Soft Power in Asia:

Results of a 2008 Multinational

Survey of Public Opinion

Christopher B. Whitney, Project Director

David Shambaugh, Senior Project Consultant

New Results and Analysis

2009 Edition

In Partnership with

New Results and Analysis

2009 Edition

Soft Power in Asia:

Results of a 2008 Multinational

Survey of Public Opinion

Christopher B. Whitney, Project Director

David Shambaugh, Senior Project Consultant

In partnership with

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs is a leading, independent nonpartisan organization committed to

influencing the discourse on global issues through contributions to opinion and policy formation, leadership

dialogue, and public learning.

The Chicago Council provides members, specialized groups, and the general public with a forum for the

consideration of significant international issues and their bearing on American foreign policy.

THE CHICAGO COUNCIL TAKES NO INSTITUTIONAL POSITION ON POLICY ISSUES AND HAS NO

AFFILIATION WITH THE U.S. GOVERNMENT. ALL STATEMENTS OF FACT AND EXPRESSIONS OF OPINION

CONTAINED IN ALL ITS PUBLICATIONS ARE THE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AUTHOR OR AUTHORS.

Copyright © 2009 by The Chicago Council on Global Affairs

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

This report may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by sections

107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and excerpts by reviewers for the public press), without written permission

from the publisher. For further information about The Chicago Council or this study, please write to The Chicago

Council on Global Affairs, 332 South Michigan Avenue, Suite 1100, Chicago, IL, 60604, or visit the Chicago

Council’s Web site at www.thechicagocouncil.org.

Table of Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Section I: Attitudes Towards Economic Cooperation and Security in Asia . . . . . . . 3

Economic Integration ...................................................3

Regional Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Section II: Soft Power . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Overall Soft Power Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Section III: Perceptions of Individual Countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Perceptions of the United States ........................................ 11

Perceptions of China . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Perceptions of Japan ...................................................18

Perceptions of South Korea .............................................20

Section IV: Bilateral Perceptions ............................................23

China–United States ...................................................23

United States–Japan ...................................................26

China–Japan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28

Japan–South Korea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

Conclusion ................................................................34

Appendix A: Soft Power Indices .............................................35

Questions included for each index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36

Appendix B: Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Appendix C: Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

1ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Asia is in flux. Although ostensibly peaceful, rela-

tions between Asian states are changing rapidly. In

recent years Asian economies have posted world-

best growth statistics (although they have been

severely hit by the economic downturn, especially

since the onset of the international financial cri-

sis in September 2008). Regional interdependen-

cies are binding economies and societies together

like never before. Multilateral mechanisms are

growing, and intergovernmental cooperation has

reached new levels. While terrorism is a persistent

problem in Southeast Asia, no interstate or intra-

state wars rage in the region. Conflict around the

normally volatile Tawain Strait has been notably

muted. Previous hostilities have been quieted and

relations among former adversaries normalized.

Yet beneath the surface, suspicions and ten-

sions among societies are evident. Historical

memory has not been erased between longtime

regional adversaries. The rise of China is reshap-

ing the strategic map.

1

Japan’s former Prime

Minister Yasuo Fukuda’s “Asia First” policy indi-

cated a desire for his country to reengage on the

regional stage. The Association of Southeast Asian

Nations (ASEAN) gained a new level of confidence

1. See Evan S. Medeiros et al, Pacific Currents: The Responses

of U.S. Allies and Security Partners in East Asia to China’s

Rise (Santa Monica: The Rand Corporation, 2008); David

Shambaugh, Power Shift: China & Asia’s New Dynamics

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005); Robert

Sutter, China’s Rise in Asia: Promises and Perils (Lanham,

MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005); Kokubun Ryosei and Wang

Jisi, eds., The Rise of China and a Changing East Asian Order

(Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange, 2004).

and regional engagement after celebrating its for-

tieth anniversary and promulgating a new char-

ter. Beyond shifting power, regional “hotspots”

like North Korea and the “black spot” of Myanmar

fester and continue to threaten regional stability.

Globalization and nontraditional security con-

cerns affect all countries in the region.

The region is also experiencing a shift in

power, both in terms of U.S.-China relations

and key regional relationships. The emergence

of China as a major power has strengthened the

region’s role as a global economic engine and

altered the regional balance of power. While the

United States remains the leading military power

in Asia and the region’s primary export market,

some have questioned its reliability, responsibil-

ity, and continued military presence in the region.

China has used its growing economic power,

increased East Asian economic interdependence,

and skillful diplomacy to co-opt the interests of

its neighbors and assert its influence. As a result

of these and other developments, East Asia as

a region is facing a new political task of finding

ways to reduce tensions, misunderstandings,

and misinterpretations prevalent in any period of

power shift and transition.

To better understand the power shift and the

U.S. role compared to China and other regional

actors, The Chicago Council on Global Affairs and

the East Asia Institute (EAI) surveyed people in six

countries—China, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam,

Introduction

2 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Indonesia, and the United States—in the first half

of 2008 about regional security and economic

integration in Asia and about how these nations

perceive each other. In a new era of interconnect-

edness and growing interdependencies, the goal

was to examine Asian perceptions of these six

nations’ “soft power” in the region. Which coun-

try has the most soft power, or ability to achieve its

goals through “attraction rather than coercion or

payments” (Nye 2005)?

2

How do citizens of these

nations view each other’s popular culture, com-

mercial prowess and brands, intellectual influence,

diplomatic reputations, and political systems?

