LESTER

CROWN CENTER

ON US FOREIGN POLICY

By Dina Smeltz,

Ivo Daalder,

Karl Friedho,

Craig Kafura, and

Emily Sullivan

A Foreign Policy

for the Middle

Class—What

Americans Think

RESULTS OF THE 2021 CHICAGO

COUNCIL SURVEY OF AMERICAN PUBLIC

OPINION AND US FOREIGN POLICY

2021 Chicago Council

Survey Team

Meghan Bradley

Intern, Chicago Council on

Global Aairs

Karl Friedho

Marshall M. Bouton Fellow, Public

Opinion and Asia Policy, Chicago

Council on Global Aairs

Craig Kafura

Assistant Director, Public Opinion

and Foreign Policy, Chicago

Council on Global Aairs

Fosca Majnoni d’Intignano

Intern, Chicago Council on

Global Aairs

Dina Smeltz

Senior Fellow, Public Opinion and

Foreign Policy, Chicago Council

on Global Aairs

Katherine Stiplosek

Intern, Chicago Council on

Global Aairs

Emily Sullivan

Research Assistant, Chicago

Council on Global Aairs

Colin Wol

Intern, Chicago Council on

Global Aairs

Foreign Policy Advisory Board

Joshua Busby

Associate Professor of Public

Aairs, Lyndon B. Johnson School

of Public Aairs, University of

Texas at Austin

Ivo Daalder

President, Chicago Council on

Global Aairs

Michael Desch

Packey J. Dee Professor

of International Relations,

Department of Political Science,

University of Notre Dame

Daniel Drezner

Professor of International Politics,

Fletcher School of Law and

Diplomacy, Tufts University

Peter Feaver

Professor of Political Science and

Public Policy, Duke University

Richard Fontaine

CEO, Center for a New American

Security

Brian Hanson

Vice President of Studies,

Chicago Council on Global Aairs

Bruce Jentleson

William Preston Few Professor

of Public Policy and Political

Science, Sanford School of Public

Policy, Duke University

Ellen Laipson

Distinguished Fellow and

President Emeritus, Stimson

Center

Tod Lindberg

Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

James Lindsay

Senior Vice President, Director

of Studies, Chair, Council on

Foreign Relations

Diana Mutz

Samuel A. Stouer Professor

of Political Science and

Communication, Director

of the Institute for the Study of

Citizens and Politics, University

of Pennsylvania

Robert Pape

Professor of Political Science,

University of Chicago

Kori Schake

Senior Fellow and Director of

Foreign and Defense Policy

Studies, American Enterprise

Institute

James Steinberg

Incoming Dean, John Hopkins

School of Advanced International

Studies

The Chicago Council on Global

Aairs is an independent,

nonpartisan organization.

All statements of fact and

expressions of opinion contained

in this report are the sole

responsibility of the authors and

do not necessarily reflect the

views of the Chicago Council on

Global Aairs or of the project

funders.

Copyright © 2021 by the Chicago

Council on Global Aairs. All

rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of

America.

This report may not be

reproduced in whole or in

part, in any form (beyond that

copying permitted by sections

107 and 108 of the US Copyright

Law and excerpts by reviewers

for the public press), without

written permission from the

publisher. For further information

about the Chicago Council or

this study, please write to the

Chicago Council on Global Aairs,

Prudential Plaza, 180 North

Stetson Avenue, Suite 1400,

Chicago, Illinois 60601, or visit

thechicagocouncil.org.

Photography:

GeorgePeters/iStock

carterdayne/iStock

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

2

CONCLUSION METHODOLOGY APPENDIX

34

36

38

DEFINING THE

MIDDLE CLASS

INTRODUCTION

1311

LINKAGES BETWEEN

US DOMESTIC AND

FOREIGN POLICIES

13

US MILITARY

SUPERIORITY

AND PRESENCE

ABROAD

29

BUILDING AT HOME

TO COMPETE WITH

CHINA ABROAD

18

EFFORTS TO

RESTORE US

LEADERSHIP

26

REVITALIZING

ALLIES AND

PARTNERS

31

ENDNOTES

42

2

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In his inaugural speech, US President Joe Biden ticked o a range of challenges confronting the country.

“We face an attack on democracy and on truth. A raging virus. Growing inequity. The sting of systemic

racism. A climate in crisis. America’s role in the world. Any one of these would be enough to challenge

us in profound ways. But the fact is we face them all at once, presenting this nation with the gravest of

responsibilities.”

1

To meet this responsibility, President Biden and his administration propose a “Foreign Policy for the

Middle Class,” which aims to simultaneously meet America's challenges at home and abroad.

2

At its core, the Foreign Policy for the Middle Class is about recognizing the linkages between American

domestic strength and US ability to maintain international competitiveness. It emphasizes investing

at home—in recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, infrastructure, green technology, and a range

of other social and domestic programs. With these investments, the administration aims to equip

American workers, companies, and the government to compete with—and outperform—international

competitors. That means investing in American businesses that operate in strategic sectors, research and

development, and American jobs and wages rather than focusing on expansive trade deals.

By “building back better” at home, the administration seeks to revitalize the US strength and dynamism

needed for the growing political, economic, and security competition with China. To prevail in that

competition, the Biden team is intent on restoring US alliances and working with allies to confront

adversaries and to address the most pressing global problems. US ocials also consider this competition

a challenge between democracies and autocracies, and which system can better deliver concrete results

for everyday citizens. They call for not only restoring democracy at home but also elevating the centrality

of human rights. And most of all, the Biden team argues that American leadership and engagement

matter. “We must demonstrate clearly to the American people that leading the world isn’t an investment

we make to feel good about ourselves,” Biden has argued.

3

“It’s how we ensure the American people are

able to live in peace, security, and prosperity. It’s in our undeniable self-interest.”

The idea of a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class has not been without its critics. There is confusion and

debate about how this policy would be formulated—with some arguing it is little more than a slogan.

Some point to the populist tinge inherent in these ideas,

4

with similarities to the last administration's

America First policies. Others think of it as “Trumpism with a human face,”

5

focusing on the well-being of

Americans first but without the divisive nationalism that alienated some Americans and denigrated US

allies.

6

Another commentator points out that the economic well-being of the middle class is determined

less by foreign policy and more by domestic policy—“where the politics are fiercer, congressional

influence is stronger, and presidents enjoy less freedom of action.”

7

Other skeptics fault the Biden

strategy for incorporating “bad economics and class warfare” into US foreign policy.

8

And even those

columnists who acknowledge some of the merits of the policy assert that “proposing a middle class

litmus test for every major decision” risks setting impossible standards.

9

3

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

The controversial decision to remove US troops from Afghanistan has been the most high-profile example

of the Biden strategy, demonstrating the administration’s commitment to refocusing American eorts

and resources on initiatives with more tangible payos for the American people. Critics say that the way

the withdrawal was executed has hurt US credibility with our allies and has risked deflating confidence in

traditional political leadership,

10

perhaps giving energy to authoritarian politicians such as Trump.

11

A solid

majority of Americans have consistently supported the withdrawal. But beyond Afghanistan, a Foreign

Policy for the Middle Class could have potential ramifications across all facets of US foreign policy,

including US trade policy, US alliances, US leadership on global issues, and relations with China.

The 2021 Chicago Council Survey finds that Americans welcome several of the major ideas underpinning

a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class. The public sees large businesses (59%) and the wealthy (50%) as

benefiting a great deal from US foreign policy, rather than the American middle class (11%). Americans see

China as a rising economic and military power, one that seeks to replace the United States as the leading

power in the world. And Americans think that by making concrete progress at home—by improving

education, strengthening democracy, and maintaining US economic power—the United States can

enhance its global influence.

While many of the administration’s foreign policy priorities are also priorities for the US public, that is

not universally true. The public is less interested in promoting human rights and democracy abroad

than the administration proclaims to be. And the data also seem to disprove some of the assumptions

undergirding the administration’s approach to foreign policy—namely, that Americans are skeptical about

trade and wary of US global engagement and leadership.

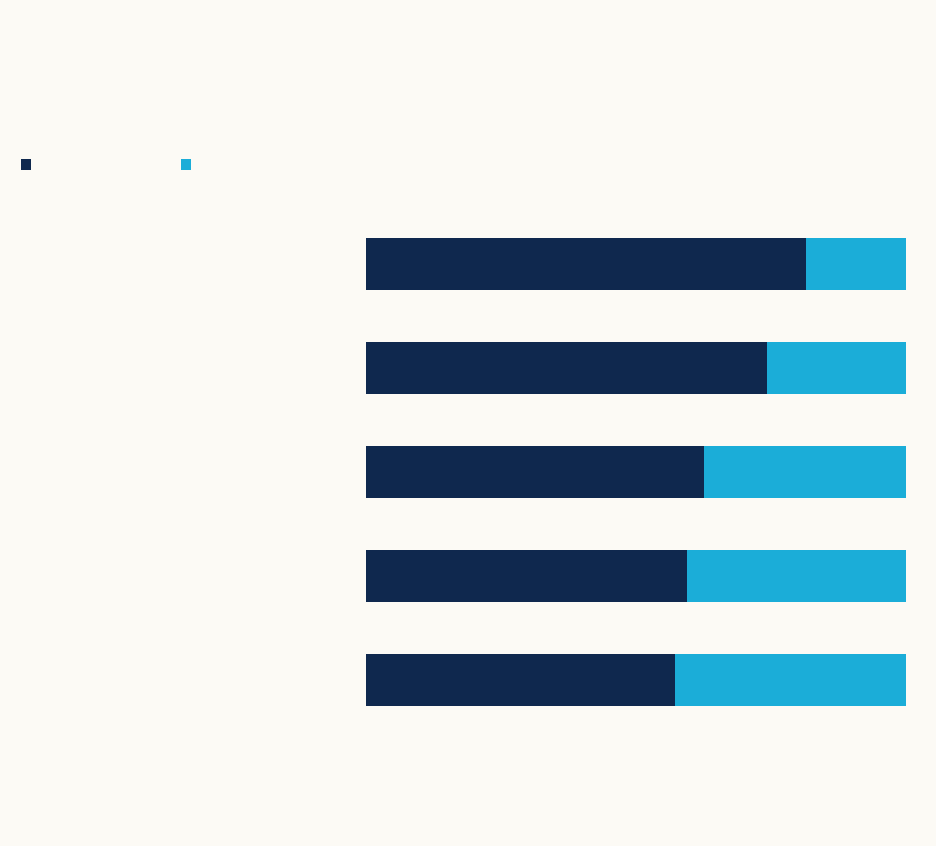

Americans Support Focusing on Domestic Improvement

A key feature of the Foreign Policy for the Middle Class is the link between domestic investments and

international influence. In fact, the factors seen by most Americans as very important for maintaining

US international influence are domestically focused. Majorities of Americans consider improving public

education (73%), strengthening democracy at home (70%), and reducing both racial (53%) and economic

inequality (50%) as very important to maintaining America’s global influence (Figure A). But those are not

the only factors important to the public; Americans also see maintaining US economic power (66%) and

American military superiority (57%) as key elements to US global influence. It is these latter elements that

Americans also see as being directly challenged by a rising China.

While Americans have been supportive of public spending on infrastructure for decades, according

to Chicago Council Surveys, they do not appear to make a connection between infrastructure

improvements at home and benefits to US influence overseas. The public rates the importance of

improving infrastructure relatively low (10th out of 12 items that are very important to retaining US global

influence). Promoting democracy and human rights around the world, taking leadership on international

issues, and participating in international organizations are similarly low on this list.

4

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Americans Sense China Is Catching Up to the United States

A major aim of the administration’s policies, Biden has argued, is to prepare the United States to face the

challenges to US prosperity, security, and democratic values presented by “our most serious competitor,

China.”

12

Americans are broadly concerned about competition from China, and they are notably less

confident in US economic and military strength compared with China now than they were two years

ago. A plurality of Americans (40%) say China is economically stronger than the United States, up from

31 percent who said the same in 2019 (Figure B); only a quarter (27%) see the United States as stronger

(down from 38% in 2019). And for the first time in Council polling, fewer than half of Americans (46%) say

the United States is stronger than China in terms of military power, down from 58 percent who said the

same in 2019 (Figure C).

