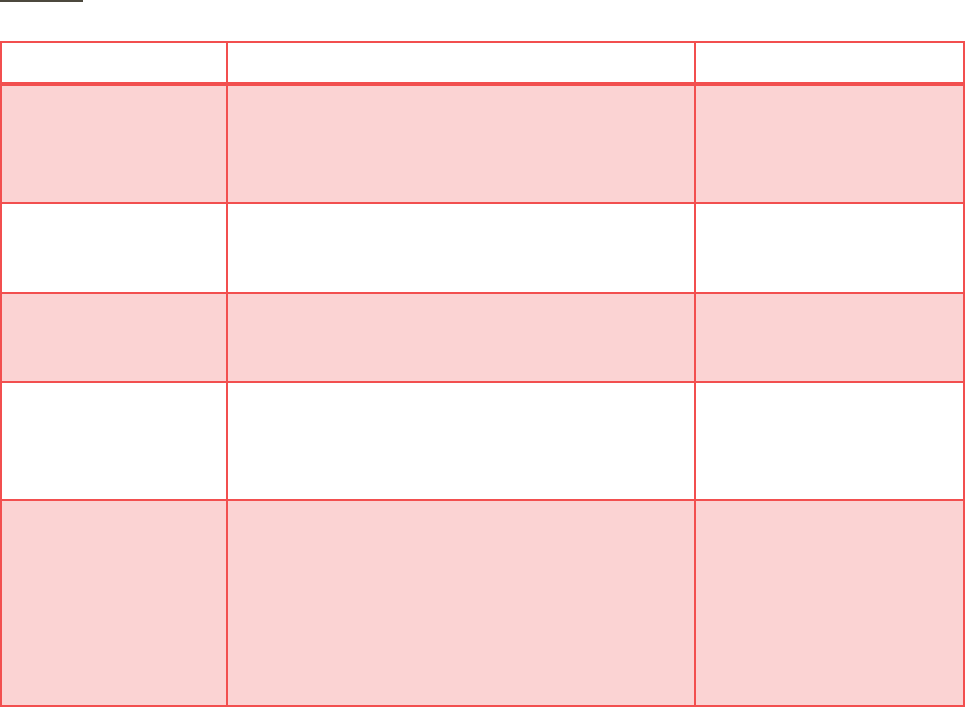

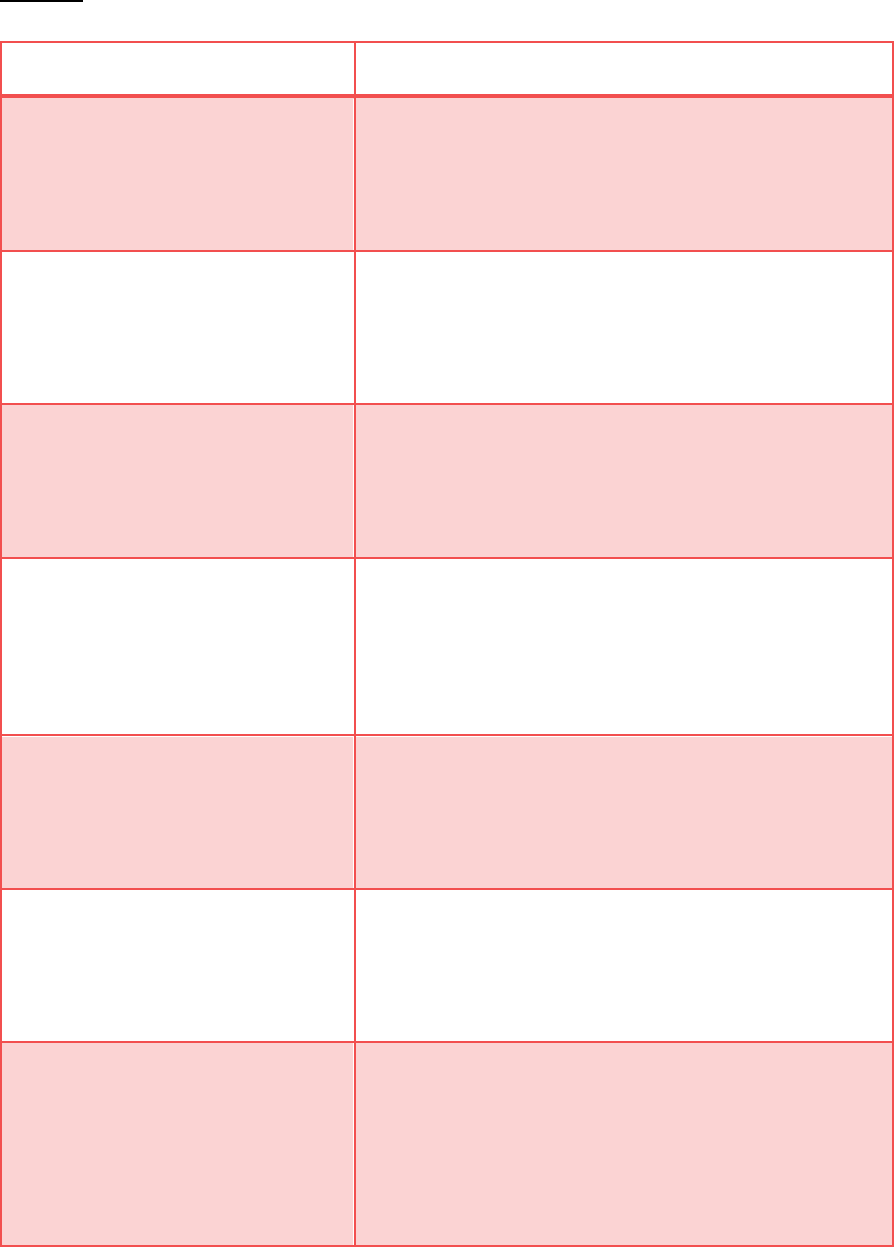

Types of tenancy

There are many types of tenancy. However, this tool kit will focus on the

most common tenancy agreements. Table 1 summarises the key

information relating to the tenancy agreements considered.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 8

Table 1: The main types of tenancy agreement.

Tenancy

Type of Landlord

Statute

Secure

Tenancies granted by Local Authorities; and

Tenancies granted by Housing Associations

before 15 January 1989.

Housing Act 1985

Assured

Tenancies granted by, for example a Housing

Association, from 15 January 1989.

Housing Act 1988

Assured Shorthold

Tenancies principally granted by private

landlords from 15 January 1989.

Housing Act 1988

Introductory

Tenancies granted by Local Authorities to

new tenants, on a probationary or trial basis,

usually for a period of 12 months.

Housing Act 1996

Demoted

Secure or assured tenancies may be

‘demoted’ by the court on the application of a

social landlord in the case of anti-social

behaviour by the tenant.