This report aims to outline trends in the current

and potential use of soft power in East Asia.

The surveys included more than forty ques-

tions in each country and were completed prior to

the global economic downturn during the second

half of 2008. The Council published initial findings

in its 2008 report Soft Power in Asia. This report

presents the project’s complete findings.

The findings were unexpected. The responses

directly called into question the conventional

wisdom that China was chipping into, if not over-

shadowing, U.S. soft power and showed that the

United States continues to wield considerable soft

power in the region.

Section one of this report deals with attitudes

towards economic integration and regional secu-

rity in East Asia. Section two analyzes the impli-

cations of the survey results for soft power in the

region. Section three examines the perceptions of

the surveyed countries towards one another, and

section four analyzes four important bilateral rela-

tionships: U.S.–China, U.S.–Japan, China–Japan,

and Japan–South Korea.

2. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in

World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004).

3ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Economic Integration

Intraregional interactions at all levels have signifi-

cantly intensified across East Asia in recent years.

All major trading states in East Asia now engage in

greater intraregional trade than with other parts of

the world. East Asia is the world’s largest regional

recipient of foreign direct investment, and the vast

majority of it originates in the region. Deep eco-

nomic interdependencies have developed along-

side increases in trade and investment. Dramatic

rises in intraregional tourism, student and cul-

tural exchanges, professional interactions, and

electronic communications have supplemented

economic connections. Intraregional diplomacy

is also intensive. Leaders and government offi-

cials constantly tour the region to strengthen

bilateral ties. In addition, multilateral institu-

tions and groupings have proliferated across Asia

in recent years, creating an institutional archi-

tecture of overlapping organizations. While East

Asia has nowhere near the institutionalized level

of pan-regional cooperation as Europe, Asian

multilateralism is following its own path and is

developing rapidly.

These connections among Asian societ-

ies have multiplied with remarkable speed and

intensity over the past decade. But are they lead-

ing to greater regionalism and regional identities?

Are these interconnections doing for Asia what

occurred in Europe in the 1990s?