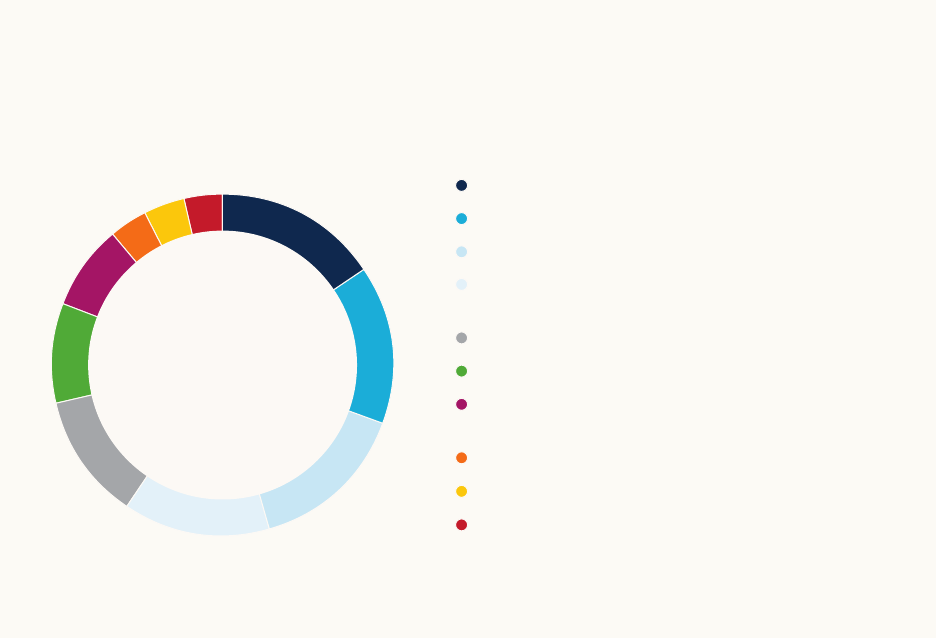

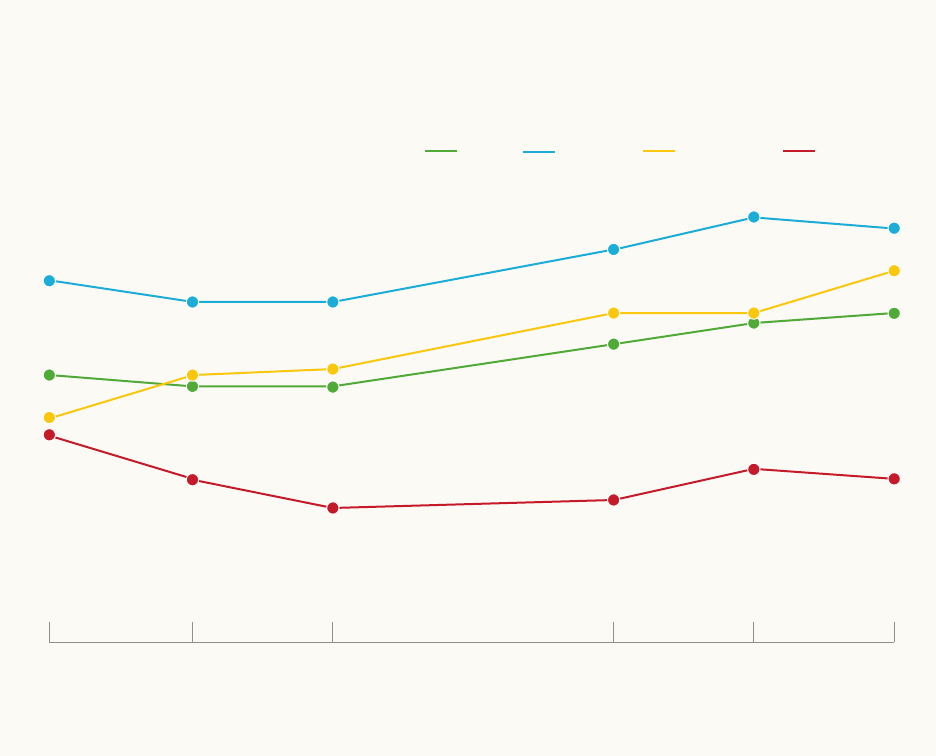

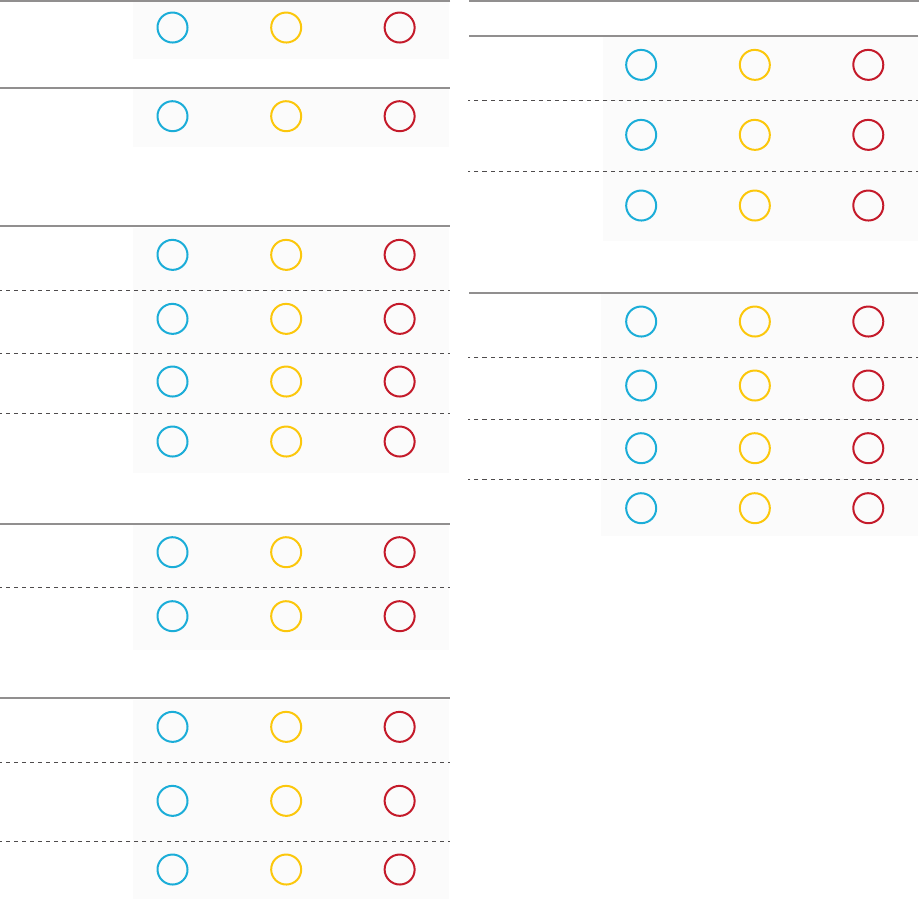

Please indicate how important the following factors are to the United States remaining influential on the

global stage: (%)

n = 1,045

Figure A: Remaining Influential on the Global Stage

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Somewhat important

Very important

Not very important

Promoting democracy and human

rights around the world

Maintaining US economic power

Reducing racial inequality at home

Maintaining US military superiority

Improving public education

Encouraging legal immigration

Reducing economic inequality at home

Increasing public spending on

infrastructure

Preventing political violence such as

the January 6 insurrection

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Strengthening democracy at home

Not important at all

Taking leadership on international

issues

Participating in international

organizations

73 22 3

70 23 4

66 28 4

57 28 9

54 25 9

53 25 11

50 30 11

46 36 10

44 42 9

43 40 12

41 45 10

37 44 13

2

2

4

10

10

8

7

4

5

3

5

1

5

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

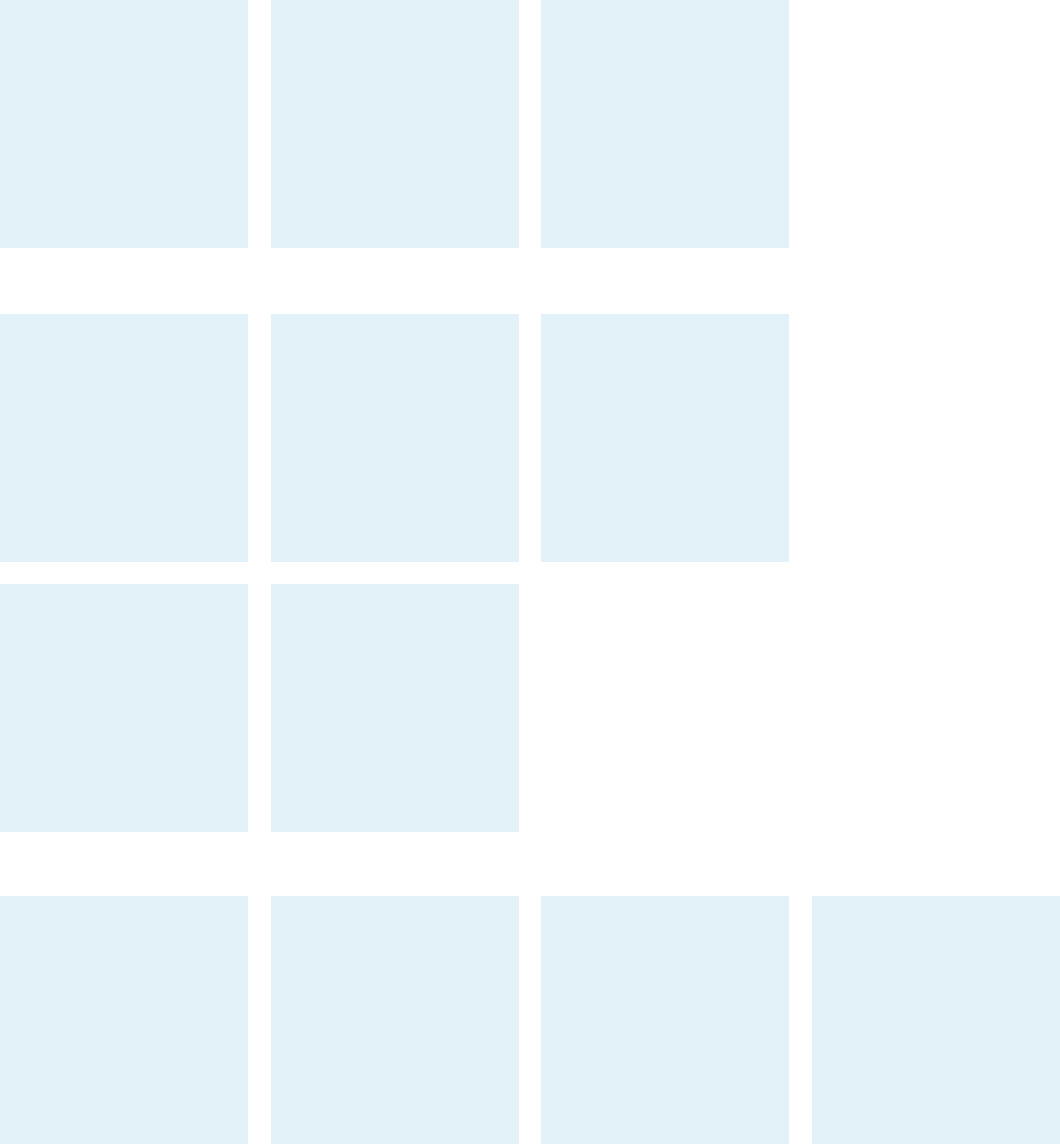

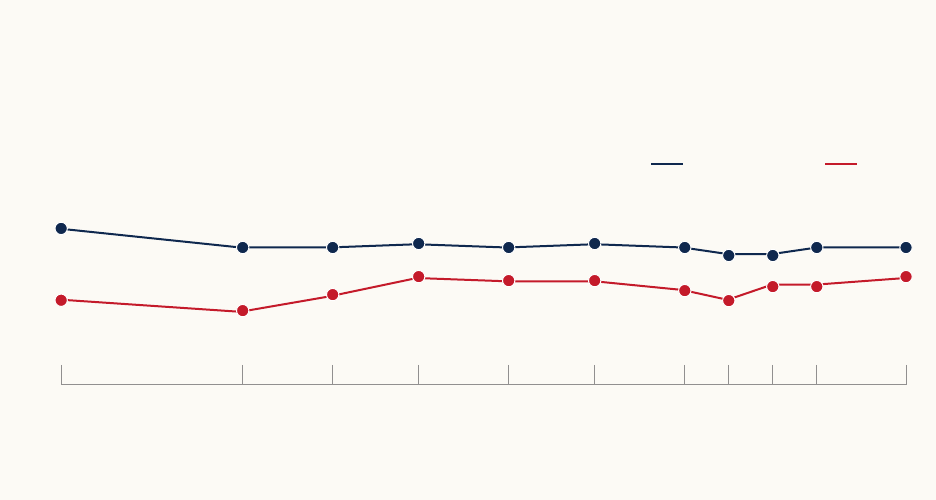

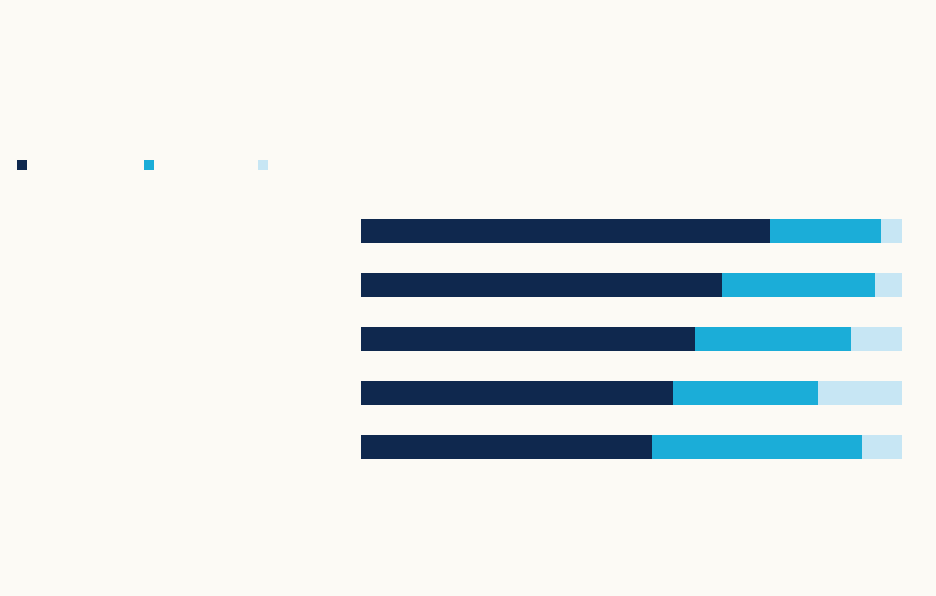

Figure B: US-China Economic Power Comparison

At the present time, which nation do you feel is stronger in terms ofeconomicpower, the United States or

China—or do you think they are about equal economically?(%)

n = 2,086

China

The United States

About equal

26

27

45

2014 2016 2019

2021

28

31

38

29

38

31

31

27

40

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Figure C: US-China Military Comparison

At the present time, which nation do you feel is stronger in terms ofmilitarypower, the United States or

China—or do you think they are about equal militarily? (%)

n = 2,086

China

The United States

About equal

32

54

14

2014 2016 2019

2021

32

50

15

30

58

11

35

46

18

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

6

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Widespread Support for Trade Restrictions against China and

Industrial Policies to Bolster US Businesses

There is a strong economic dimension to the administration’s foreign policy approach, designed, in part,

to increase American competitiveness against China. Many Americans agree, with two-thirds (66%) saying

that maintaining US economic power is one of the most important factors in the United States retaining

global influence. And Americans see China’s rise as a challenge to that economic power.