Anti-Social Behaviour

Act 2003

[amending Housing Act

1988 (for assured

tenancies) & Housing Act

1996 (for secure

tenancies)]

(1) Secure tenancy

Secure tenancies are most commonly granted by Local Authorities.

Tenancies granted by Housing Associations before 1989 are also secure

tenancies.

A secure tenant will have the right to stay in the accommodation for the rest

of the tenant’s life, provided that the tenant complies with the tenancy

agreement. Secure tenancies can only be ended by a court order. A court

order will only be made if one or more of the statutory grounds (reasons) is

established by the landlord.

Part IV Housing Act 1985 sets out the conditions for creating secure

tenancies. The conditions are:

the property is a dwelling house;

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 9

the landlord is a prescribed social landlord;

the tenant is an individual;

the tenant occupies the property as his/her only, or principal, home;

the property is let as a separate dwelling; and

the tenancy is not in an excluded category under Schedule 1Housing

Act 1985 (which excludes specific types of tenancy such as fixed

term leases over 21 years and student accommodation).

Key Information and Resources:

What is a ‘prescribed social landlord’?

Social housing is accommodation that is provided at an affordable rent.

Unlike private rental accommodation it is allocated on the basis of need.

Social housing is provided by social landlords, with the main categories

of social landlord being: local authorities, housing associations and not

for profit companies.

In Wales, social landlords (other than local authorities) have to be

registered on the register of social landlords and must manage their

accommodation in line with standards set out by the Welsh Government.

This includes having an efficient repairs and maintenance service that

responds to tenants’ needs.

A private individual cannot be a social landlord, and this means that a

secure tenancy cannot be granted by a private landlord.

The most important feature of a secure tenancy is the security of tenure

that it gives the tenant, as s82 Housing Act 1985 provides that a secure

tenancy can only be ended, by a landlord, if the landlord obtains a

possession order from the court. A possession order can only be made if

one of the grounds under s84 Housing Act 1985 is established (and the

grounds are discussed in Grounds for Possession - (2) secure tenancy).

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 10

In addition, a secure tenant has the right to pass the tenancy to his/her

partner, or to a family member, upon the tenant’s death (this is sometimes

referred to as the ‘right to succession’).

The third protection which secure tenants have is that they can enforce

their rights without worrying about being evicted, including the rights to:

have certain repairs carried out by the landlord;

carry out certain repairs and to do improvements themselves;

sublet part of the tenant’s home with the landlord’s permission;

take in lodgers without the landlord’s permission;

exchange the tenant’s home with certain other social housing

tenants;

vote to transfer to another landlord (if the landlord is a local authority);

be kept informed about matters relating to the tenant’s tenancy;

buy the home.

Additionally, secure tenants have the right not to be treated unfairly by the

landlord because of disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and

maternity, race, religion or belief, sex or sexuality.

(2) Assured tenancy

Assured tenancies are generally those offered by housing associations

from 15 January 1989, following the enactment of the Housing Act 1988.

This type of tenancy is similar to a secure tenancy, but assured tenants do

not enjoy a ‘right to buy’, although they may have a ‘right to acquire’ the

property. In addition, the grounds for possession are different.

Section 1 Housing Act 1988 sets out the conditions for creating assured

tenancies. The conditions are as follows:

the tenancy must be of a dwelling house “let as a separate dwelling”;

the tenant must be an individual, and if there are joint tenants all must

be individuals;

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 11

the tenant (or tenants if they occupy the property jointly) must occupy

the property as his/her only, or principal, home; and

the tenancy is not in an excluded category under Schedule 1Housing

Act 1988 (which excludes specific types of tenancy such as fixed

term leases over 21 years and student accommodation).

The protection that an assured tenant has is very similar to that enjoyed by

a secure tenant, with the most important feature being the tenant’s long-

term security of tenure. Under s5 Housing Act 1988, an assured tenancy

can only be ended by the landlord, if the landlord obtains a possession

order from the court. A possession order can only be made if one of the

grounds under Sch 2 Housing Act 1988 is established (and the grounds

are discussed in Grounds for Possession - (3) assured tenancy).

In addition, assured tenants have the right to enforce their rights under the

tenancy agreement without worrying about getting evicted. As well as the

right to stay in the home, so long as the tenant keeps to the terms of the

tenancy, the tenant will also have the right to:

have the accommodation kept in a reasonable state of repair; and

carry out minor repairs themselves and to receive payment for these

from the landlord.

As with secure tenants, assured tenants have the right to pass the tenancy

to his/her partner (or to a family member) upon the tenant’s death, and the

right not to be treated unfairly by the landlord because of disability, gender

reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex or

sexuality.

(3) Assured shorthold tenancy

Assured shorthold tenancies are the most common type of tenancy

agreement, and are generally granted by private landlords. They are

normally arranged for a six-month period, but can be agreed for longer (e.g.

twelve months).

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 12

An assured shorthold tenancy is a type of assured tenancy. Therefore, the

conditions for creating assured shorthold tenancies are the same as for

assured tenancies (see (2) Assured tenancy above). However, from 28

th

February 1997, any new assured tenancy will automatically be an assured

shorthold tenancy unless it is expressly stated not to be one.

Assured shorthold tenancies are usually granted for an initial period of six

months. When this period has elapsed, unless a new tenancy is granted,

the assured shorthold tenant has no substantive security of tenure (and

becomes a statutory periodic assured shorthold tenant). This means

that the landlord does not require a ground or reason to evict the tenant, as

the landlord is entitled to possession as of right. However, the landlord is

required to serve a notice on the tenant seeking possession of the property,

and if the tenant refuses to leave the landlord will have to apply for a

possession order from the court.

(4) Introductory tenancy

Local authorities can adopt a scheme in which all new tenancies, which

would otherwise be secure tenancies, are granted on an introductory basis

for a probationary period of one year.

Section 125 Housing Act 1996 states that a tenancy will remain an

introductory tenancy until one year has passed unless:

Circumstances change and the tenancy would no longer qualify as a

secure tenancy (e.g. the tenant no longer lives in the dwelling house

as his/her only or principal home).

The local authority ceases to be the landlord.

The local authority revokes its introductory tenancy scheme.

The tenant dies and there is no one entitled to succeed.

The period of the introductory tenancy is extended by the local

authority.

The local authority starts a claim for possession.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 13

During the probationary period, the introductory tenant does not have

security of tenure, and this means that the local authority can more easily

evict the tenant (e.g. in the event of anti-social behaviour). At the end of

the probationary period the introductory tenancy automatically becomes a

secure tenancy (see (1) Secure tenancy above).

(5) Demoted tenancy

Certain social landlords, including local authorities, have the right to apply

to the court for an order demoting a secure tenancy or an assured tenancy.

Demotion is often sought as an alternative to possession in the event of

anti-social behaviour by the tenant (such as noise nuisance).