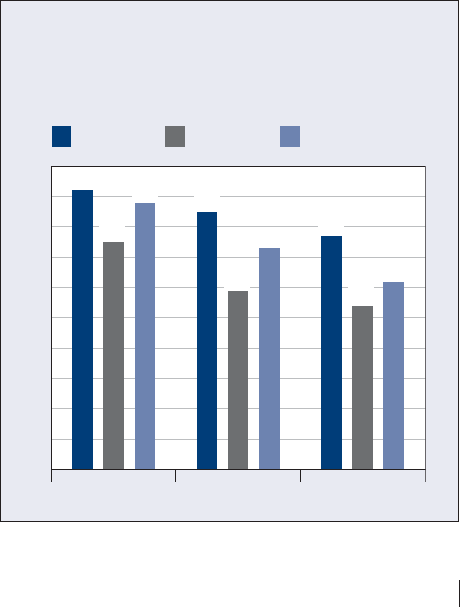

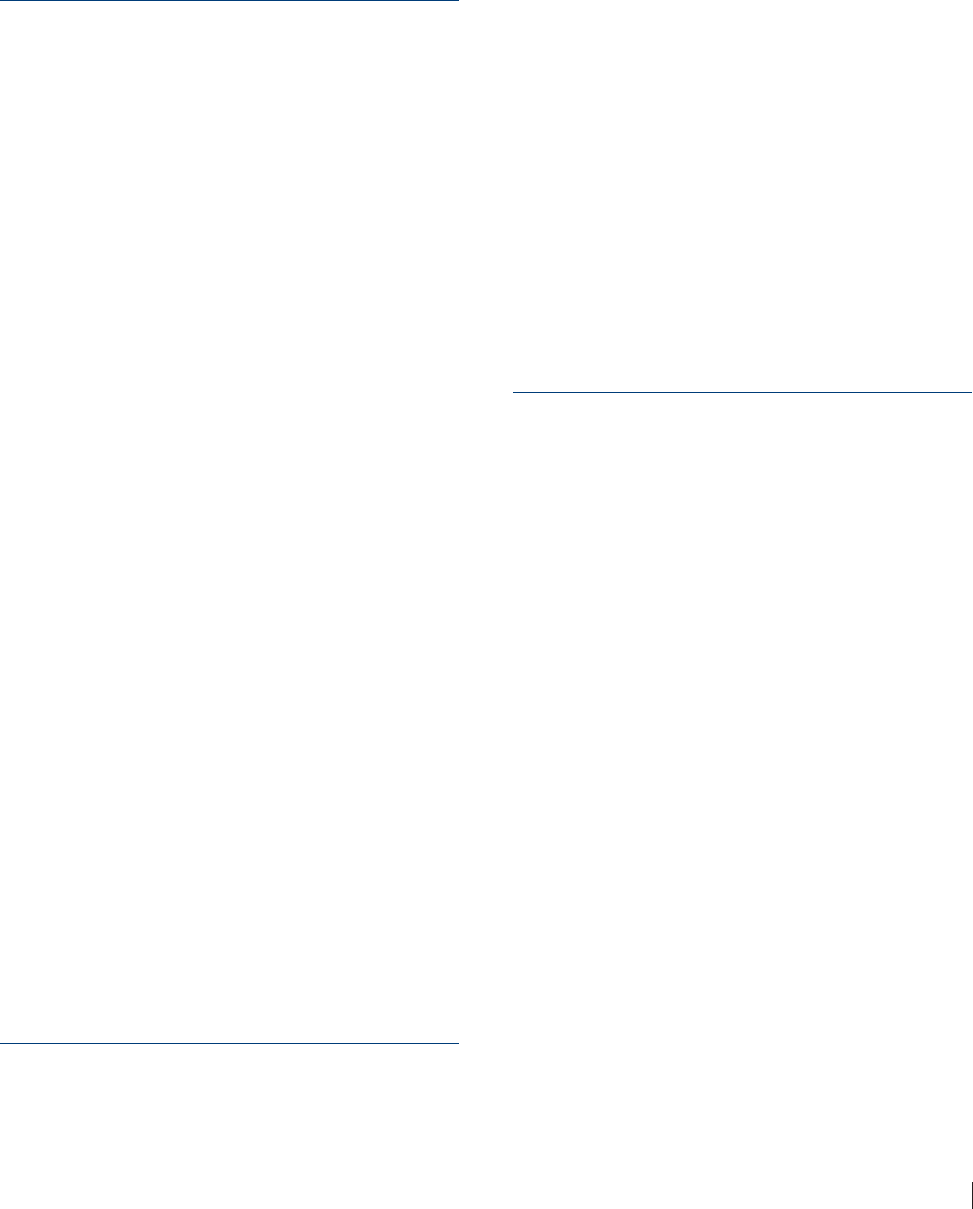

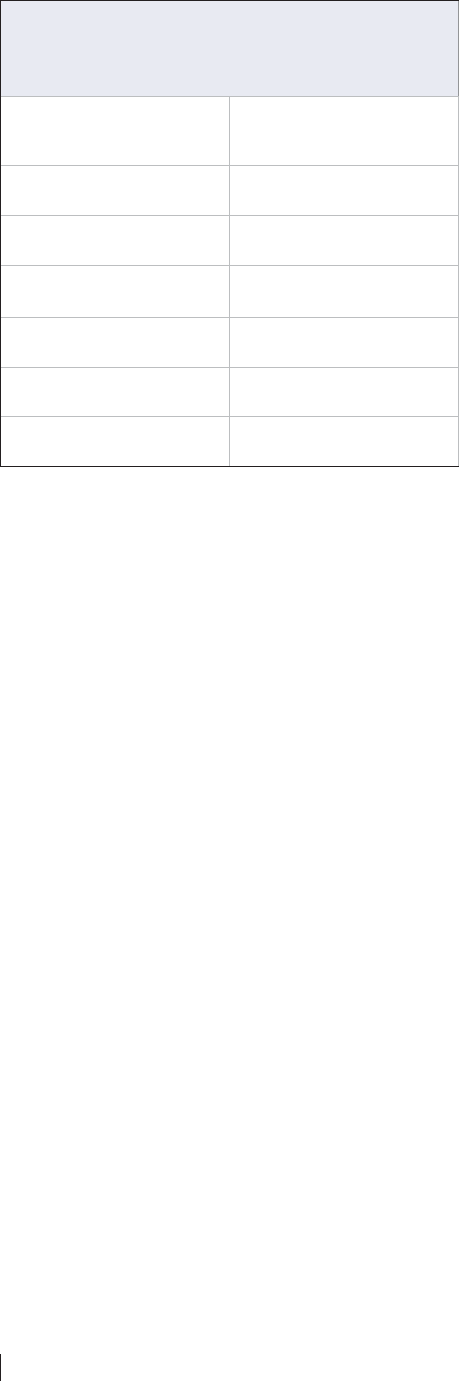

On the question of identity, respondents in

China and South Korea—and to a lesser extent

Japan—tend to view themselves less as either

“East Asian” or “Asian” than as their own nation-

ality (see Figure 1). On separate 0 to 10 scales ask-

ing how much a respondent thinks of himself or

herself as the country’s nationality, East Asian,

or Asian, Japanese, Chinese, and South Koreans

identify most closely with their own countries

(averaging 7.5, 9.2, and 8.8, respectively, on the

scale). While these same citizens see themselves

less as East Asians (5.4, 7.7, and 6.2, respectively)

Section I: Attitudes Towards Economic Cooperation and

Security in Asia

Figure 1 – Identity

Average rating by respondents in each country on how

much they think of themselves as the following

(0 to 10 scale).

9.2

7.5

8.8

8.5

5.9

7.3

7.7

5.4

6.2

Own nationality Asian East Asian

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

China Japan South Korea

4 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

and Asians (5.9, 8.5, and 7.3, respectively), these

ratings are not low. This indicates that there is def-

initely some identification with the greater region

beyond national borders. Thus, as in Europe, there

is evidence that Asians simultaneously think of

themselves in both national and regional terms.