Americans currently think trade with China has more negatives than positives for the United States.

In a dramatic shift from 2019, a majority of Americans now says trade between the two nations does more

to weaken US national security (58%, up from 33% in 2019). By contrast, two years ago—amid the

US-China trade war—two-thirds of Americans believed that US-China trade strengthened US national

security. And in a separate question, majorities favor increasing taris on products imported from China

(62%) and significantly reducing trade between the two countries, even if this leads to greater costs for

American consumers (57%). A Council poll in March 2021 found that majorities of Americans also favored

prohibiting US companies from selling sensitive high-tech products to China (71%) and prohibiting Chinese

technology companies from building communications networks in the United States (66%).

To compete with China in the development of emerging technologies, US ocials propose direct public

investment into strategically important industries. Americans are broadly supportive of this approach;

eight in 10 say the government should fund research and development of emerging technologies to

give US companies an edge over foreign businesses (79%). Seven in 10 favor financial support for US

companies that are competing against foreign businesses receiving support from their respective

governments (72%).

Slightly fewer Americans—but still majorities—support imposing taris on foreign products in industries

that compete with US businesses (60%), banning or limiting imports from foreign companies that compete

with US businesses (57%), and identifying businesses most likely to succeed and giving them financial

support (55%).

Administration Underestimates Public Support for Trade

Some of the administration’s assumptions about everyday Americans’ inclinations are not borne out by

the data. Administration ocials concede that Americans have not benefited as much from globalization

and US trade policies as much as policymakers had hoped. But the 2021 Chicago Council Survey

suggests these ocials undervalue US public support for globalization and trade.

MORE AMERICANS NOW SAY TRADE BETWEEN

THE UNITED STATES AND CHINA DOES MORE TO

WEAKEN US NATIONAL SECURITY

58%( )

.

7

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

A record number of Americans (68%) now say globalization is mostly good for the United States,

and nearly three-quarters or more consider international trade to be beneficial to consumers, their own

standard of living, US technology companies, the US economy, and US agriculture (Figure D). Smaller

majorities say international trade is good for US manufacturing companies and creating jobs in the United

States. This support for international trade spans the political spectrum.

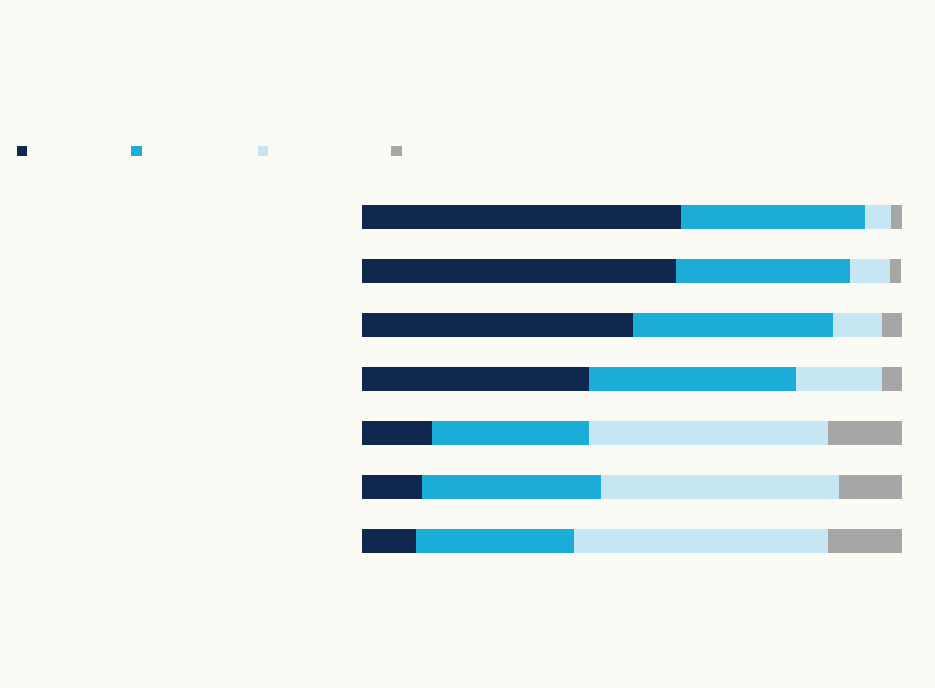

Overall, do you think international trade is good or bad for: (%)

n = 2,086

Figure D: Beneficiaries of Trade

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Bad

Good

US tech companies

US manufacturing companies

The US economy

Consumers like you

Creating jobs in the United States

US agriculture

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Your own standard of living

82

79

78

75

73

63

60

17

20

21

24

25

37

40

(

8

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Solid Support for Continued US Global Leadership

With the recent withdrawal from Afghanistan as a backdrop, there is an enduring assumption among

senior Biden administration ocials that the American public has become disillusioned with the US-led

international order and is ready for a more restrained US foreign policy. As Secretary Blinken said in his

March 2021 speech, “for some time now Americans have been asking tough but fair questions about

what we’re doing, how we’re leading – indeed whether we should be leading at all.”

13

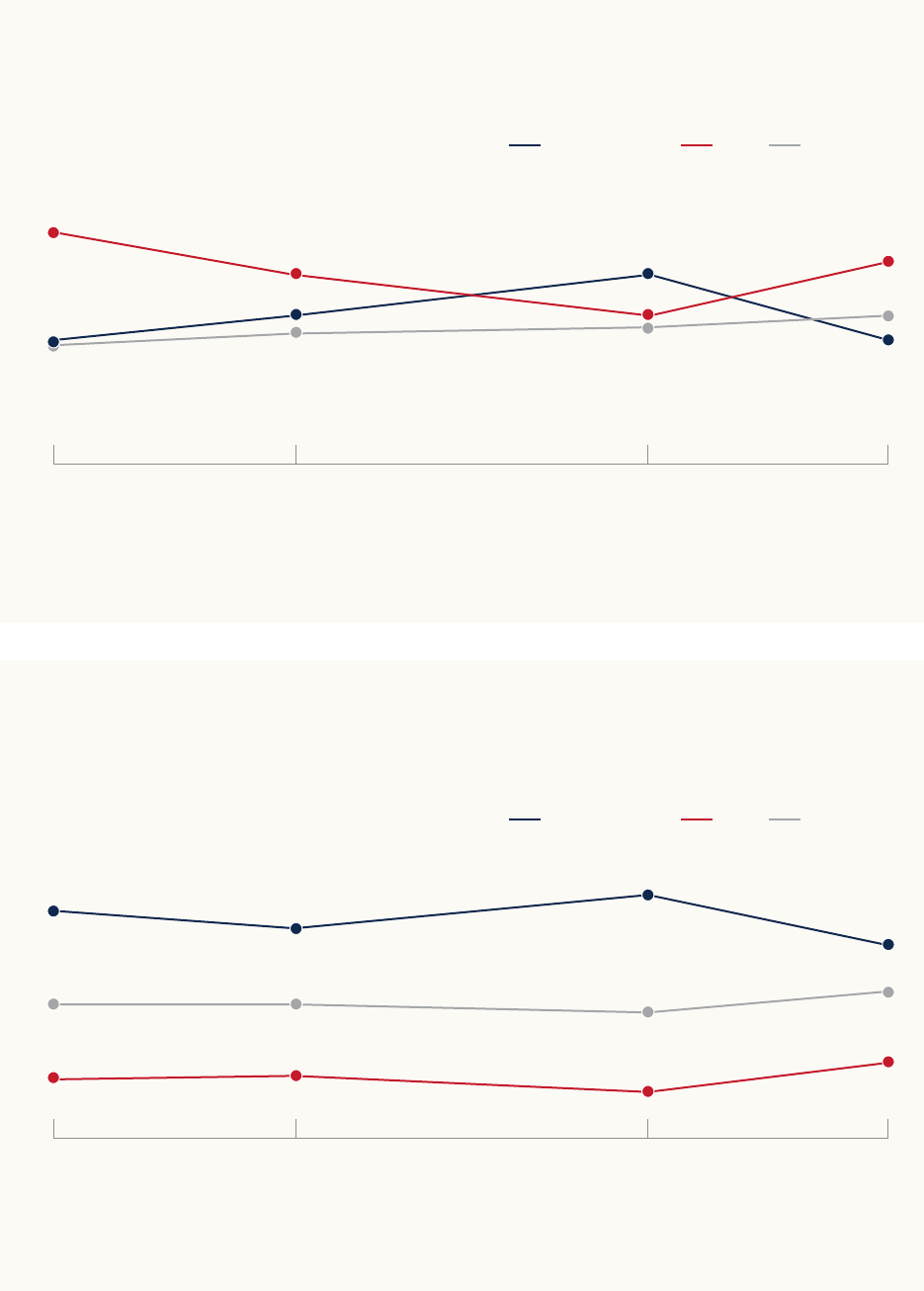

Some of those concerns may be overstated: nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) say it is better for the

United States to play an active part in world aairs than to stay out of world aairs (35%)—a finding that is

consistent with past surveys (Figure E). And a majority of the public believes the benefits of maintaining

the US role in the world outweigh the costs (56%).