If a demotion order is made in relation to a secure tenancy, it brings the

secure tenancy to an end and replaces it with a demoted tenancy (non-

assured). After twelve months a demoted tenancy will revert to being a

secure tenancy unless, during the twelve month period, the landlord applies

for possession (s143B Housing Act 1996). However, if the tenant

commits a further act of anti-social behaviour, within the twelve month

period, the landlord can serve a notice seeking possession and apply to the

court for the tenancy to be terminated.

If a demotion order is made in respect of an assured tenancy, it brings the

assured tenancy to an end and replaces it with a demoted assured

shorthold tenancy. As with a demoted tenancy, the demoted assured

shorthold tenancy reverts to being an assured tenancy after twelve months

unless the landlord applies for a possession order.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 14

Glossary of key terms used in Part 1

Housing law involves a number of difficult legal concepts, and the key

terms are summarised below for ease of reference:

Term used

Meaning

assured shorthold

tenancy

This is a type of assured tenancy. Most commonly it relates to a

tenancy of a private dwelling house entered into with a private

landlord since 28/2/97.

assured tenancy

A tenancy of a dwelling house begun on or after 15/1/89 and which

is protected by Housing Act 1988. The tenant has greater security

of tenure than an assured shorthold tenant.

demoted assured

shorthold tenancy

The type of tenancy that comes into being when a demotion order

is made in relation to an assured tenancy. The tenancy will last for

12 months (unless a possession order is made in the meantime)

after which time the tenancy will revert to being fully assured.

demotion order

An order which a social landlord may obtain as an alternative to

possession, if the tenant has been guilty of antisocial behaviour. It

removes the tenant’s security of tenure for 12 months (unless a

possession order is made in the meantime).

demoted tenancy

(non-assured)

The type of tenancy that comes into being when a demotion order

is made in relation to a secure tenancy. The tenancy will last for 12

months (unless a possession order is made in the meantime) after

which time the tenancy will become secure.

fixed term tenancy

A fixed term tenancy states the length of time that the parties agree

the tenant may stay in the property (e.g. 6 months, or a year).

introductory tenancies

These are probationary tenancies that local authorities have been

able to offer new tenants since 12/2/97. They last for 12 months,

when they automatically convert into secure tenancies. However,

in the meantime, the tenant has very little security of tenure and

can be quickly evicted by court order obtained by the local

authority.

periodic tenancy

Unlike fixed term tenancies, periodic tenancies do not specify the

term for which the tenant is entitled to inhabit the dwelling. A

periodic tenant may continue to live in the property as long as s/he

pays rent, which, according to the tenancy, may be paid either

weekly, fortnightly, monthly, quarterly or annually.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 15

secure tenancy

A tenancy of a dwelling house let by a local authority to an

individual for use as his/her only or principal home. It may be

preceded by an introductory tenancy.

security of tenure

Legal protection given to certain categories of occupier of

residential property by which the landlord must obtain a court order

to recover possession of the accommodation.

tenancy

The legal contract between a tenant and a landlord. It may be

written or oral. The tenancy sets out the terms and conditions for

living in the property, as well as the obligations of the landlord and

tenant. This term tenancy is synonymous with the word “lease”,

though it is usually used to refer to short term occupation.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 16

Part 2 – Possession proceedings

There are a number of procedural requirements that must be complied with

before a landlord can evict a tenant. First, the landlord usually requires

grounds for possession. Second, the landlord must serve the tenant with

a possession notice confirming the landlord’s intention to seek a

possession order from the court. This Section will explain the various

grounds for possession available to landlords, and the information which

must be provided in a possession notice.

Even if the landlord complies with all of the necessary procedural

requirements, it is still possible for a tenant to defend possession

proceedings, and this Section will also discuss some of the key defences

available and where a tenant may be able to obtain advice about

possession proceedings.

Grounds for Possession

The grounds for possession differ depending on the type of tenancy. What

follows is a summary of each of the grounds. However, some of them are

not straightforward in their requirements, and advice from a solicitor may be

needed to establish whether all of the requirements have been complied

with.

Some of the grounds are mandatory, which means that the court must

order possession if the ground applies. Other grounds are discretionary,

which means that the court may grant a possession order, but only if the

court thinks that it is reasonable to grant an order. In some cases the court

can only issue a possession order if the landlord is able to provide suitable

alternative accommodation. The accommodation must be suitable for the

tenant’s specific needs, and so must be of the size and type that the tenant

requires, and the court must take into account the rent and security of

tenure. However, it does not have to be of the same standard as the

tenant’s present accommodation.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 17

If a tenant has a disability, and the disability relates to the application for

possession, then the possession proceeding may be considered

discriminatory under the Equality Act 2010 (see (4) Discrimination).

(1) Discretionary grounds and reasonableness

If a landlord is seeking possession under a discretionary ground, the

landlord will have to establish both that the ground is proved and that it is

reasonable for the court to grant an order, before a possession order is

made.

The court will consider all of the facts of the individual case when deciding

whether it is reasonable to make a possession order, including:

the financial positions of the parties;

the length of time the tenant has lived in the property;

the tenant’s previous conduct;

the health of the parties, including whether any of the parties has a

disability;

the age of the parties;

the interests of the wider public (which is particularly relevant in cases

involving anti-social behaviour).

Where the basis of the application is rent arrears, it is unusual for the court

to grant a possession order unless the arrears are substantial. Similarly, if

the tenant is in receipt of welfare benefits, and there has been a delay in

the benefits claim being processed, the court is likely to treat the tenant

sympathetically. However, where the tenant has a history of failing to pay

the rent, it is more likely that the court will conclude that it is reasonable to

make the possession order.

Where the basis of the application is breach of an obligation of the

tenancy, the court will look at the seriousness of the breach. If the breach

was trivial, and did not result in any significant loss to the landlord, then it is

unlikely that the court would find it reasonable to make a possession order.

Similarly, if the breach was committed innocently, and the tenant did not

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 18

realise that their actions amounted to a breach, the court is again unlikely

to find it reasonable to make a possession order. Even when a tenant

admits a breach, it is not inevitable that a possession order will be made as

the court may accept an undertaking from the tenant, which is a promise

to the court not to commit further breaches. Similarly, the court has power

to make a possession order but then suspend it on condition that the tenant

does not commit any further breach.