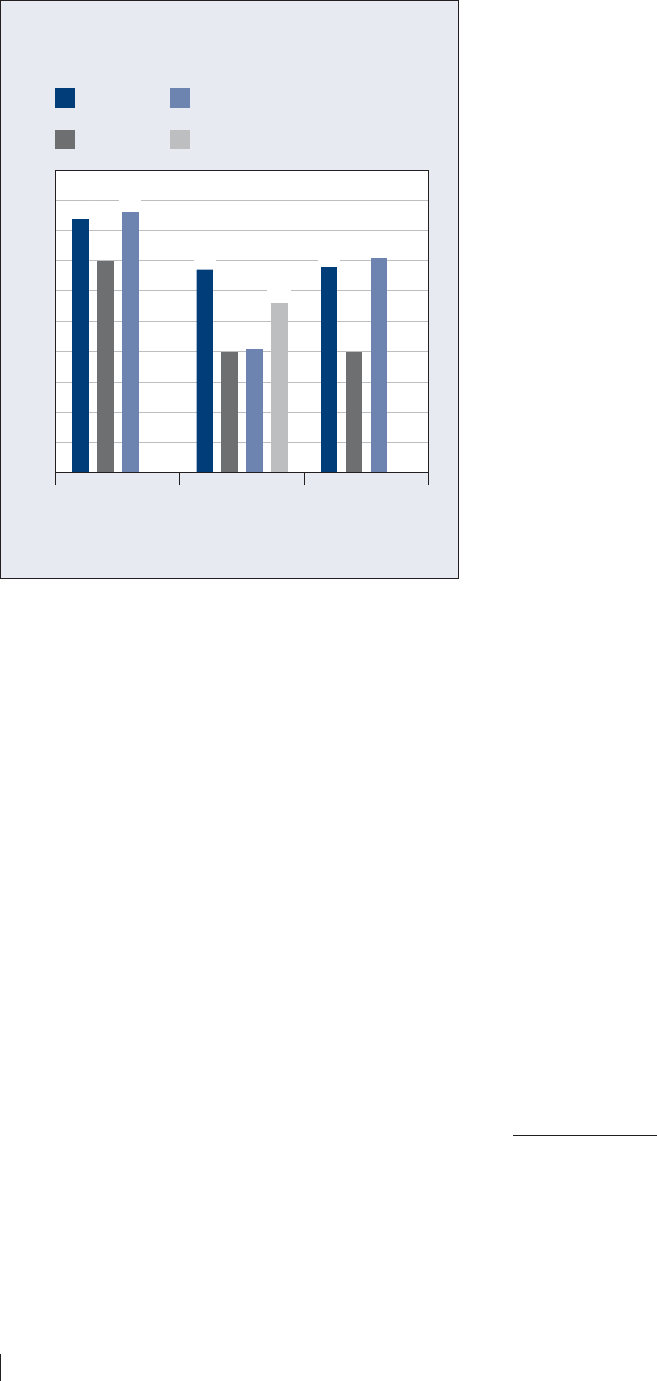

Another indicator of growing regional inte-

gration is the widespread support for bilateral free

trade agreements (FTAs) as well as surprisingly

strong support for an intraregional East Asian

free trade area including China, Japan, and South

Korea (see Figure 2).

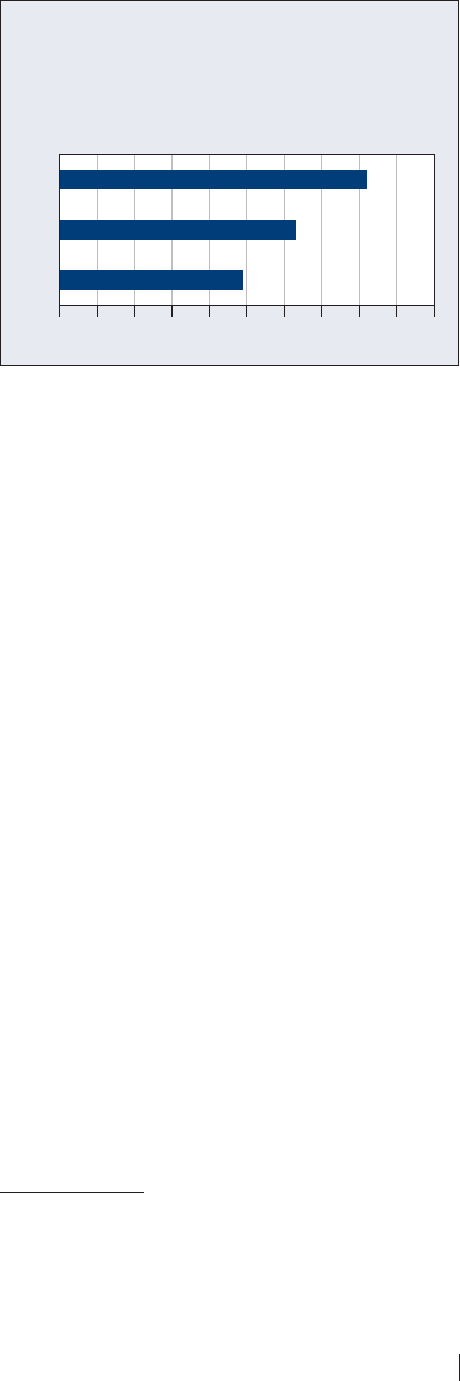

If such an FTA were formed, 56 percent

of Americans say the United States should

be included. However, only Chinese support

American inclusion (67%). Fifty-seven percent of

Japanese and South Koreans are against it.

A strong majority of Chinese (68%) favor the

integration of East Asian countries into a regional

community similar to the European Union (EU),

calling into question the idea that Chinese are

state-centric realists. South Koreans are even more

in favor (71%), while Japanese are more skeptical,

with only 40 percent in favor.

Regional Security

Greater interdependence between East Asian

countries, facilitated by rapidly growing trade in

recent years, has led some experts of the region to

hypothesize that the historical tensions between

countries will give way to greater cooperation and

make military conflict unthinkable. Current mili-

tary patterns, however, suggest that fears of one

another persist. Survey data confirm that even

though cooperation has grown and the publics

are in favor of even stronger economic ties, Asians

fear the military power of their neighbors and the

United States in the region. The data also show that

while there is unease about the American pres-

ence, it is overwhelmed by concerns about neigh-

boring countries. Although East Asia is presently

peaceful, important changes are under way.