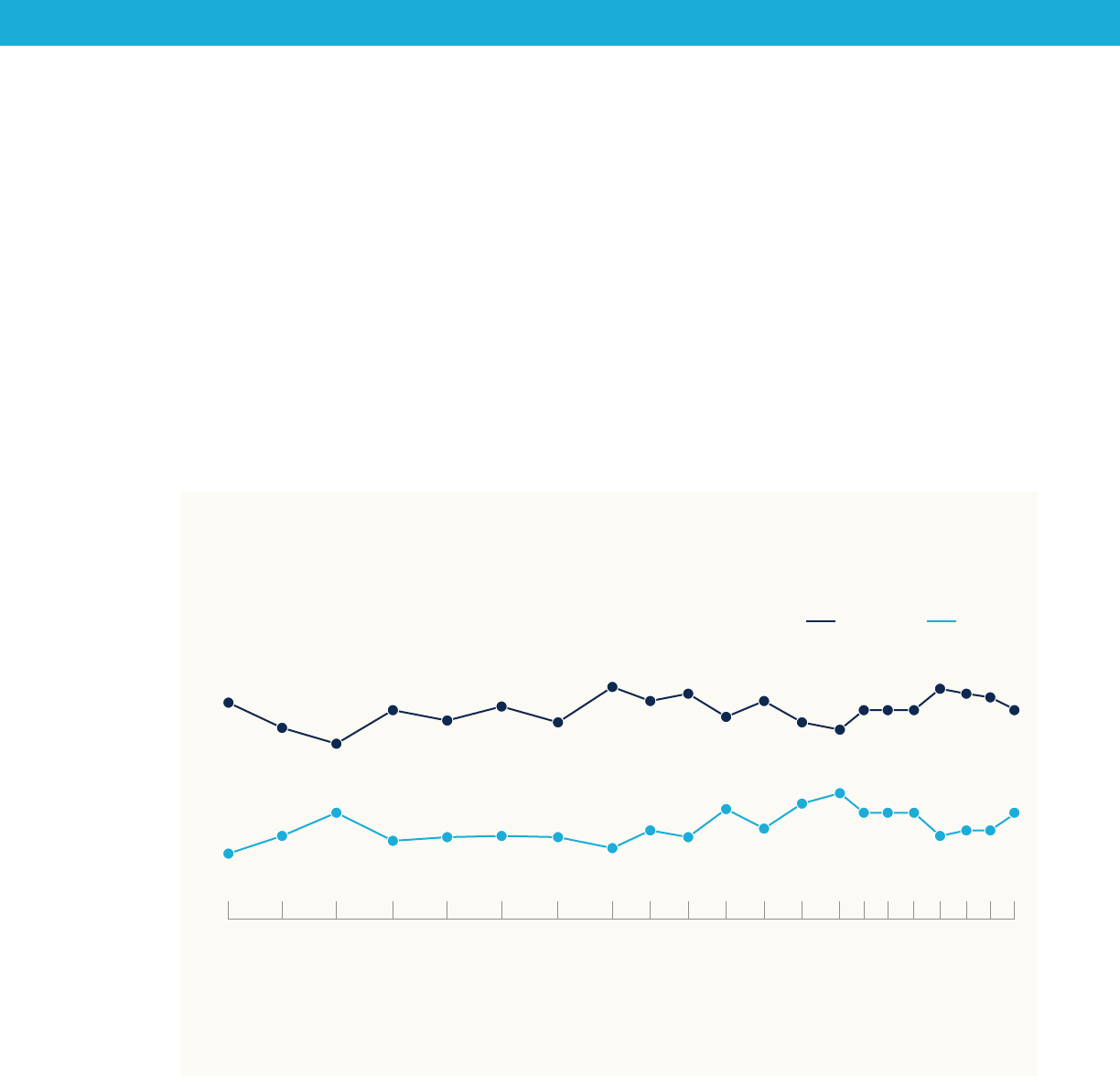

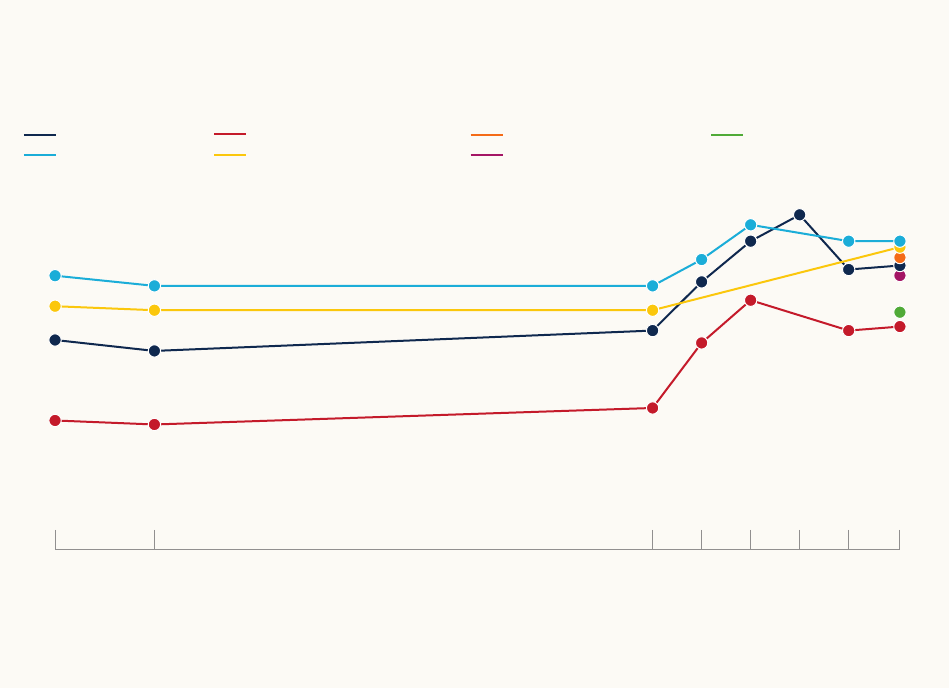

Figure E: US Role in World Aairs

Do you think it will be best for the future of the country if we take an active part in world aairs or if we stay

out of world aairs? (%)

n = 2,086

Active part

Stay out

1978 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002

2004

2006

2008

1974 1982 2010

2012

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

29

23

35

27

28

29

28

25

30

28

36

31

38

41

35

35

35

29

30

30

35

67

59

54

64

62

65

61

71

67

69

63

67

61

58

64

64

64

70

69

68

64

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

9

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

The public also wants the United States to play a leading role in preventing nuclear proliferation (76%),

combating terrorism (67%), sending COVID-19 vaccines to other countries in need (62%), and limiting

climate change (58%). But Americans do not want to manage this responsibility on their own: a large

majority supports a policy of shared leadership (69%) rather than seeking a dominant role for the country

(23%). The public also supports international cooperation in resolving critical global issues, with majorities

of Americans backing US participation in the Paris Agreement on climate change (64%) and the Iran

nuclear agreement (59%).

While Supporting Afghanistan Withdrawal, Americans Still

Want to Rely on US Military

The withdrawal from Afghanistan has prompted fierce criticism of the Biden administration and its

foreign policy approach. But a broad majority of Americans continues to support the decision. Even so,

Americans show little interest in pulling the US military back from other commitments around the world. A

majority of Americans (57%) says maintaining US military superiority is a very important factor to US global

influence, and most think US military bases around the world enhance US military strength. Majorities of

Americans want to either maintain or increase the US military presence in Asia-Pacific (78%), Africa (73%),

Latin America (73%), Europe (71%), and the Middle East (68%).

In addition, Americans are as willing as ever—or even more willing—to send US troops to defend allies

and partners across a range of scenarios. For example, if North Korea invaded South Korea, 63 percent

would support using US troops to defend South Korea. A record-high 59 percent of Americans support

using US troops if Russia invades a NATO ally such as Latvia, Lithuania, or Estonia. Perhaps the most

striking shift is that, for the first time, a bare majority of Americans (52%) supports using US troops if China

were to invade Taiwan; in 2020, only 41 percent supported US involvement.

10

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Conclusion

In a March 2021 speech, Secretary of State Antony Blinken argued that the administration’s priorities

would respond to three questions: “What will our foreign policy mean for American workers and their

families? What do we need to do around the world to make us stronger here at home? And what do we

need to do at home to make us stronger in the world?”

14

As the 2021 Chicago Council Survey shows, this

idea of a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class has some resonance with the American public.

The public believes that reforms to education, democracy, and economic competitiveness will bear

fruit for America’s international role. And, like Biden and many in his administration, Americans are

concerned about the rise of China as an economic and military competitor to the United States. However,

while Americans back reduced trade with China and providing government support for businesses

developing emerging technologies, they are also far more positive about the benefits of trade than the

administration assumes.

Internationally, Americans seek to share leadership with other nations and to establish a leading US role

in addressing many of the world's most pressing challenges, including climate change and the COVID-19

pandemic. They also want the United States to participate in international agreements that address

critical threats, such as the Paris Agreement and the Iran nuclear deal. And though the public backs the

withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan, Americans favor maintaining the existing US military presence

around the world and are more likely now than in past years to support using force to defend US allies

and partners.

The Biden administration’s push to restore American leadership abroad while dramatically renewing

domestic programs contains an internal tension.

15

That tension arises from two key areas. First, senior

administration ocials have only so much time and attention. Focusing on one area, such as global

leadership, will necessarily detract from others, including domestic renewal. More importantly, every

administration has limited fiscal resources and political capital for its initiatives. While the American public

supports revitalization on both domestic and international fronts, the Biden team will inevitably face

trade-os. Ultimately, however, the question will be whether the Foreign Policy for the Middle Class is

able to deliver on both fronts—domestic and international alike—to realize its promised benefits for the

American people.

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Do Americans Think? 2021 Chicago Council Survey

11

DEFINING THE MIDDLE CLASS

A “Foreign Policy for the Middle Class” raises a question: which Americans, exactly, consider themselves

as belonging to the middle class? As other researchers have shown, there are many ways to define the

“middle class.” For this report, we opted to interpret the administration’s use of the term to discuss the

views of Americans overall, rather than focus on Americans who specifically describe themselves as

members of the middle class. This fits with the general rhetorical approach of political figures who often

use “middle class” to mean everyday Americans or the American general public. At any rate, the vast

majority of Americans identifies as some variant of the middle class. When asked what socioeconomic

class they belong in, half of Americans (48%) self-identify as belonging to the middle class; another

quarter (25%) say they are in the lower-middle class, and 18 percent say they are upper-middle class.

Relatively few Americans identify outright as a member of the lower class (8%) or upper class (2%).

That said, the views of those who identify themselves as middle-class Americans do dier from those

of other Americans in some ways, including from both upper-middle-class and lower-middle-class

counterparts.

Some dierences are political. The 48 percent who describe themselves as part of the middle class are

more likely to identify as Republican than lower-class Americans, and less likely to identify as Democrats

compared with upper-class Americans. Middle-class Americans are also more likely than lower-class

Americans to say they are ideologically conservative, and less likely than upper-class Americans to

identify as ideological liberals.

There are also demographic dierences. With an average age of 49, middle-class Americans are

older than the average lower-class American (45) but younger than upper-class Americans (51). They

are also more likely to identify racially as white, non-Hispanic than lower-class Americans. And there

are notable dierences in educational attainment. Lower-class Americans are far less likely to have a

college education, while upper-class Americans are far more likely to say the same. The middle class

sits between these two extremes, with a third holding a college degree, another third with some college

education, and another third with a high school diploma or less.

Some of these dierences also translate into policy preferences. The middle class is more likely than

other Americans to see the United States as the greatest country in the world, and more likely to see US

military superiority as very important to maintaining US influence around the world. They are also more

likely to see controlling and reducing illegal immigration, and limiting China’s influence around the world,

as very important policy goals for the United States. But in many ways, middle-class Americans hold

very middle-of-the-road views. Like other Americans, they favor an active role in the world for the United

States, shared leadership with other countries, and see trade and globalization as largely positive for

the country.

12

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

INTRODUCTION

Not long after US President Joe Biden took oce, his administration announced its overarching foreign

policy strategy—a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class. For President Biden, strengthening the middle

class is an important way to win the “fundamental debate” over whether democracies or autocracies

are the superior system. “We must demonstrate that democracies can still deliver for our people in

this changed world,” he said at the 2021 Virtual Munich Security Conference. “That, in my view, is our

galvanizing mission.”

16

The need to increase American competitiveness in the face of a rising China is a motivating force for this

foreign policy approach. The idea that domestic renewal can revive international influence rests on the

United States simultaneously rebuilding its economy, democracy, and alliances to work “from a position

of strength” worldwide.

The results of the 2021 Chicago Council Survey show that most Americans are receptive to these ideas.

Americans see a need to prioritize domestic revitalization and US competitiveness. There is broad

backing for more restrictive policies toward China, and support for US alliances remains strong. However,

the data also show that the Biden administration—like others before it—underestimates support among

the American public for international trade, US international involvement, and US global leadership. At

the same time, the administration may overestimate the American public’s concern for human rights

and democracy abroad. Despite some critics’ views that the Foreign Policy for the Middle Class is too

expansive with both domestic and international activism, these results show that Americans do not think

US foreign policy should be laid aside while domestic issues are addressed. On the contrary, Americans

expect that domestic improvements will benefit US influence and leadership abroad.

13

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

LINKAGES BETWEEN US DOMESTIC

AND FOREIGN POLICIES

In his inaugural speech, President Biden ticked o a range of challenges aecting the country. “We

face an attack on democracy and on truth. A raging virus. Growing inequity. The sting of systemic racism.

A climate in crisis. America’s role in the world. Any one of these would be enough to challenge us in

profound ways. But the fact is we face them all at once, presenting this nation with the gravest

of responsibilities.”

17

While many of these issues can be viewed from a domestic angle, they also have international

consequences. During his first major foreign policy speech, which he notably directed at the American

people, Secretary of State Antony Blinken made this connection clear, saying “distinctions between

domestic and foreign policy have simply fallen away. Our domestic renewal and our strength in the world

are completely entwined. And how we work will reflect that reality.”

18

Domestic Priorities Rate Highly for Maintaining US Influence

The preference for putting one’s own house in order before—or at the same time as—tackling global

concerns comes through loud and clear in the 2021 Chicago Council Survey.

The public rates improving public education, strengthening democracy at home, and maintaining US

economic power as the top three factors in the United States remaining globally influential (Figure 1).

In addition, maintaining US military superiority, preventing violent attacks such as the January 6

insurrection, and reducing racial and economic inequality all rank higher than taking leadership on

international issues, promoting democracy and human rights around the world, and participating

in international organizations. While some skeptics have criticized the Biden strategy for being too

expansive in its attempts to incorporate domestic issues into its foreign policy, the American public

seems to agree that these issues that have long been considered domestic do, in fact, have a place in

foreign policy conversations.

Greater Concern for Internal Than External Threats

Americans say they are personally more concerned about threats within the United States (81%) than

threats outside the country (19%). This partially reflects a March 2021 survey finding that many Americans

see political polarization (65%), domestic violent extremism (61%), and the COVID-19 pandemic (57%) as

critical threats facing the country. And in a January 2021 Chicago Council poll, more Americans named

violent white nationalist groups in the United States (29%) and China (26%) as the greatest threats to the

country than named terrorist group outside the United States (11%), North Korea (8%), or Iran (2%).

19

14

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

This domestic focus also extends to Americans’ top foreign policy goals, as Figure 2 shows. A large

majority of Americans (79%) say that protecting the jobs of American workers is a very important goal,

in line with the importance they attach to preventing cyberattacks (83%) and nuclear proliferation (75%).

Protecting US jobs, in fact, is seen as more urgent than combating international terrorism (66% very

important), preventing and combating global pandemics (66%), and limiting climate change (54%).

Please indicate how important the following factors are to the United States remaining influential on the

global stage: (%)

n = 1,045

Figure 1: Remaining Influential on the Global Stage

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Somewhat important

Very important

Not very important

Promoting democracy and human

rights around the world

Maintaining US economic power

Reducing racial inequality at home

Maintaining US military superiority

Improving public education

Encouraging legal immigration

Reducing economic inequality at home

Increasing public spending on

infrastructure

Preventing political violence such as

the January 6 insurrection

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Strengthening democracy at home

Not important at all

Taking leadership on international

issues

Participating in international

organizations

73 22 3

70 23 4

66 28 4

57 28 9

54 25 9

53 25 11

50 30 11

46 36 10

44 42 9

43 40 12

41 45 10

37 44 13

2

2

4

10

10

8

7

4

5

3

5

1

15

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Below is a list of possible foreign policy goals that the United States might have. For each one, please

select whether you think that it should be a very important foreign policy goal of the United States, a

somewhat important foreign policy goal, or not an important goal at all: (%)

n = bases vary

Figure 2: Foreign Policy Goals

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Somewhat important

Very important

Not important at all

Combating world hunger

Preventing the spread of

nuclear weapons

Limiting climate change

Combating international terrorism

Preventing cyberattacks

Controlling and reducing illegal

immigration

Improving the United States' standing

in the world

Limiting China’s influence around

the world

Preventing and combating global

pandemics

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Protecting the jobs of US workers

Maintaining superior military

power worldwide

Promoting and defending human

rights in other countries

Protecting weaker nations against

foreign aggression

Helping to bring a democratic form

of government to other nations

83

79

75

66

66

54

53

50

50

50

49

41

32

18

15

1

19 2

23 2

31 3

29 4

27 19

38 9

39 11

43 7

41 9

40 10

50 9

58 9

55 27

16

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Democracy and Human Rights: Focus on Home, Not Abroad

Democracy and human rights have been consistent frames for the Biden administration’s foreign policy

priorities. As Secretary Blinken stated in February 2021, “President Biden is committed to a foreign

policy . . . that is centered on the defense of democracy and the protection of human rights.”