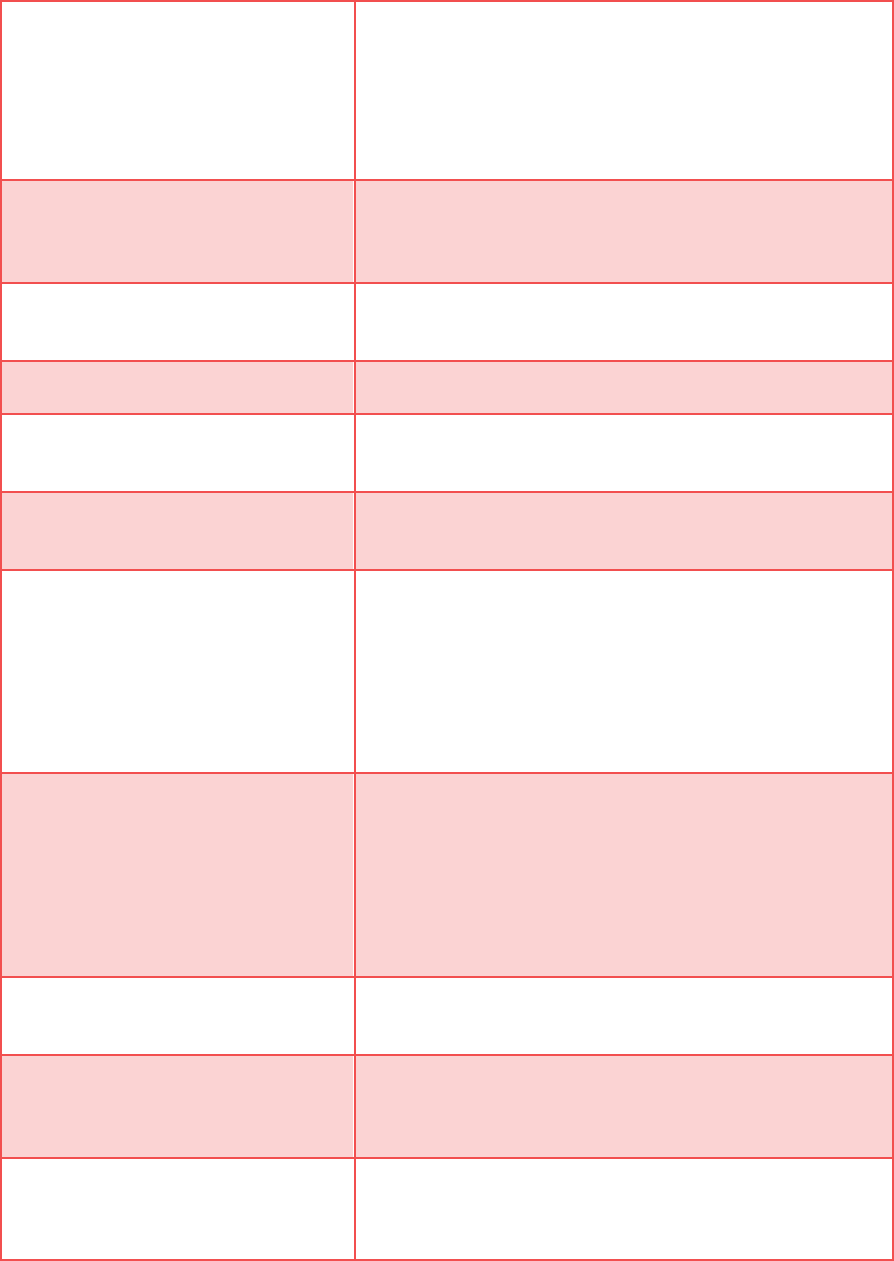

(2) Grounds for possession – secure tenancy

There are eighteen different grounds for possession where a tenant is a

secure tenant, and the grounds are summarised in Table 2. It should be

remembered that in most cases relating to secure tenancies, the landlord

will be a local authority.

Table 2: Grounds for possession – secure tenancy.

Ground

Description

(1) Rent arrears or other breach

of the tenancy agreement

Rent has not been paid by the tenant, or an

obligation of the tenancy has been broken or not

performed.

(2) Nuisance or annoyance or

criminal activity

The tenant (or a person living with the tenant) has

been causing a nuisance or annoyance to

neighbours, or other people living in or visiting the

area, or a serious criminal offence has been

committed by the tenant in the property or the local

area.

(2A) Domestic violence

Where the home is occupied by a married couple, or

civil partners, or co-habitees and one has left the

property because of violence, or threats of violence,

against them by the other and is not going to return.

(3) Deterioration in condition of

the property

The tenant has damaged or neglected the property or

common areas.

(4) Deterioration in the furniture

The tenant has damaged or neglected the furniture

in the property.

(5) Tenancy obtained by

deception

False information was given by the tenant prior to the

grant of the tenancy, in order to obtain the tenancy.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 19

(6) Payment of premium

Where the tenant exchanged their property with

another local authority tenant and money was paid

for the exchange.

(7) Non-housing accommodation

The accommodation must form part of a property,

which is used mainly for purposes other than

housing, and the accommodation must be let to the

tenant as part of their employment. The tenant (or a

person living with the tenant) must also act in a way

that conflicts with the purpose for which the property

is used, so that it is no longer suitable for the tenant

to continue to live in the accommodation. For

example, the tenant is a school caretaker and lives

in accommodation in the grounds of the school, and

then steals from the school.

(8) Temporary accommodation

The tenant moves into alternative premises as works

are being undertaken at their usual accommodation,

and on completion of the works the tenant refuses to

return to the original property.

(9) Overcrowding

The tenant is living in an overcrowded property

which breaks the law.

(10) Landlord’s works

The landlord intends to demolish, reconstruct or

carry out substantial work to the property in which

the tenant lives, or land around it, and cannot do this

whilst the tenant remains in the property.

(10A) Landlord seeking to sell the

property

The property is in an area, which forms part of a re-

development scheme, and the property is affected by

the scheme.

(11) Charitable landlords

The landlord is a charity and, if the tenant carried on

living at the property, this would be contrary to the

objects of the charity.

(12) Tied accommodation

As with Ground 7, the accommodation must form part

of a property, which is used mainly for purposes other

than housing, and the accommodation must be let to

the tenant as part of their employment. Here the

landlord is able to gain possession if the employment

has come to an end and the landlord needs the

accommodation for a new employee.

(13) Accommodation for the

disabled

The property is specially adapted for a physically

disabled person. The tenant does not have a

disability, and the landlord needs the property for

another disabled person.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 20

(14) Special needs

accommodation provided by

Housing Associations and Trusts

The property is reserved for a resident with special

needs and the current occupant does not have those

needs.

(15) Special needs

accommodation

The property is reserved for a resident with special

needs and social services support is provided within

close proximity. The current tenant does not have

those needs, and the landlord requires the property

for another person who does.

(16) Under occupation

The tenant has ‘succeeded’ to the tenancy on the

death of the original tenant, and the property is

considered too large for the current household.

Where a landlord is seeking a possession order in respect of a secure

tenancy, the approach the court will take will depend upon the grounds for

possession:

If Grounds 1 to 8 are relied upon, the court may order possession if it

is reasonable to do so.

If Grounds 9 to 11 are relied upon, the court may order possession if

suitable alternative accommodation is available.

If Grounds 12 to 16 are relied upon, the court may order possession if

it is reasonable to do so and suitable alternative accommodation is

available.