3

Almost all militaries across the Asian region

are modernizing their forces.

4

In 2007 Asia

accounted for five of the world’s ten largest stand-

ing armies (China, India, North Korea, South

Korea, Vietnam) and the world’s four largest sur-

face navies (if the United States and Russian navies

are included, along with China and Japan). In

terms of total defense expenditures, Asia ranked

equal to European NATO nations in 2005 ($256

billion for Asia versus $259 billion for European

NATO countries), but totaled only half that of the

United States ($495 billion). China and Japan had

the second and fourth largest defense budgets in

the world in 2005 (the United States ranked first

and Russia third). For most East Asian nations,

military modernization programs involve import-

ing sophisticated weaponry from abroad. Six of the

world’s top ten arms importers are in Asia (China,

India, Japan, Pakistan, South Korea, Taiwan),

although in aggregate the Middle East still imports

more than Asia. China’s military modernization

program has been particularly intensive over the

3. See Ashley Tellis, Mercy Kuo, and Andrew Marble, eds.,

Strategic Asia 2008-2009: Challenges and Choices (Seattle:

National Bureau of Asian Rsearch, 2008); David Shambaugh

and Michael Yahuda, eds., International Relations in Asia

(Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008).

4. See Ashley Tellis and Michael Wills, eds., Strategic Asia

2005-2006: Military Modernization in an Era of Uncertainty

(Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2005).

Figure 2 – Free Trade Areas

Percentage in each country who favor the following.

84

70

86

67

40

41

56

68

40

71

Favor free trade

area including

China, Japan, and

South Korea

If such an area is

created, favor

including the U.S.

Favor East Asian

countries

integrating into

EU-like community

0

10

NA NA

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

China

Japan

South Korea

U.S.

5ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

past two decades, and this has raised concerns in

the United States and throughout the region. To

offset China’s growing capabilities and uncertain

intentions, the United States has been strengthen-

ing its five bilateral alliances in the region (with

Australia, Japan, Republic of Korea, Philippines,

and Thailand) as well as building defense ties with

nonallied states such as Singapore, Indonesia,

Mongolia, Vietnam, and India.

The regional insecurity suggested in this mili-

tary buildup is further reflected in Asian responses

to questions about how greater trade and more

cultural ties in East Asia have affected the possi-

bility of conflict in the region. Most answer that

the potential for conflict has increased. Nearly 60

percent of Chinese respondents believe that the

potential for conflict has either “very much” (29%)

or “somewhat” (29%) increased. Japanese opinion

is split. Only in South Korea does a majority (60%)

say that the possibility of conflict has decreased.

It is possible that South Koreans see much more

opportunity for growth in economic relationships

with the much larger economies of China and

Japan, whereas citizens from these larger Asian

countries are more wary of the potential for con-

flict over natural resources necessary for growth.

Respondents were also asked to rate the like-

lihood of future military conflict in East Asia

in the next ten years on a 0 to 10 scale in which

0 means no possibility for conflict and 10 means

that conflict is extremely likely. The average score

falls right around the middle of the scale—within

4.5 and 5.9 for all four countries where the ques-

tion was asked (China, Japan, United States, and

South Korea).