20

Biden himself often frames the challenge of the 21st century as a contest between democracy

and authoritarianism.

However, neither human rights nor promoting democracy abroad is a top foreign policy priority for the

American public. Only four in 10 Americans (41%) see promoting and defending human rights in other

countries as a very important goal for US foreign policy. Even fewer (18%) say that helping to bring a

democratic form of government to other nations is a very important goal for the United States; in fact,

more (27%) say it is not important at all. Furthermore, only a minority of Americans (44%) see promoting

democracy and human rights abroad as a very important factor in maintaining US global influence.

Americans are more concerned about democracy at home. Seven in 10 (70%) say strengthening US

democracy is a very important factor in maintaining US global influence, and 54 percent say the same

about preventing political violence such as the January 6 insurrection. One of the causes of this domestic

focus is that half of Americans (52%) believe American democracy has been temporarily weakened but is

still functioning, while another quarter (25%) see it as permanently weakened. Americans who see their

own democracy as being temporarily or permanently weakened are more likely to focus on strengthening

democracy at home, and they are less likely to see promoting democracy and human rights abroad as a

very important factor in US global influence.

Domestic Spending Priorities

This domestic focus is also amplified in Americans’ views on the federal budget. If forced to make

trade-os between domestic and international priorities, Americans would put most of their money into

domestic spending (Figure 3). When told they have $100 to spend on a hypothetical federal budget,

survey respondents allocate greater average amounts to education ($15.61), healthcare ($15.21), social

security ($14.92), and infrastructure ($13.85) than they do to defense spending ($11.90). Average amounts

are smaller for environmental protection ($9.36), welfare and unemployment programs ($8.07), military

aid ($3.79) and economic assistance ($3.71) abroad, and diplomatic programs to promote US policies

abroad ($3.58).

OF AMERICANS SAY STRENGTHENING US DEMOCRACY IS

VERY IMPORTANT FOR MAINTAINING US INTERNATIONAL

INFLUENCE.

70%

17

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

But these results do not mean that Americans think US foreign policy should be placed on the back

burner while domestic issues are addressed. On the contrary, Americans expect that improvements

on the home front will have knock-on benefits for US influence abroad. In addition, the broad majority

supports continued US involvement in world aairs, continued membership in international organizations,

and continued partnerships with allies and friends—and this is also true for those who prioritize spending

on domestic concerns.

Next, I’d like you to please imagine that you get to choose how to spend $100 of your tax money to make

up the following areas of the US government budget. For each item, please let us know how many dollars

you’d prefer to spend. You must spend all $100: ($)

n = 1,030

Figure 3: US Budget Allocation

2021 Chicago Council Survey

15.61

15.21

14.92

13.85

11.90

9.36

8.07

3.79

3.71

Education

Healthcare

Social security

Improving public infrastructure such

as highways, bridges, and airports

Defense spending

Environmental protection

Welfare and unemployment programs

at home

Military aid to other countries

Economic aid to other countries

Diplomatic programs to promote US

policies abroad

3.58

18

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

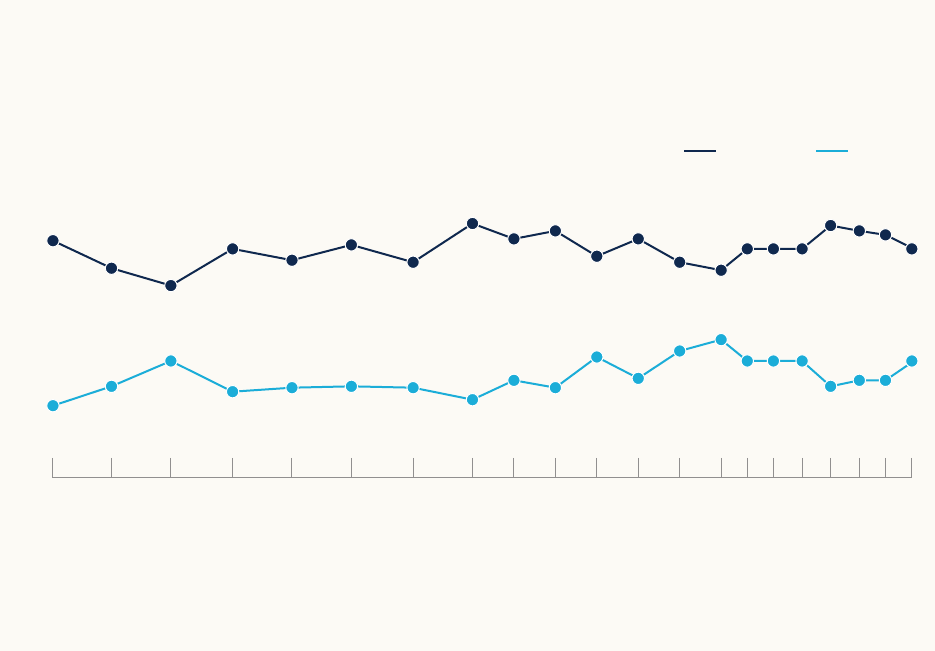

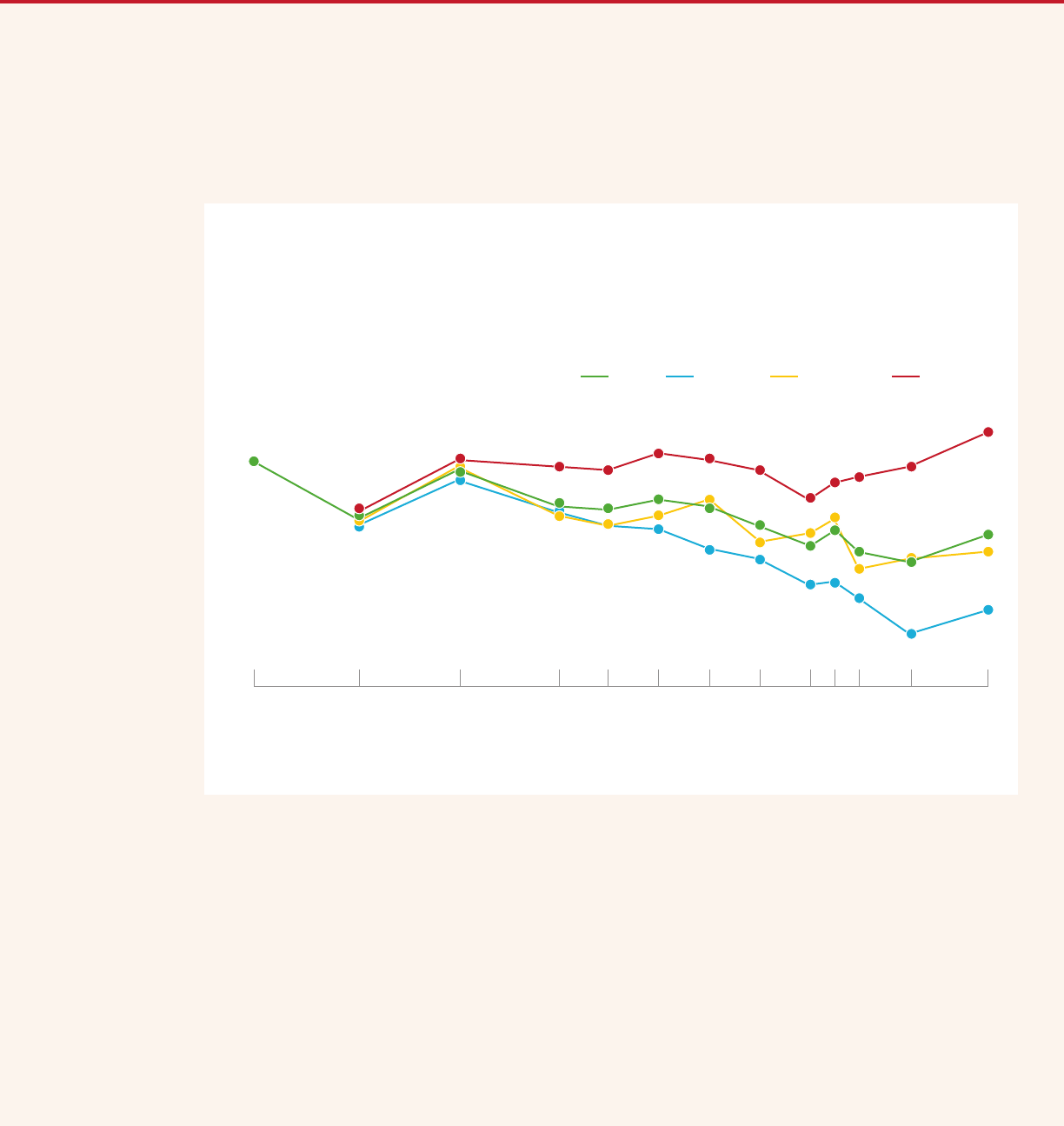

Figure 4: Influence of the United States and China

I would like to know how much influence you think each of the following countries has in the world. Please

answer on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 meaning they are not at all influential and 10 meaning they are extremely

influential. (mean)

n = 1,015

2021 Chicago Council Survey

China

The United States

2002 2006 2016

2021

9.1

8.5 8.5

8.6

8.5

8.6

8.5

8.3 8.3

8.5 8.5

6.8

6.4

6.9

7.5

7.4 7.4

7.1

6.8

7.3 7.3

7.5

2008 2010 2012 2014 2017 2018 2019

BUILDING AT HOME TO COMPETE

WITH CHINA ABROAD

Both on the campaign trail and as president, Biden has been clear that he views China as a competitor

to the United States. As he said in March 2021, “they have an overall goal to become the leading country

in the world, the wealthiest country in the world, and the most powerful country in the world. That’s not

going to happen on my watch.”

21

The 2021 Chicago Council Survey finds that Americans, too, see Chinese

influence growing—and support policies aimed at keeping the United States in the lead.

Americans continue to view the United States as the country with the most influence in the world today,

but their views of China’s influence have shifted over the past 15 years, particularly in 2010 following the

global financial crisis. Today, the gap has closed to one of its narrowest points, with the United States

maintaining a one-point lead in perceived influence over China (Figure 4).

While Americans’ perceptions of US influence have been broadly stable since 2006, more Americans

now (54%) than in 2018 (45%) say the United States is less economically competitive than it was 10 years

ago (27% say it is equally competitive; 19% say it is more competitive). Americans are also notably less

confident now than they were two years ago in both US economic and military strength compared with

China. As Figure 5 shows, a plurality of Americans (40%) say that China is stronger than the United States

economically, up from 31 percent who said the same in 2019; only a quarter (27%) now see the United

States as stronger. And for the first time in Council polling, fewer than half of Americans (46%) see the

United States as stronger than China in terms of military power, down from 58 percent who said the same

in 2019 (Figure 6).

19

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Figure 5: US-China Economic Power Comparison

At the present time, which nation do you feel is stronger in terms ofeconomicpower, the United States or

China—or do you think they are about equal economically?(%)

n = 2,086

China

The United States

About equal

26

27

45

2014 2016 2019

2021

28

31

38

29

38

31

31

27

40

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Figure 6: US-China Military Comparison

At the present time, which nation do you feel is stronger in terms ofmilitarypower, the United States or

China—or do you think they are about equal militarily? (%)

n = 2,086

China

The United States

About equal

32

54

14

2014 2016 2019

2021

32

50

15

30

58

11

35

46

18

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

20

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Support Is Growing for US-China Trade Restrictions

The public’s concern about declining US economic power relative to China is helping to drive support

for policies aimed at reversing that transition. In a dramatic shift from 2019, a majority of Americans now

says trade between the United States and China does more to weaken US national security (58%, up from

33% in 2019), as Figure 7 shows. By contrast, two years ago—amid the US-China trade war—two-thirds of

Americans believed that US-China trade strengthened US national security (64%, now down to 38%).

Does trade between the United States and China do more to strengthen US national security or to weaken

US national security? (%)

n = 2,086

Figure 7: Trade between the United States and China

2021 Chicago Council Survey

More to weaken

More to strengthen

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

64

33

2019

2021

38

58

21

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

There is also growing support for restrictions on trade between the United States and China. A majority

of Americans (62%, up from 55% in 2020) favors increasing taris on products imported from China. Many

(57%, up from 54% in 2020) favor significant reductions in trade between the two countries, even if this

leads to greater costs.

Trade is not the only area of concern in relation to China: technology has been a major area of focus for

the Biden administration. The 2021 Interim National Security Strategy states that the United States must

also “confront unfair and illegal trade practices, cyber theft, and coercive economic practices that hurt

American workers, undercut our advanced and emerging technologies, and seek to erode our strategic

advantage and national competitiveness.”