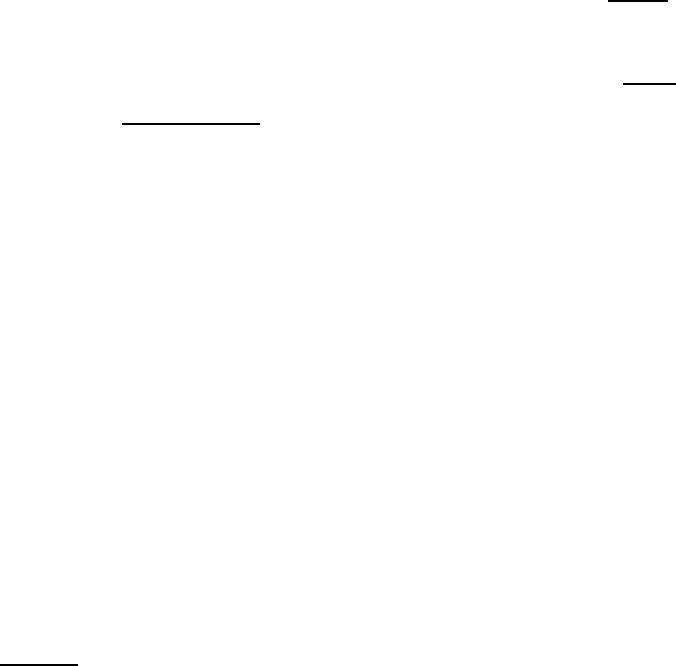

(3) Grounds for possession – assured tenancy

As with secure tenancies, there are eighteen different grounds for

possession where a tenant is an assured tenant. Whilst some grounds are

similar, they are not identical, and the grounds in respect of assured

tenancies are summarised in Table 3.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 21

Table 3: Grounds for possession – assured tenancy.

Ground

Description

(1) Owner-occupiers

The landlord previously lived in the property and now

requires it for own use. (The landlord must have

given notice to the tenant, before granting the

tenancy, that possession might be required on this

ground.)

(2) Mortgagees

Ground 1 must apply and the property must also be

subject to a mortgage (granted before the beginning

of the tenancy) and the lender is repossessing the

property.

(3) Tenancy preceded by ‘holiday

let’

The tenancy is a fixed term tenancy of less than 8

months, and was preceded by a letting for holiday

purposes. (The landlord must have given notice to

the tenant, before granting the tenancy, that

possession might be required on this ground.)

(4) Educational institutions

The tenancy is a fixed term tenancy of less than 12

months, and was previously let to a specified

educational institution. (The landlord must have given

notice to the tenant, before granting the tenancy, that

possession might be required on this ground.)

(5) Minister of religion

The property is held for religious purposes and a

minister of religion requires it. (The landlord must

have given notice to the tenant, before granting the

tenancy, that possession might be required on this

ground.)

(6) Demolition or reconstruction

The landlord intends to demolish, or carry out

substantial work to the property, and the intended

work cannot reasonably be carried out without the

tenant giving up possession.

(7) Death of the tenant

The tenancy is a periodic tenancy (including a

statutory periodic tenancy) which has passed under

a Will or intestacy to a relative of the former tenant.

The landlord may obtain possession if proceedings

are brought within 12 months of the death of the

tenant, or the date when the landlord became aware

of the death.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 22

(8) Eight weeks’ or two months’

rent arrears

The tenant is at least 8 weeks in arrears (if paying

weekly/fortnightly), or at least 2 months in arrears (if

paying monthly), or 3 months in arrears (if paying

quarterly or annually). (The arrears must be due

both at the date the landlord serves notice and at the

date of the court hearing.)

(9) Suitable alternative

accommodation

Suitable alternative accommodation is available for

the tenant, or will be available when the order for

possession takes effect.

(10) Rent arrears

Some rent is due from the tenant (at the date of the

notice or court proceedings).

(11) Persistent delay in paying

rent.

The tenant persistently delays paying rent.

(12) Breach of any obligation

A condition of the tenancy, other than one relating to

the payment of rent, has been broken.

(13) Waste or neglect

The tenant has damaged or neglected the property

or any of its common areas.

(14) Nuisance or annoyance or

criminal conviction

The tenant (or a person living with the tenant) has

been causing a nuisance or annoyance to

neighbours, or other people living in or visiting the

area, or a serious criminal offence has been

committed by the tenant in the property or the local

area.

(14A) Violence to occupier

Where the home is occupied by a married couple, or

civil partners, or co-habitees and one has left the

property because of violence or threats of violence

against them by the other and is not going to return.

(This ground can only be used by registered

providers of social housing or charitable trusts, and

cannot be used by private landlords.)

(15) Deterioration of furniture

The condition of any furniture provided for use under

the tenancy has, in the opinion of the court,

deteriorated owing to neglect by the tenant.

(16) Premises let to employees

The property was let to the tenant in consequence of

employment, and the tenant has now left that

employment

.

(17) Tenancy induced by false

statement

False information was given by the tenant to acquire

the tenancy.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 23

Where a landlord is seeking a possession order in respect of an assured

tenancy, the approach the court will take will depend upon the grounds for

possession:

If Grounds 1 to 8 are relied upon, the court must order possession if it

is satisfied that the ground is established.

If Grounds 9 to 17 are relied upon, the court may order possession if

it is reasonable to do so.

(4) Grounds for possession – assured shorthold tenancy

Assured shorthold tenancies are usually granted for a period of six months.

When this period has elapsed, unless a new tenancy is granted, the

assured shorthold tenant has no substantive security of tenure (and

becomes a statutory periodic assured shorthold tenant). This means that

the landlord does not require a ground or reason to evict the tenant as the

landlord is entitled to possession as of right. However, the landlord is

required to serve a notice on the tenant seeking possession of the property,

and if the tenant refuses to leave the landlord will have to apply for a

possession order from the court.

If the landlord wishes to bring an assured shorthold tenancy to an end

during the initial period of the tenancy, an application must be made to the

court for a possession order, and the landlord will have to establish one of

the grounds for possession for assured tenancies (see (3) Grounds for

possession – assured tenancy).

(5) Grounds for possession – introductory and demoted tenancies

There are no statutory grounds for possession in respect of these types of

tenancy. However, before a landlord can evict an introductory or demoted

tenant, notice has to be given to the tenant and a possession order

obtained from the court. The landlord must have a valid reason for seeking

possession, and the most common reasons are rent arrears or anti-social

behaviour by the tenant.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 24

Possession Notices

Before court proceedings can be commenced to evict a tenant, a landlord

is usually required to send the tenant a possession notice stating his

intention to seek an order for possession. The type of notice required

depends on the type of tenancy.

(1) Notice requirements for secure and assured tenancies

The requirements are set out in s83 Housing Act 1985 (secure tenancy)

and s8 Housing Act 1988 (assured tenancy). The notice must:

specify one or more of the statutory grounds;

give an explanation of why each ground is being relied on; and

state the earliest date on which the claim can be commenced.