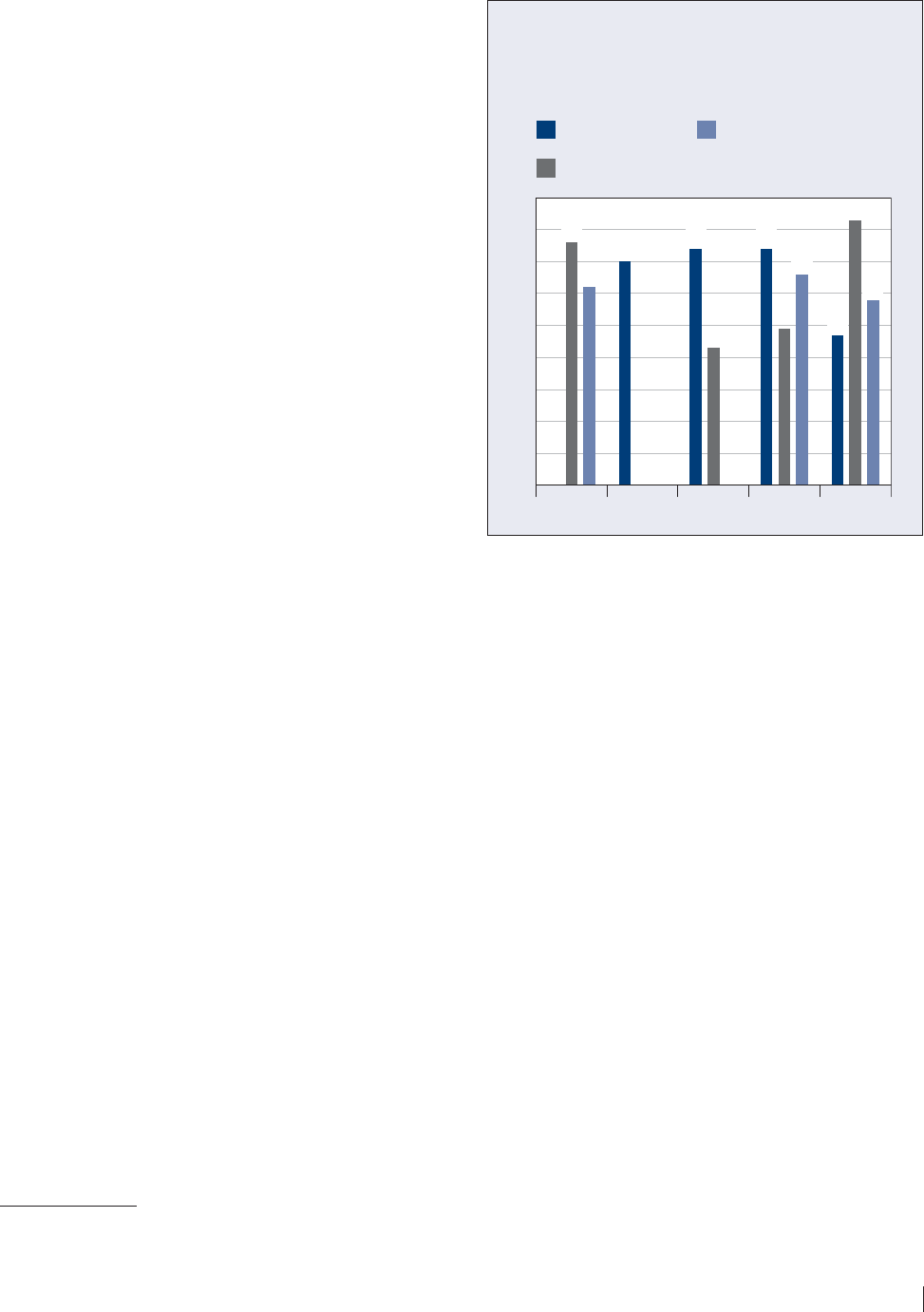

Still, majorities or pluralities in every country

are at least “somewhat worried” that China could

become a military threat to their country in the

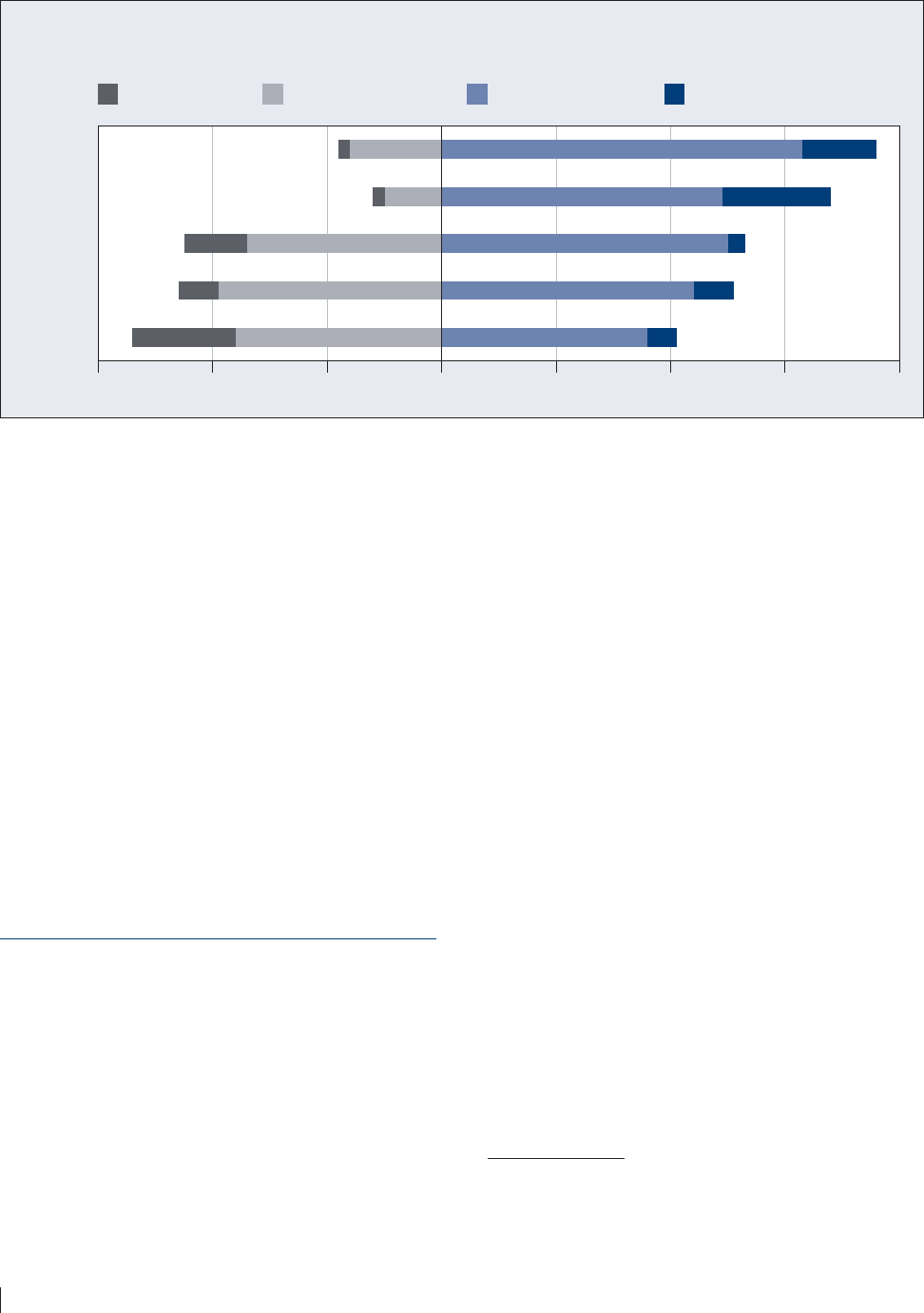

future (see Figure 3).