22

Many Americans, too, are concerned about the technological angle of US-China competition. Half (52%)

favor restricting the exchange of scientific research between the United States and China, and a March

2021 Council poll found that majorities of Americans favored prohibiting US companies from selling

sensitive high-tech products to China (71%) and prohibiting Chinese technology companies from building

communications networks in the United States (66%).

SEE THE UNITED STATES AS STRONGER THAN

CHINA IN TERMS OF MILITARY POWER, DOWN

FROM 58 PERCENT WHO SAID THE SAME IN 2019.

46%

FEWER THAN HALF OF AMERICANS

( )

22

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

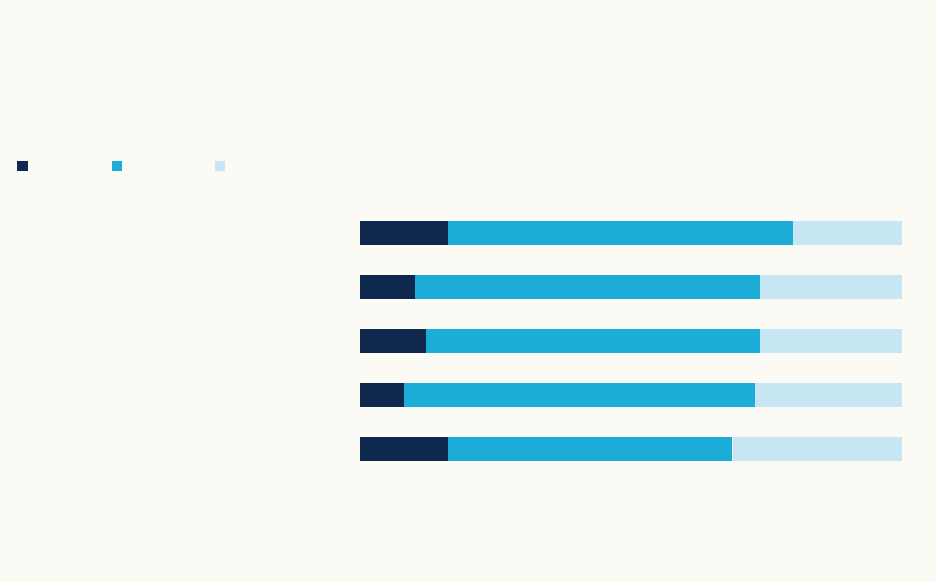

79 18

72 24

60 36

57 39

55 41

Which of the following actions, if any, do you think the US government should take to promote investment

in strategically important industries?(%)

n = 1,071

Figure 8: Promoting Investment in Industry

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Should not take action

Should take action

The US government should impose

taris on foreign products in those

industries that compete with US

businesses

The US government should ban

or limit imports from foreign

companies in those industries that

compete with key US businesses

The US government should fund

research and development of emerging

technologies to give US companies an

edge over foreign businesses in these

new industries

The US government should identify

businesses most likely to succeed in

those industries and oer those

companies financial support

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

The US government should

financially support US companies in key

industries competing against foreign

businesses that receive support from

their own governments

Promoting Strategic Industries

To compete with China in the development of emerging technologies, US ocials propose direct public

investment into strategically important industries. According to a speech delivered on August 9, 2021, by

Secretary Blinken, “there are some things that even the most vibrant private sector can’t do on its own.

Public investment is still vital. Moreover, America’s entrepreneurs are able to do their pathbreaking work

in part because of the foundation provided by public investment.”

23

Majorities of Americans favor the US government investing in strategically important industries. This

support covers a variety of ways in which the federal government could act, though it should be noted

that the question itself did not mention any budget trade-os that would have to be considered before

implementing these policies.

23

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

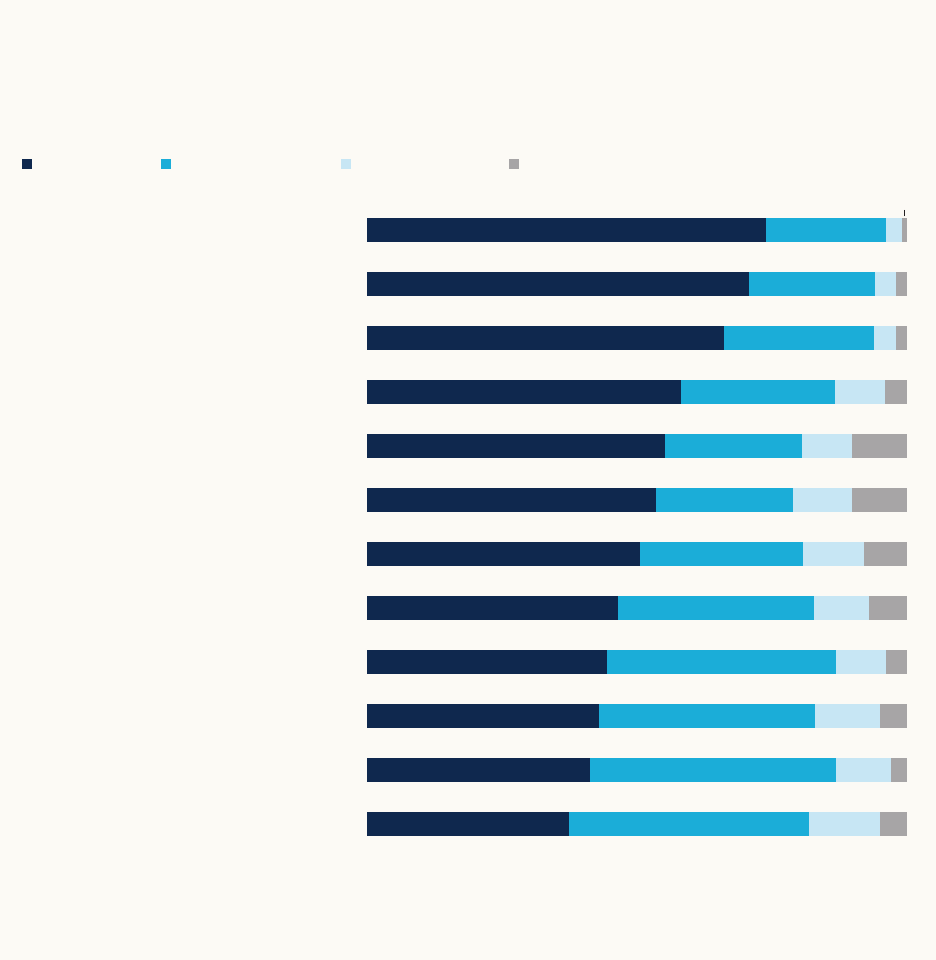

To what extent do the following groups benefit from US foreign policy? (%)

n = 1,053

Figure 9: Beneficiaries of US Foreign Policy

2021 Chicago Council Survey

A fair amount

A great deal

Not very much

Wealthy Americans

Middle-class Americans

The US military

Large companies

Small companies

Working-class Americans

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

The US government

59

58

50

42

13

11

10

34 2

32 7

37 9

38 15

29 44

33 44

29 47

Not at all

5

4

2

4

13

13

12

As Figure 8 shows, eight in 10 Americans say the government should fund research and development of

emerging technologies to give US companies an edge over foreign businesses (79%). Seven in 10 favor

financial support for US companies that are competing against foreign businesses supported by their

respective governments (72%).

Slightly smaller majorities support imposing taris on foreign products in industries that compete with US

businesses (60%), banning or limiting imports from foreign companies that compete with US businesses

(57%), and identifying businesses most likely to succeed and giving them financial support (55%).

Americans Embrace Globalization but Don’t Feel Like Winners

One assumption of the Biden administration that is not borne out by the data is the idea that Americans

have become disillusioned with globalization and trade. This assumption is evident in Secretary Blinken’s

March 3, 2021, speech, “A Foreign Policy for the American People,” in which he noted, “Some of us

previously argued for free trade agreements because we believed Americans would broadly share in

the economic gains that those—and that those deals would shape the global economy in ways that we

wanted. . . . But we didn’t do enough to understand who would be negatively aected and what would

be needed to adequately oset their pain, or to enforce agreements that were already on the books and

help more workers and small businesses fully benefit from them.”

24

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

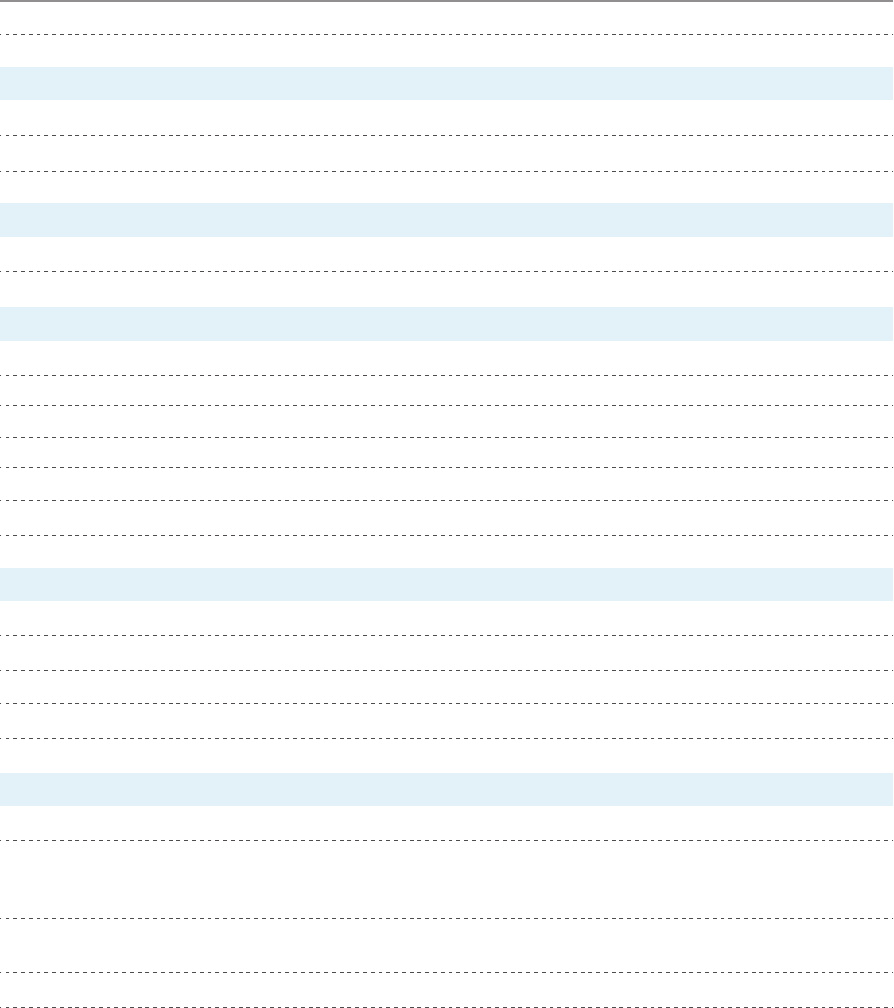

Overall, do you think trade is good or bad for: (%)

n = 2,086

Figure 10: Beneficiaries of Trade

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Your own standards of living

Creating jobs in the US

The US economy

Consumers like you

US agriculture

US technology companies

US manufacturing

companies

2004 2006 202120172016 2018 2019 2020

38

37

40

56

67

59

60

63

73

57

54

59

72

82

87

74

75

78

65

64 64

79

73

70 70

78

85

82

82

The data, reflected in Figure 9, show that the administration is correct that everyday Americans feel

that large companies (92%), the US government (90%), and the wealthy (87%) benefit disproportionately

from US foreign policy decisions. But even those who think the US economic system is unfair to them

personally do not necessarily blame trade policy for this inequality. By nearly a six-to-four margin,

more Americans say the US economic system is personally fair (56%, with 42% saying it is unfair), similar

to 2018 results. When those who think it is unfair are asked which specific factors are to blame, only

27 percent name US trade policy as contributing a great deal. Instead, majorities say that the power of

big business (69%) and the influence of special interests (52%) contribute a great deal to this unfairness,

followed by institutional inequality (41%).

Rather than seeing trade and globalization as sources of unfairness in American life, a record number

of Americans (68%) now say that globalization is mostly good for the United States. As Figure 10 shows,

three-quarters or more consider international trade to be beneficial to consumers like them (82%), their

own standard of living (79%), US technology companies (78%), the US economy (75%), and US agriculture

(73%). Smaller majorities say the international trade has been good for US manufacturing companies (63%)

and creating jobs in the United States (60%).

25

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

International trade agreements have not been a priority for the Biden administration so far, with the

administration and Congress having allowed Trade Promotion Authority to expire in July 2021. The

administration has received ample criticism for refusing to negotiate trade agreements under the rubric of

protecting the middle class, particularly from those in Washington who see automation and innovation as

greater contributors to middle-class job loss than trade.

But the administration’s belief that ordinary Americans oppose trade agreements belies a high level

of public support for both specific and hypothetical trade agreements. Support for the United States–

Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), the renegotiated and renamed North American Free Trade

Agreement (NAFTA), is now at an all-time high (80%). Majorities also support joining the Comprehensive

and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (62%) and a free-trade agreement with

Taiwan (57%).

Build Back Better? Public Doesn't Equate Infrastructure

Rebuild with US Global Influence

The August 2021 passage of the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill in the Senate is a key

component of the Foreign Policy for the Middle Class agenda. It includes the largest federal investment

in infrastructure projects in more than a decade, aecting nearly all aspects of the US economy, including

eorts to limit climate change.