If the notice is completed incorrectly, and the prescribed information is

omitted, the notice will be invalid. However, where there are only minor

errors or inaccuracies in the notice, or the notice is “substantially to the

same effect” as a properly drafted notice, the court will still usually accept it.

Examples of the prescribed notices seeking possession for secure and

assured tenancies are set out in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

The notice period in the case of a secure tenancy is at least 28 days,

except where the nuisance ground is relied upon. If the nuisance ground is

relied upon, the landlord is entitled to commence proceedings immediately.

The notice period in the case of an assured tenancy is either two weeks or

two months. However, where the nuisance ground is relied on then the

landlord is again entitled to commence proceedings immediately.

(2) Notice requirements for assured shorthold tenancies

The requirements are set out in s8 and s21 Housing Act 1988. Assured

shorthold tenancies are always made for a fixed-term (usually 6 months),

and the landlord is entitled to an order for possession as of right once the

fixed-term has expired. No ground for possession is required. However,

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 25

the landlord is still required to give the tenant notice requiring possession,

and the notice requirements vary depending upon when notice is given.

If notice is given before the end of the fixed-term period, then s21 simply

requires the landlord to give not less than two months’ notice in writing.

Therefore, at any point up until the last day of the fixed term, the landlord

simply has to give at least two months’ written notice. Sometimes, the

landlord will provide notice at the start of the tenancy, and this is legitimate

as the landlord is simply indicating that once the fixed-term expires

possession of the property will be required.

If notice is not given during the fixed-term period, then the tenant becomes

a statutory periodic assured shorthold tenant. What this means is that,

when the fixed-term tenancy expires, the law deems the tenant to have

been granted a periodic tenancy on the expiry of their fixed-term tenancy.

The periodic tenancy does not have an end date and runs from week to

week, or month to month, depending on how the rent is calculated. If the

tenant becomes a statutory periodic assured shorthold tenant, s21 requires

the landlord to provide a more detailed notice which must:

be in writing;

state that possession is required under s21;

state that possession is required after a specific date, which must be

the last day of the period of the tenancy and at least two months after

the notice was given.

These provisions are complex and if there is any doubt that s21 has been

complied with the tenant should seek legal advice as a defective s21 notice

may invalidate any subsequent possession order. For example, in

McDonald & Anor v J Fernandez & Anor [2003] EWCA Civ 1219, the

Court of Appeal set aside a possession order as the notice period was

phrased incorrectly. The tenancy had become a monthly statutory periodic

assured shorthold tenancy, running from 4

th

of the month to the 3

rd

of the

month. The possession notice stated that possession was required “on 4

th

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 26

January 2003”. The Court of Appeal ruled that this wording was incorrect

as s21 requires the notice to state that possession is required after a

specific date, which must be the last day of the period of the tenancy.

Therefore, as the tenancy ran to the 3

rd

of each month, the required

wording was “after 3

rd

January 2003”.

If the landlord wishes to bring an assured shorthold tenancy to an end

during the fixed-term period of the tenancy, s8 requires that an application

is made to the court for a possession order, and the landlord will have to

establish one of the grounds for possession for assured tenancies.

(3) Notice requirements for introductory and demoted tenancies

The requirements are set out in s123 Housing Act 1996 (introductory

tenancy) and s143 Housing Act 1996 (demoted tenancy). Again, there is

no prescribed form for the notice for an introductory or a demoted tenancy,

but the document provided by the landlord must state:

the reasons for the landlord’s decision to apply for a possession

order;

the date that the court will be asked to make an order for possession;

the earliest date that proceedings can be commenced;

that the tenant has the right to ask the landlord to review the decision

to seek a possession order within 14 days; and

that if the tenant needs assistance to deal with the notice, this should

be sought immediately from a Citizens Advice Bureau, Housing Aid

Centre or solicitor.

The notice period in the case of both introductory and demoted

tenancies is at least 28 days. If the tenant requests a review, it must be

conducted by a representative of the landlord who was not involved in the

decision to apply for the possession order. The tenant is entitled to request

that the review is conducted by way of a hearing, and the tenant is entitled

to attend the hearing with a representative. (The review process is

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 27

governed by either the Introductory Tenants (Review) Regulations 1997

or the Demoted Tenancies (Review of Decisions) Regulations 2004.)

(4) Rent arrears and social housing

If a tenant is renting a property from either a local authority or other social

landlord, there are court rules which the landlord must comply with before

commencing possession proceedings for rent arrears. The procedure is

set out in Part 2 of the Pre-Action Protocol for Possession Claims by Social

Landlords (the Protocol). The key requirements of the Protocol are

summarised below.

When a tenant first falls behind with their rent, the landlord should contact

the tenant as soon as possible to discuss their financial circumstances and

how they plan to pay the arrears. Where there are joint tenants, the

landlord should contact each separately to ensure that everyone is aware

of the problem. The landlord should send the tenant quarterly rent

statements showing how much rent is due and what payments have been

received.

The landlord should also discuss any entitlement to welfare benefits. It is

important to ensure that a tenant is receiving all the benefits to which they

are entitled, particularly housing benefit. If a tenant is receiving welfare

benefits, but finds budgeting difficult, then it may be possible to arrange for

the tenant’s rent to be deducted from their benefits and paid directly to the

landlord. A landlord should not start possession proceedings if:

the tenant has applied for housing benefit; and

it is likely that the tenant will be eligible for housing benefit; and

the tenant can make up any sums not covered by their housing

benefit.

If the landlord decides to seek a possession order, they must first send the

tenant a notice stating the intention to seek an order for possession. The

notice must comply with the required formalities (as discussed above).

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 28

After giving notice, the landlord should make reasonable attempts to

contact the tenant to discuss their arrears. The landlord must do

this before beginning court proceedings. If the tenant can pay a

reasonable amount to reduce the arrears and continue to pay the rents in

future, the landlord should agree to postpone any court action.

If a tenant is vulnerable the landlord should also consider whether:

the tenant has been discriminated against because of their

vulnerability;

the tenant may be entitled to a social care assessment;

the tenant would have capacity to represent themselves at court if

possession proceedings are commenced.

A vulnerable tenant would include someone who is disabled, elderly or

suffering from a mental illness, or someone under 18 years old.

Key Information and Resources:

Protecting vulnerable tenants

In addition to the requirements under the Protocol, individual local

authorities (and other social housing providers) may also have their own

policies dealing with the treatment of vulnerable people. Most local

authorities post their procedures on their websites, and if you are

supporting a tenant who is vulnerable it is important to check whether the

landlord has its own policy and, if so, whether the landlord has complied

with the terms of the policy.

If the landlord decides to apply for a possession order, then, at least ten

days before the court hearing, the landlord must:

supply the tenant with an up-to-date rent statement, detailing the

arrears;

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 29

provide the tenant with the date of the court hearing and advise them

that if they do not attend their home may be at risk; and

provide the court with information about the tenant’s housing benefit

position.