5

Despite Japan’s “peace con-

stitution,” majorities in China (62%), South Korea

(66%), and Indonesia (58%) are worried that Japan

may pose a future military threat to their respec-

tive countries. The Chinese are even more wor-

ried about a military threat from the United States

(76%) than Americans are worried about a Chinese

5. This question was not asked in Vietnam.

military threat (70%). While most Japanese and

South Koreans are not worried about a threat

from the United States, a substantial number are

at least somewhat worried (43% of Japanese and

49% of South Koreans). The greatest concern

about the United States is in Indonesia, a largely

Muslim country, where 83 percent of the popula-

tion is at least somewhat worried about a future

military threat. This view likely reflects concern

over U.S. military involvement in the Middle East

in recent years.

However worried some Japanese and Koreans

may be of a possible U.S. military threat to their

countries, majorities in South Korea (72%) and

Japan (68%) believe that the U.S. military pres-

ence in the region increases stability. Chinese are

more wary of American military forces in Asia

than the Japanese and South Koreans, with a slight

majority of Chinese (52%) believing that the U.S.

military presence in Asia decreases stability. Yet in

all five Asian countries, majorities believe that if

the United States removed its armed forces from

the region, it could spark a competitive military

buildup between China and Japan (see Figure 4).

Eighty-nine percent in South Korea, 79 percent in

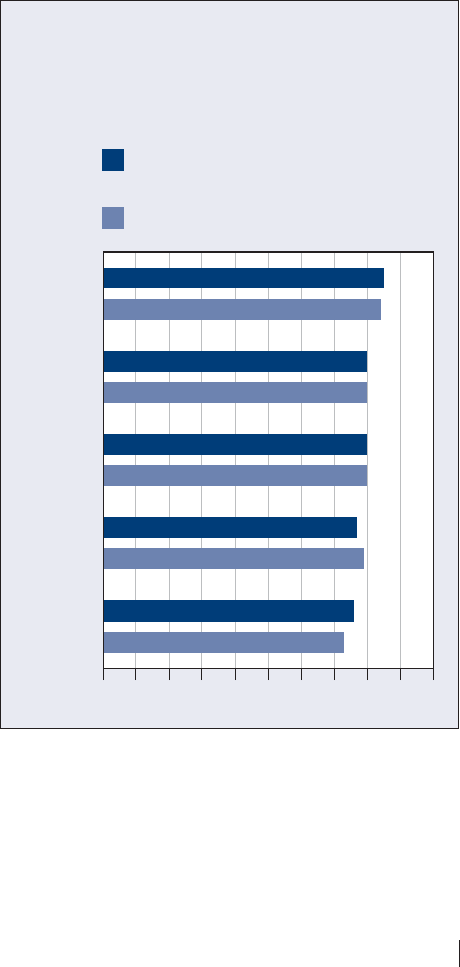

Figure 3 – Future Threats

Percentage in each country who are either

somewhat or very worried that China/U.S./Japan

could become a military threat in the future.

76

NA NA NA NA

62

70

74

43

74

49

66

47

83

58

China U.S. Japan South Korea Indonesia

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

China as threat

U.S. as threat

Japan as threat

6 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Japan, 75 percent in the United States, 61 percent

in China, and 57 percent in Indonesia say such a

scenario is at least “somewhat likely.”

A large U.S. presence in Asia is seen as a coun-

terbalance to the growing influence and power of

China in the region. Asked if they favor or oppose

their country supporting the United States in an

effort to balance China’s rise as a great political

and military power, 69 percent in Japan and 68

percent in South Korea are in favor. A slight major-

ity of Americans (51%) are in favor of a U.S. attempt

to contain China’s political and military power.

China has not softened the effect of its grow-

ing military power through effective diplomacy.

Throughout the region China is viewed as some-

what ineffective in dealing with regional prob-

lems. This is surprising given Beijing’s central role

in the Six Party Talks. When it comes to working to

resolve the North Korea nuclear issue, majorities

in Japan (59%) and South Korea (56%), along with

half of those surveyed in the United States (50%),

believe that China has been somewhat or very inef-

fective. By contrast, Chinese have a very positive

attitude on the effectiveness of other members of

the Six-Party Talks. They have an especially posi-

tive view of North Korea, with 69 percent saying

the country has been somewhat or very effective

in resolving the North Korea nuclear issue. The

United States is the only country about which

majorities or pluralities in all other countries say it

has been effective in resolving this nuclear weap-

ons problem.

On another regional security dilemma—per-

sistent tensions between China and Taiwan—fewer

respondents in each country agree that China and

the United States have been effective in dealing

with this issue. However, 64 percent of Chinese

agree that Taiwan has been “somewhat” or “very

effective” in helping to manage tensions. This per-

centage is only second to Chinese approval of their

own country’s handling of the issue.