24

Administration ocials have positioned infrastructure investment as a guarantee for future global

economic power and influence, emphasizing that building a strong and modern infrastructure at home

is essential for the United States to push back on Chinese and Russian claims that their economic and

governing systems represent the best path to prosperity.

Americans have been supportive of infrastructure improvement for decades, according to Chicago

Council Surveys. As Figure 3 on page 17 shows, infrastructure rates relatively high on the list of

Americans’ spending priorities. When asked to vote with their hypothetical dollars (given a budget of

$100 total to spend), the public places infrastructure as the fourth most important priority and seems to

favor significant investment ($13.85). This amount is similarly high across all political aliations.

But the data suggest that Americans do not see a link between infrastructure investments and US foreign

policy. As Figure 1 on page 14 demonstrates, the public rates increasing public spending on infrastructure

10th out of 12 factors that would contribute to the US remaining influential on the global stage (ranking

by very important). While larger percentages of respondents see other factors as very important, eight in

10 overall say that infrastructure is at least somewhat important to maintaining US influence (83% very or

somewhat important).

26

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

EFFORTS TO RESTORE US

LEADERSHIP

While key elements of a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class focus on rebuilding at home to project US

influence abroad, returning to the global stage is one of the Biden administration’s top priorities. The

current administration has been careful to temper its language when discussing US leadership. Biden’s

team has emphasized cooperation over unilateral leadership on the world stage.

25

In his September

2021 speech at the UN General Assembly, Biden remarked, "as the United States turns our focus to

the priorities and the regions of the world, like the Indo-Pacific, that are most consequential today and

tomorrow, we’ll do so with our allies and partners, through cooperation at multilateral institutions like

the United Nations, to amplify our collective strength and speed, our progress toward dealing with

these global challenges."

26

This caution is rooted in the belief held by many administration ocials that

Americans outside Washington are no longer supportive of US global leadership and the costs associated

with it.

27

In a 2018 piece for Foreign Aairs, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan attributed this

supposed preference for a restrained foreign policy to the fact that ordinary Americans have not felt the

promised benefit from globalization and the current international order.

28

Despite this, a majority of Americans (64%) continues to say that the United States should take an active

role in world aairs, as they have every year since the Chicago Council first asked this question in 1974

(Figure 11). This is down slightly from 68 percent in 2020 but is in line with the historical average.

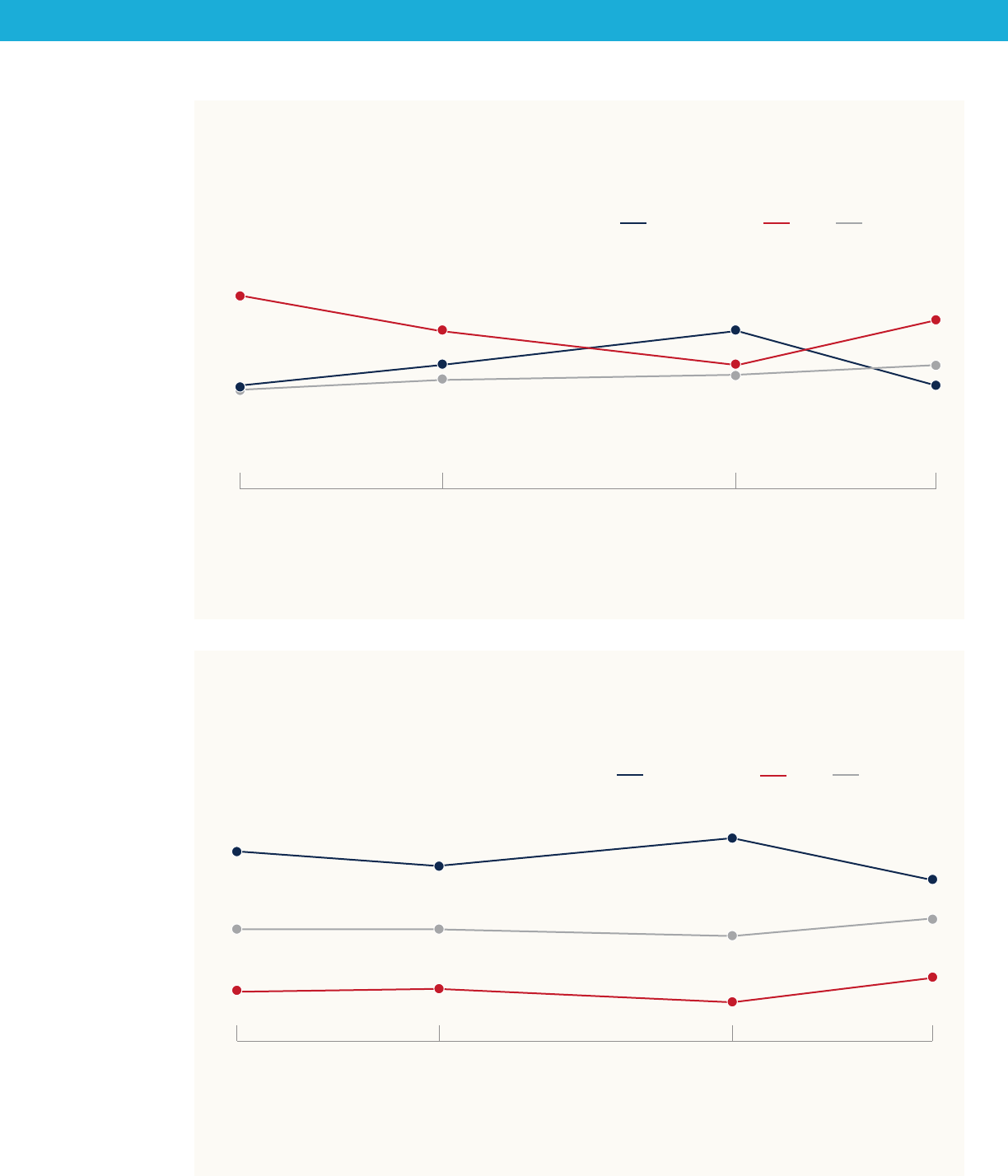

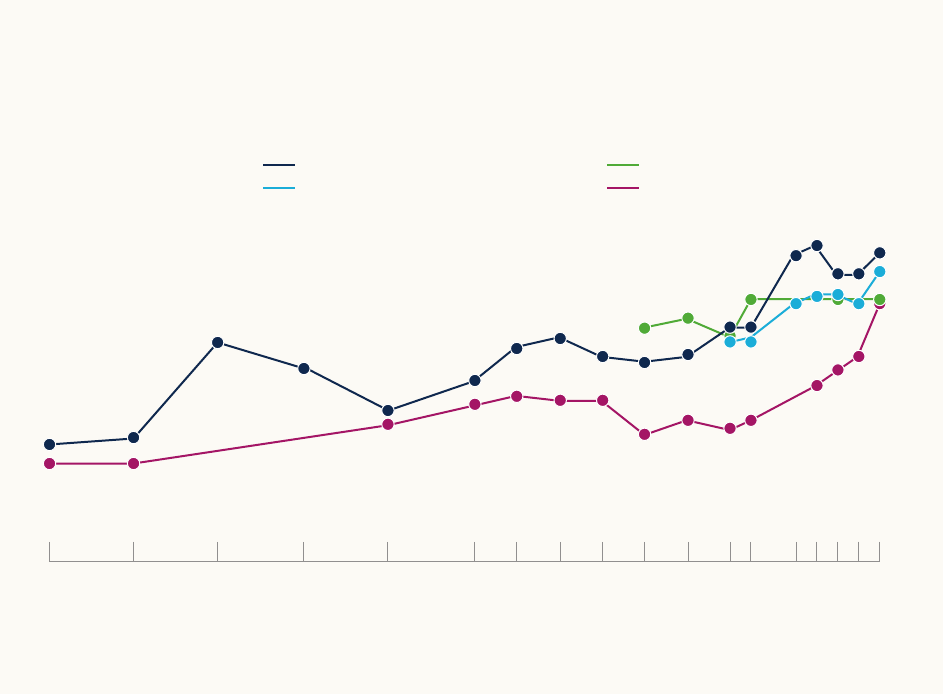

Figure 11: US Role in World Aairs

Do you think it will be best for the future of the country if we take an active part in world aairs or if we stay

out of world aairs? (%)

n = 2,086

Active part

Stay out

1978 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002

2004

2006

2008

1974 1982 2010

2012

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

29

23

35

27

28

29

28

25

30

28

36

31

38

41

35

35

35

29

30

30

35

67

59

54

64

62

65

61

71

67

69

63

67

61

58

64

64

64

70

69

68

64

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

27

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Figure 12: US Leadership Role in the World

What kind of leadership role should the United States play in the world? Should it be the dominant leader,

should it play a shared leadership role, or should it not play any leadership role? (% shared leadership role)

n = 2,086

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Democrat

Republican

Overall

Independent

63

62 62

66

68

69

57

53

50

51

54

53

72

70 70

75

78

77

59

63

64

69 69

73

2015 2016 2017 2019 2020 2021

Moreover, 56 percent say the benefits outweigh the costs of maintaining the US role in the world, down

slightly from 61 percent in 2019.

The data, reflected in Figure 12, also show that a majority of Americans (69%) wants the United States

to play a shared leadership role in the world, as they have since the question was first asked in 2015

(63%). That support crosses partisan lines, with majorities of Democrats (77%), Independents (73%), and

Republicans (53%) all in favor of the United States playing a shared leadership role in the world. Just

23 percent want the United States to be the dominant world leader, and 8 percent want the United States

to play no leadership role at all.

One aspect of support for this shared leadership role is American participation in international

agreements. And the 2021 Chicago Council Survey finds that Americans want the US at the table.

Two-thirds (64%) support US participation in the Paris Agreement on climate change, and 71 percent say

the United States should participate in the International Criminal Court. Six in 10 (59%) Americans think

the United States should participate in the Iran nuclear agreement that lifts some economic sanctions

against Iran in exchange for strict limits on its nuclear program. And on trade, 62 percent think the United

States should sign on to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

28

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Should the United States play a leading role, a minor role, or no role in the following

international eorts?(%)

n = 1,037

Figure 13: US Leadership in International Eorts

2021 Chicago Council Survey

A minor role

A leading role

No role

Sending COVID-19 vaccines to other

countries in need

Limiting climate change

Preventing the spread of nuclear

weapons

Combating world hunger

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Combating international terrorism

76

67

62

58

54

20 3

29 5

29 9

27 14

39 6

The administration has made it clear that it will pursue both American leadership and international

cooperation. In a March 2021 speech, Secretary Blinken noted that, “while the times have changed,

some principles are enduring. . . . One is that American leadership and engagement matter. . . . Another

enduring principle is that we need countries to cooperate, now more than ever.”

29

On specific international eorts, there is majority support for the United States playing a leading role

on preventing the spread of nuclear weapons (76%), combating international terrorism (67%), sending

COVID-19 vaccines to other countries in need (62%), limiting climate change (58%), and combating world

hunger (54%), as Figure 13 shows.

If the United States does not take the lead on these pressing challenges, the American public is skeptical

that other countries will step up. If the United States does not take a leading role on these issues,

few Americans say it is very likely that another country will spearhead eorts on COVID-19 vaccine

distribution (15%), combating world hunger (10%), and limiting climate change (19%).

29

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

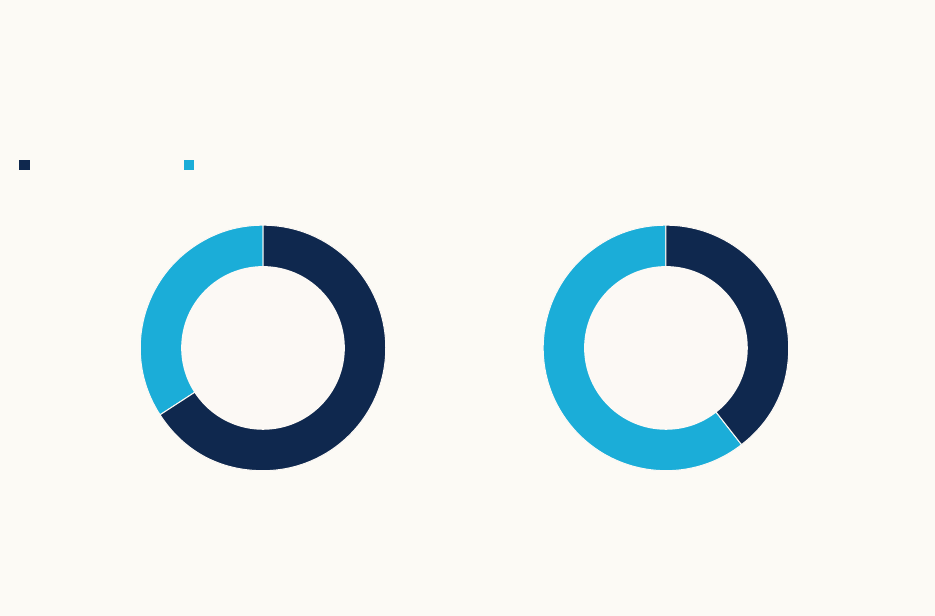

Asia-Pacific

6316 20

Increased

Do you think that the US military presence in the following regions should be increased, maintained at its

present level, or decreased? (%)

n = 2,086

Figure 14: US Global Military Presence

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Maintained

Decreased

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Europe

648 27

Latin America

6310 25

Africa

6112 25

Middle East

5216 30

US MILITARY SUPERIORITY AND

PRESENCE ABROAD

After two decades at war in Afghanistan and 18 years at war in Iraq, there is an enduring assumption that

Americans are weary of “forever wars” and are ready for a more restrained US foreign policy. Secretary

Blinken, who has previously come up for criticism for being too supportive of past military interventions,

30

claimed in January 2019 that whoever won the presidency in 2020 would have to contend with broad

support for retrenchment and an “America First” foreign policy among the American public.