If the landlord fails to comply with the requirements of the Protocol, the

court will require an explanation regarding why the Protocol has not been

complied with and can:

Adjourn, strike out or dismiss the landlord's application. (This can

only happen if the landlord is seeking to evict a tenant under a

'discretionary' rather than a ‘mandatory’ ground.)

Decide that the landlord must pay the court costs. (This can happen

even if the landlord succeeds in obtaining an order for possession.)

Defences to Possession Claims

Even if the landlord has complied with all of the necessary procedural

requirements, it is still possible for a tenant to defend possession

proceedings, and some of the key defences available are discussed below.

If a tenant is going to try and defend possession proceedings, it is essential

that the tenant gathers together all the evidence they have to support their

position. For example, if the tenant has a disability then evidence of the

nature of the disability and how it affects the tenant (e.g. assessments or

care plans) will be very important. Similarly, if the tenant’s position is that

the landlord gave permission for the tenant to act in a particular way, then

evidence of the permission (e.g. letters, emails or logs of telephone calls)

will be vital.

(1) Defective possession notice

As discussed previously, a notice seeking possession must usually be sent

to the tenant before court proceedings are commenced (see Possession

Notices). If the notice is defective, for example it is not in the prescribed

form or the grounds or reasons for possession are inaccurate or unclear,

then the court may refuse to grant an order.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 30

Every notice sent by a landlord should, therefore, be examined carefully to

see whether it is valid. For example, in Manel v Memon [2001] 33 HLR 24

CA a notice was held to be defective because it omitted the required

statement explaining the tenant’s right to seek legal advice.

(2) Landlord’s failure to establish grounds for possession

It is the landlord’s responsibility to satisfy the court that the ground(s) for

possession are established. If the landlord cannot prove the ground, the

court will not make a possession order.

(3) Reasonableness

As discussed previously, where a landlord is relying on a ‘discretionary

ground’ it is the landlord’s responsibility to establish both that the ground for

possession is made out on the facts and that it is reasonable to grant a

possession order (see Grounds for possession - (1) Discretionary grounds and

reasonableness).

(4) Discrimination

The Equality Act 2010 (EA 2010) came into force on 1 October 2010. Its

purpose was to reform and harmonise equality law, and it amalgamated

over a hundred pieces of legislation, including the Disability Discrimination

Act 1995. The EA 2010 outlaws discrimination, which arises due to the

person being discriminated against having a ‘protected characteristic’.

Under s4 EA 2010, disability is classed as a protected characteristic. This

means that it is unlawful to treat someone unfairly due to their disability. A

person has a disability if:

they have a physical or mental impairment; and

the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on

their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

Schedule 1 EA 2010 further explains disability. Paragraph 2 notes that

‘long-term adverse effect’ means that it has lasted, or is likely to last, at

least 12 months or for the rest of the person’s life. Paragraph 6 notes

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 31

where a person has cancer, HIV infection or multiple sclerosis, the person

is automatically treated as disabled and it is not necessary to establish an

effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

Paragraph 8 takes into account progressive conditions, so a disability that

is not presently having a substantial adverse effect on a person’s ability to

carry out normal day-to-day activities, but which is likely to recur, is

covered.

Learning disabilities may be treated as a disability under the EA 2010

provided a long term and substantial effect on a person’s daily life can be

established. Relevant issues may include:

behavioural difficulties;

speech difficulties;

difficulty using a computer;

difficulty reading and writing;

the need for special equipment.

The EA 2010 defines discrimination in two ways: direct discrimination

and indirect discrimination.

Under s13 EA 2010 direct discrimination occurs if person A treats person B

differently or less favourably because of a protected characteristic.

However, it is not discrimination to treat a disabled person more favourably

than a non-disabled person.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 32

Key Information and Resources:

Example – direct discrimination

A landlord gives notice to evict the tenant, and says that this is because

members of the Resident’s Association have put pressure on him to give

the notice because of the tenant’s severe learning disability.

This is direct discrimination. The tenant is being treated differently or

less favourably because of his disability, which is a protected

characteristic. The landlord would not have given notice if the tenant had

not been disabled.

Under s19 EA 2010 indirect discrimination occurs if person A applies a

provision, criterion or practice to person B which is discriminatory in relation

to a relevant protected characteristic. Generally, a ‘provision, criterion or

practice’ will be discriminatory if it puts people who share B’s protected

characteristic at a particular disadvantage when compared with people who

do not share the particular characteristic.

Key Information and Resources:

Example – indirect discrimination

A tenant uses a wheelchair and also has a severe learning disability.

The Local Authority allocates housing using a choice based letting

system, which means that the tenant needs to bid for housing online.

The tenant finds this difficult due to her learning disability, and needs help

with the bidding process. It is also difficult for the tenant to travel to the

Local Authority offices to bid for properties.

Although the choice based system applies to everyone who needs social

housing, it could amount to indirect discrimination as it places the

tenant, and other disabled people like her, at a disadvantage.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 33

Where person A applies a provision, criterion or practice which is

discriminatory, person A’s actions will not amount to indirect discrimination

if they are a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. Examples

of legitimate aims are:

health and safety, and welfare of individuals;

running an efficient service;

requirements of a business; and

desire to make profit.

As well as being legitimate, the aim must also be proportionate. This

means that the reason behind the discrimination must be fairly balanced

against the disadvantage a tenant has suffered because of the

discrimination. Effectively, person A will have to establish that their actions

are objectively justified. If there are better and less discriminatory ways of

doing things, it will be more difficult to justify discrimination, and economic

reasons alone are never enough to justify discrimination.

The general protection available in respect of direct and indirect

discrimination applies to all protected characteristics. Where the relevant

protected characteristic is disability, s15 EA 2010 provides additional

protection against disability discrimination. Disability discrimination will

occur where person A treats person B unfavourably because of person B’s

disability, and person A cannot show that the treatment is a proportionate

means of achieving a legitimate aim.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 34

Key Information and Resources:

Example – disability discrimination

A homeless person applies to a Local Authority for emergency housing.

The person in question has Tourette’s syndrome, which causes him to

swear a lot. A note of this is placed on his file. However, when the time

comes for his interview, the Local Authority officer refuses to interview

him because of his swearing.

The refusal to conduct an interview could amount to disability

discrimination as it is connected to the person’s disability.

However, s15 EA 2010 also states that the treatment of person B will not

amount to disability discrimination if person A can show that they did not

know, and could not reasonably have been expected to know, that person

B had a disability. Even if it can be established that person A knew, or

ought to have known, of the disability person A may still be able to avoid a

claim of disability discrimination if person A can establish that the treatment

of person B was a ‘proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim’ (i.e.

that is was objectively justified).