31

But the public-opinion data do not reflect an American public that is ready to withdraw from the

world or that prefers a more restrained foreign policy. A more recent Chicago Council–Ipsos survey

conducted August 23–26 found that two-thirds (64%) of Americans continue to support the US withdrawal

of troops from Afghanistan.

When it comes to the US military, few Americans (15%) want to decrease its size. More than twice as many

want to increase the size of the US military, and a bare majority (52%) wants to keep it about the same

size. In addition, the American public is broadly supportive of the US military presence around the world.

As Figure 14 shows, majorities of Americans want to either maintain or increase the US military presence

in the Asia-Pacific (78%), Latin America (73%), Africa (73%), Europe (71%), and the Middle East (68%).

30

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Do you think the United States uses the following sets of foreign policy tools too much, not enough, or the

right amount?(%)

n = 2,086

Figure 15: US Foreign Policy Tools

2021 Chicago Council Survey

The right amount

Not enough

Too much

Military tools such as drone strikes and

military interventions

Diplomatic tools such as international

agreements, alliances, and participating

in international organizations

Security tools such as defense treaties

and basing US troops abroad

Economic tools such as sanctions and

taris

Note: Figures may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Humanitarian tools such as sharing

vaccines, combating hunger, and

providing disaster relief

42

40

40

38

33

28

28

1545

3128

1645

1749

Not only do Americans support the US military presence around the world but a combined majority of

the public also thinks that defense treaties and basing US troops abroad are used about the right amount

(42%) or not enough (28%), as Figure 15 shows. Just 28 percent say these types of security tools are used

too much in the US foreign policy mix. The data also suggest that a combined majority of the American

public is fairly comfortable using military force. Forty percent say that military tools such as drone strikes

and military interventions are used the right amount, and an additional 28 percent say they are not used

enough. That does not mean that Americans want to rely solely on these tools, however. Pluralities also

say humanitarian tools (45%) and diplomatic tools (45%) are not used enough, and 49 percent say the

same about economic tools such as sanctions and taris.

Of course, maintaining the US military size and presence around the world is not cheap, but the American

public seems largely ready to fund it. When asked to allocate $100 of their tax money to specific areas of

the US budget, respondents apportioned an overall mean of $11.90 for defense spending.

31

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

REVITALIZING ALLIES AND

PARTNERS

Along with domestic renewal of the United States, revitalizing relationships with US allies and partners

has thus far been a core focus of the Biden administration’s foreign policy. “The only way we’re going to

meet these global threats,” President Biden remarked after a G7 meeting, “is by working together, and

with our partners and our allies.”

32

In a March 2021 speech, Secretary Blinken called allies a “unique asset”

and said the administration is “making a big push right now to reconnect with our friends and allies, and to

reinvent partnerships that were built years ago so they’re suited to today’s and tomorrow’s challenges.”

33

The idea that alliances benefit the United States was called into question under the Trump administration.

But the American public did not see US allies as free riders. Instead, the 2020 Chicago Council Survey

found that majorities of Americans said alliances benefited both the United States and its allies in East

Asia (59%), Europe (67%), and the Middle East (61%). And in 2020, seven in 10 Americans (71%) said the

United States should be more willing to make decisions with its allies even if this means the United States

may not get its preferred policy choice.

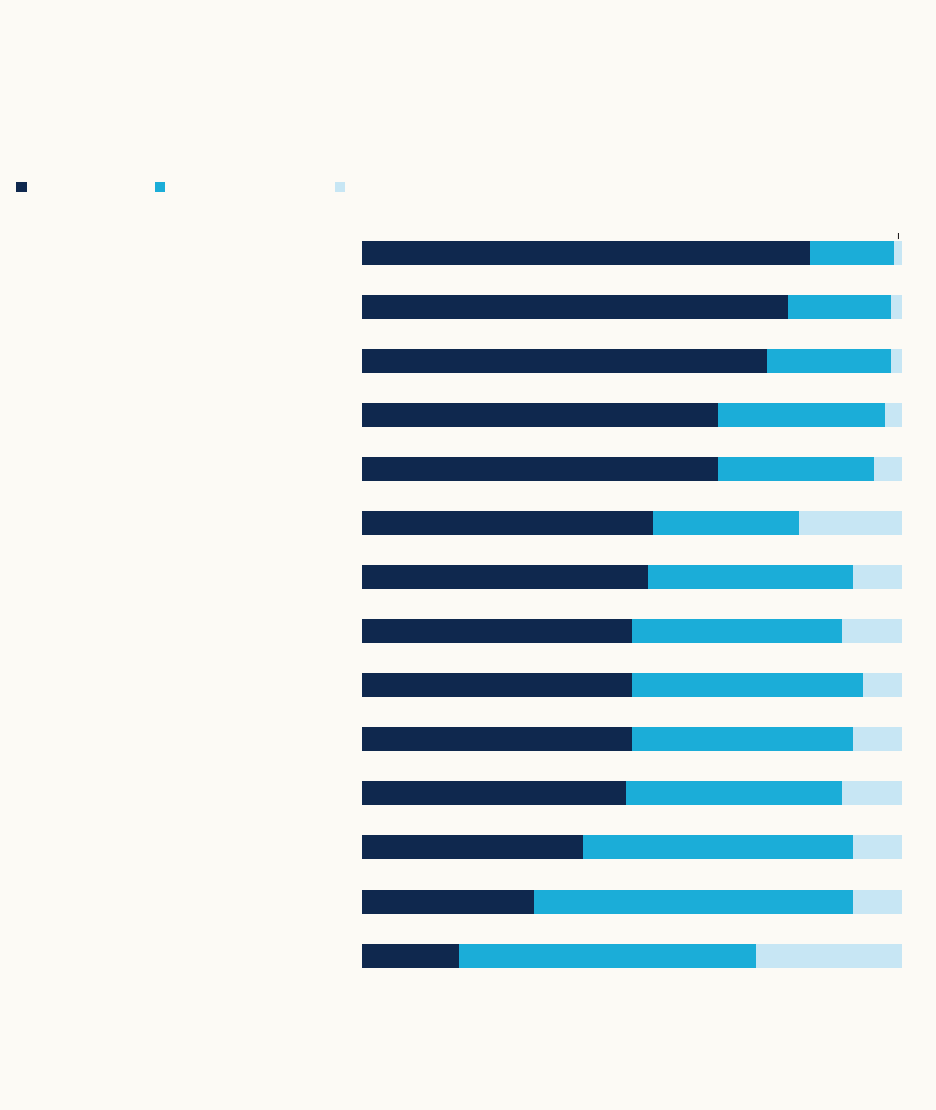

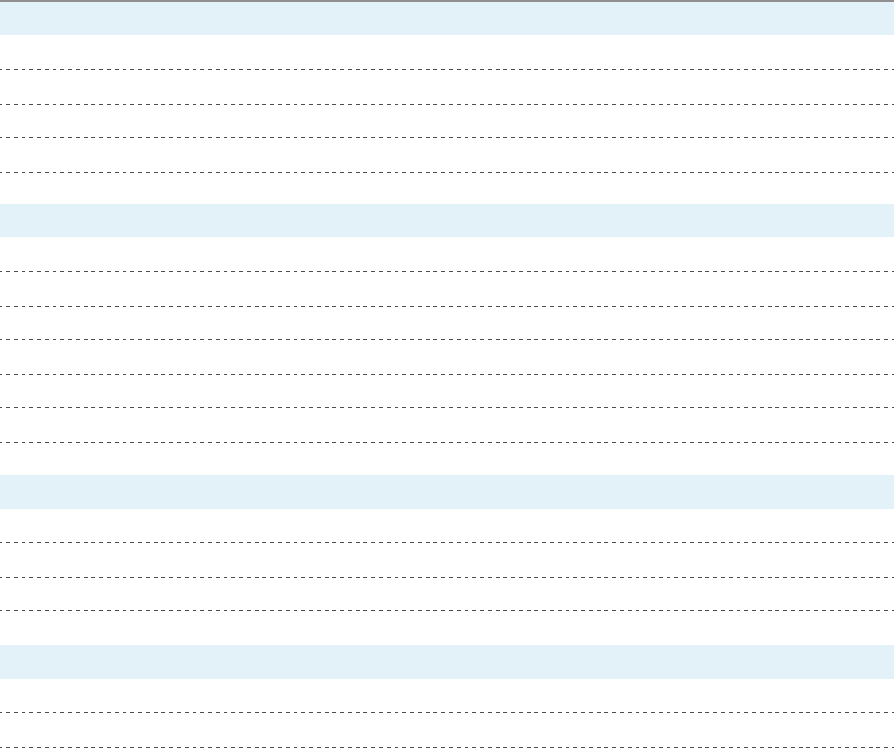

Figure 16: Use of US Troops Abroad

There has been some discussion about the circumstances that might justify using US troops in other parts of

the world. Please give your opinion about some situations. Would youfavoror oppose the use of US troops:

(% favor)

n varies

2021 Chicago Council Survey

If China invadedTaiwan

If Israel were attacked by its neighborsIf North Korea invaded South Korea

If Russia invades a NATO ally like Latvia,

Lithuania, or Estonia

1990 1994 1998 2008

2015

20212002 2004 2006 2010 2012 2014

2018

2017 2019

2020

44

47

44

27

63

53

59

52

19861982

19

24

19

22

39

30

31

36

33

43

32

45

32

41

25

40

49

28

41

45

26

47

45

53

28

47

62

64

5858

52

54

54

52

53

35

38

41

32

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Of course, a core element of US alliances is the security guarantee to use the US military in the case

an ally is attacked by a foreign power. Across a range of scenarios, American public support to use US

military force to defend allies or partners either remains stable or has increased (Figure 16). For example,

if North Korea invaded South Korea, 63 percent would support using US troops to defend South Korea.

That is up from 58 percent in 2020 and only one percentage point lower than the all-time high of 64

percent in 2018. A record-high 59 percent of Americans support using US troops if Russia invades a

NATO ally such as Latvia, Lithuania, or Estonia. That is up from 52 percent in 2020 and the previous high

of 54 percent in 2019. Just over half of Americans (53%) continue to say that they would favor using US

troops to defend Israel if it is attacked by its neighbors. Perhaps the most striking shift is that, for the

first time, a majority of Americans (52%) supports using US troops if China invaded Taiwan. In 2020, that

number was 41 percent.

THE MISSING LINK: MANY AMERICANS NOT YET

CONVINCED IMMIGRATION ADDS TO US GLOBAL

INFLUENCE

SIDEBAR

Secretary Blinken frequently emphasizes the edge

immigrants provide to the United States in the global

economy and the importance of incentivizing the

“best and brightest” people to come live, study, and

work in the United States when speaking about

domestic renewal.

The 2021 Chicago Council Survey data show the

anti-immigrant rhetoric amplified by former

President Trump, other public figures, and certain

media outlets in recent years is not widely shared

among the American public. Majorities of Americans

express net favorable views of Korean (77%),

Chinese (70%), and Mexican immigrants (69%).

Despite these generally favorable views of

immigrants, however, Americans overall are less

convinced than the current administration that

encouraging legal immigration should be a priority

when it comes to ensuring our continued global

influence. When asked how important several

dierent factors are for the United States to remain

influential on the global stage, only 46 percent of

Americans classify encouraging legal immigration as

a very important factor (see Figure 1 on page 14).

Immigration is one of the issues over which

Americans remain most divided in terms of overall

results and especially across partisan aliation. Half

of Americans see controlling and reducing illegal

immigration as a very important foreign policy goal.

The gap between Republicans’ and Democrats’

views on this issue have widened tremendously

since 1998, when they were separated by only four

percentage points as opposed to the 54 percentage

points that separate them today (Figure 17).

33

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Figure 17: Foreign Policy Goals: Controlling Illegal Immigration

Below is a list of possible foreign policy goals that the United States might have. For each one, please select

whether you think that it should be a very important foreign policy goal of the United States, a somewhat

important foreign policy goal, or not an important goal at all:Controlling and reducing illegal immigration

(% very important)

n = 1,492

2021 Chicago Council Survey

Democrat

Republican

Overall

Independent

72

1994 1998 2002 2010

2015

20212004 2006 2008 2012 2014 2016 2018

55

57

53

54

50

81

27

45

70

73

67

71

59

71

57

56

58

70

53

53

61

75

52

56 59

73

46

61

53

70

43

48

61

66

68

71

47

52

45

42

50

55

40

43

35

36

31

20

THE MISSING LINK: MANY AMERICANS NOT YET

CONVINCED IMMIGRATION ADDS TO US GLOBAL

INFLUENCE (CONTINUED)

SIDEBAR

The Biden administration’s proposed immigration

reform legislation, known as the US Citizenship

Act, lays out an eight-year path to citizenship for

many of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in

the United States today. A majority of Americans

thinks illegal immigrants should be allowed to stay

in their jobs and apply for US citizenship either

with conditions (24%) or without (41%). But there is a

stark partisan divide on this question, likely making

major immigration reform a tough sell for the Biden

administration at this time.

34

A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class—What Americans Think 2021 Chicago Council Survey

CONCLUSION

As the president wrote in the 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, “America is back.

Diplomacy is back. Alliances are back.” Do the American people believe that America is back? And do