The provisions relating to direct, indirect and disability discrimination may

all be relevant in the context of a claim for possession, and a tenant may

rely on one or more of the provisions to defend the claim. In addition, s35

EA 2010 provides that:

A person (A), who manages premises, must not discriminate against

a person (B) who occupies the premises:

a. in the way in which A allows B to make use of a benefit or

facility;

b. by evicting B, or taking steps to secure B’s eviction;

c. by subjecting B to any other detriment.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 35

Where the landlord is a public authority, the tenant may also be able to rely

on the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) under s149 EA 2010, which

provides that:

A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due

regard to the need to:

a. eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any

other conduct that is prohibited by EA 2010;

b. advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a

relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share

it;

c. foster good relations between persons who share a relevant

protected characteristic and persons who do not share it.

Public authorities are defined in Schedule 19 EA 2010, and include Local

Authorities. Housing associations are not included within this definition, but

s149 requires organisations, which are not public authorities but which

exercise public functions, to have due regard to the requirements of s149.

The following cases provide examples where the courts have upheld

defences based on discrimination in housing disputes:

North Devon Homes v Brazier [2003] EWHC 574 (QB) – The tenant was

exhibiting anti-social behaviour, which was related to mental illness, and

the landlord commenced possession proceedings. The landlord argued

that it would not have treated a non-disabled person, who had behaved in

the same way, any differently. The court held that a possession order was

not justified, noting: there was no evidence that the landlord had even

considered whether the eviction was justified, a psychiatric report made it

clear the eviction would lead to a serious deterioration in the tenant’s health

and, although the neighbours suffered considerable inconvenience as a

result of the tenant’s behaviour, their health and safety were not

endangered. Although the fact that an eviction would be unlawful under the

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 36

Disability Discrimination 1995 Act did not determine whether it was

reasonable to grant a possession order, it was highly relevant to the court’s

exercise of its discretion. (Although this was a case decided under the

Disability Discrimination Act 1995, it is likely that the principles considered

would apply under the EA 2010 as s149 EA 2010 imposes the same duty

as s49A Disability Discrimination Act 1995.)

Pieretti v London Borough of Enfield [2010] EWCA Civ 1104 - In this

case the local authority was challenged for failing to comply with the Public

Sector Equality Duty (PSED) when considering an application for

accommodation from a disabled couple who had been evicted from their

rented property. The local authority argued that they had made themselves

intentionally homeless. The Court of Appeal held that the reviewing officer

breached the PSED by failing to take appropriate steps to take account of

the tenant’s disability. This was because no enquiries had been made to

establish the extent to which they could be said to have become

intentionally homeless.

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council v Norton & Ors [2011] EWCA

Civ 834 - Following termination of the first defendant’s employment for

misconduct, the local authority brought possession proceedings in order to

accommodate a new caretaker. The tenant lived in the property with his

wife and daughter, and his daughter had cerebral palsy and epilepsy. It

was accepted that the daughter had a disability for the purposes of the EA

2010. As the daughter’s health could be critically affected by the local

authority obtaining a possession order, it was under a duty to have regard

to her disability at the time when the decision was taken to commence

possession proceedings and failure to do so was a breach of that legal

duty. Although the Court of Appeal did not set the possession order aside,

it noted that the local authority had a duty to re-house the family and that it

expected the new accommodation to be available before the possession

order was enforced.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 37

Akerman- Livingstone v Aster Communities Ltd [2015] UKSC 15 - the

Supreme Court confirmed that the EA 2010 applies to both private and

public landlords. The Court also noted that there are two key questions to

be considered in disability discrimination cases:

i. whether the eviction was due to something arising as a result of the

tenant’s disability;

ii. whether the landlord can show that the eviction is a proportionate

means of achieving a legitimate aim.

If the tenant can establish that the eviction was related to their disability,

the landlord must then prove that the eviction was a proportionate means of

achieving a legitimate aim. The Court noted that enabling the landlord to

exercise their property rights will not necessarily make an eviction

proportionate, and the landlord will have to establish that there were no

less drastic measures available and that the effect on the tenant was

outweighed by the advantages.

(5) Public law defences

A public law defence is only available where the landlord is a public body

(such as a local authority), and so is not available where the landlord is a

private individual. Public bodies must act fairly, and must consider the

individual circumstances of each case. Sometimes this is referred to as

acting in accordance with ‘the rules of natural justice’. For example, if a

noise complaint is made against a tenant of a local authority, the rules of

natural justice require the tenant to be given an opportunity to respond to

the allegation.

Public bodies make a series of decisions during the course of possession

proceedings, including:

to serve notice seeking possession;

to review or not to review this decision;

to issue proceedings at court;

to pursue the proceedings after seeing the tenant’s defence;

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 38

to execute the possession order once it is granted by the court.

At each of these stages the local authority is under a duty to ensure that it

is acting reasonably, and if it fails to act reasonably at any stage the court

may grant the tenant relief (e.g. by refusing to make, or setting aside, the

possession order) (see Salford City Council v Mullen & Ors [2010]

EWCA Civ 336).

Where a local authority fails to follow its own policies and procedures, it is

very likely that the court would find that the local authority had acted

unlawfully. Therefore, if you are supporting a tenant and the landlord is a

public body, it is essential that you check whether the landlord has a

relevant policy and whether it has been complied with (e.g. policies relating

to equality, rent arrears, housing strategy, vulnerable tenants and

homelessness).

Some examples of cases where the court has allowed the tenant to rely on

a public law defence are:

McGlynn v Welwyn Hatfield District Council [2009] EWCA Civ 285 -

Complaints of anti-social behaviour were made against a tenant, and the

local authority served a possession notice indicating that the local authority

would seek a possession order if the anti-social behaviour continued. The

court held that the local authority had failed to follow the rules of natural

justice, as the tenant had not been given a sufficient opportunity to respond

to the allegations.

Barber v London Borough of Croydon [2010] EWCA Civ - The tenant

was violent and abusive towards a resident caretaker, and the local

authority served a possession notice and issued possession proceedings.

During proceedings it came to light the tenant had severe mental health

problems, and that his behaviour was a result of this. The court held that in

deciding to carry on with the proceedings the local authority had failed to

have regard to its own policies and procedures relating to the management

of anti-social behaviour by vulnerable tenants.

HOUSING LAW: SUPPORTING TENANTS WITH A DISABILITY – AUGUST 2015 39

Eastlands Homes Partnership Ltd v Whyte [2010] EWHC 695 (QB) -

The landlord served a possession notice due to rent arrears and anti-social

behaviour. The court held that the landlord had failed to follow its own

policy in relation to rent arrears. (It should be noted that the law does not

require landlords to have policies and procedures in place, but if a policy

exists then it must be followed.)

(6) Human Rights Act defences

The Human Rights Act 1998 came into force on the 2

nd

October 2000. It

incorporated into UK law most of the rights contained in the European

Convention on Human Rights. As with public law defences, a defence