Other territorial disputes in the region caus-

ing tensions between neighbors include (1) the

dispute between Korea and Japan over the island

known as “Dokdo” in Korean and as “Takashima”

in Japanese and (2) the dispute between China

and Japan over the islands “Diaoyu” or “Senkaku”

in their respective languages. Judging by pub-

lic attitudes, these islands are still very conten-

tious. On the Korea–Japan dispute, 78 percent

of South Koreans and 69 percent of Japanese say

their country should not be willing to compro-

mise on the issue. With regard to the China–Japan

dispute, 80 percent of Chinese and 72 percent of

Japanese say their country should not be willing

to compromise.

Overall, signs of hostility and suspicion still

exist among East Asian neighbors despite the

increased pace of regional economic integration.

The United States is perceived as an important

actor in the region, balancing the power of a rising

China and contributing to conflict resolution and

peaceful relations between neighbors.

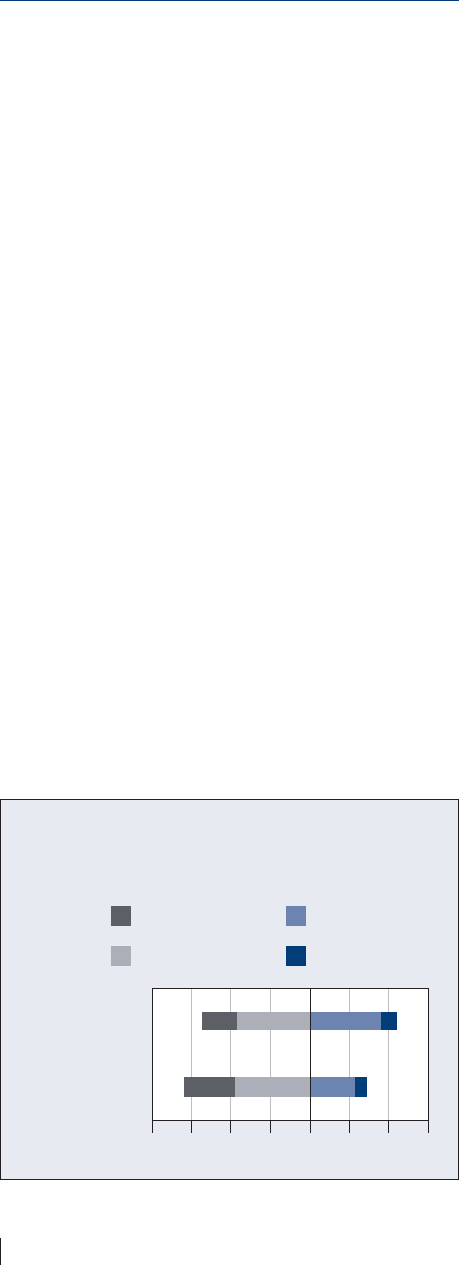

Figure 4 – China–Japan Arms Race

Percentage in each country who think it is somewhat

or very likely that China and Japan would build up their

militaries to compete with each other if the U.S.

removed its armed forces from East Asia.

75

61

79

89

57

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

U.S.

0102030405060708090 100

7ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

As interdependencies have grown, Asians (and

analysts of Asia) have increasingly begun to focus

on a new level of interaction—soft power— to bet-

ter understand regional dynamics and how we

might mitigate tensions between states. Harvard

University Professor Joseph Nye coined the term in

his famous book Soft Power: The Means to Success

in World Politics.

6

In his now classic study, Nye

equates soft power with attraction and asserts: “In

international politics, the resources that produce

soft power arise in large part from the values an

organization or country expresses in its culture, in

the examples it sets by its internal practices and

policies, and in the way it handles its relations with

others.”

7

Subsequent to the publication of Nye’s

book, many studies of American and European

soft power and public diplomacy ensued. More

recently, journalists, scholars, and government

analysts have begun focusing on China’s alleged

soft power.

8

6. Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in

World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004).

7. Ibid, 8.

8. Joshua Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft

Power is Transforming the World (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2008); Bates Gill and Yanzhong Huang, “Sources and

Limits of Chinese Soft Power,” Survival 48, no. 2 (Summer

2006): 17-36; Ingrid d’Hooghe, “Into High Gear: China’s Public

Diplomacy,” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 3 (2008): 37-61;

Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), China’s

Soft Power in Developing Regions (Washington, DC: CSIS Press,

March 2009); Congressional Research Service (CRS), China’s

Foreign Policy and “Soft Power” in South America, Asia, and

Africa (Washington, DC: United States Senate Committee

on Foreign Relations and U.S. Government Printing Office,

April 2008).

This study is the first public opinion survey

to evaluate soft power in Asia regionally. It ques-

tions how these nations view each other’s popular

culture, commercial prowess and brands, intel-

lectual influence and appeal, universities, diplo-

matic reputations and political systems. While the

People’s Republic of China has gained increasing

attention for its Asian diplomacy and regional soft

power, the other nations, aside from the United

States, have not been as closely examined, and

China’s alleged soft power has not been carefully

scrutinized using empirical survey data. This

study fills this gap and provides unique insights

into soft power in Asia.

Overall Soft Power Findings

To assist in the analysis of the report’s findings, the

results of many questions were combined to pro-

duce indices for each of five general areas of soft

power: economic, cultural, human capital, politi-

cal, and diplomatic. These five indices were then

averaged to produce an overall “Soft Power Index”

(see Figure 5). Changes in opinion were tracked on

a few key questions that were asked both in this

survey and in The Chicago Council’s 2006 Global

Views survey.

9

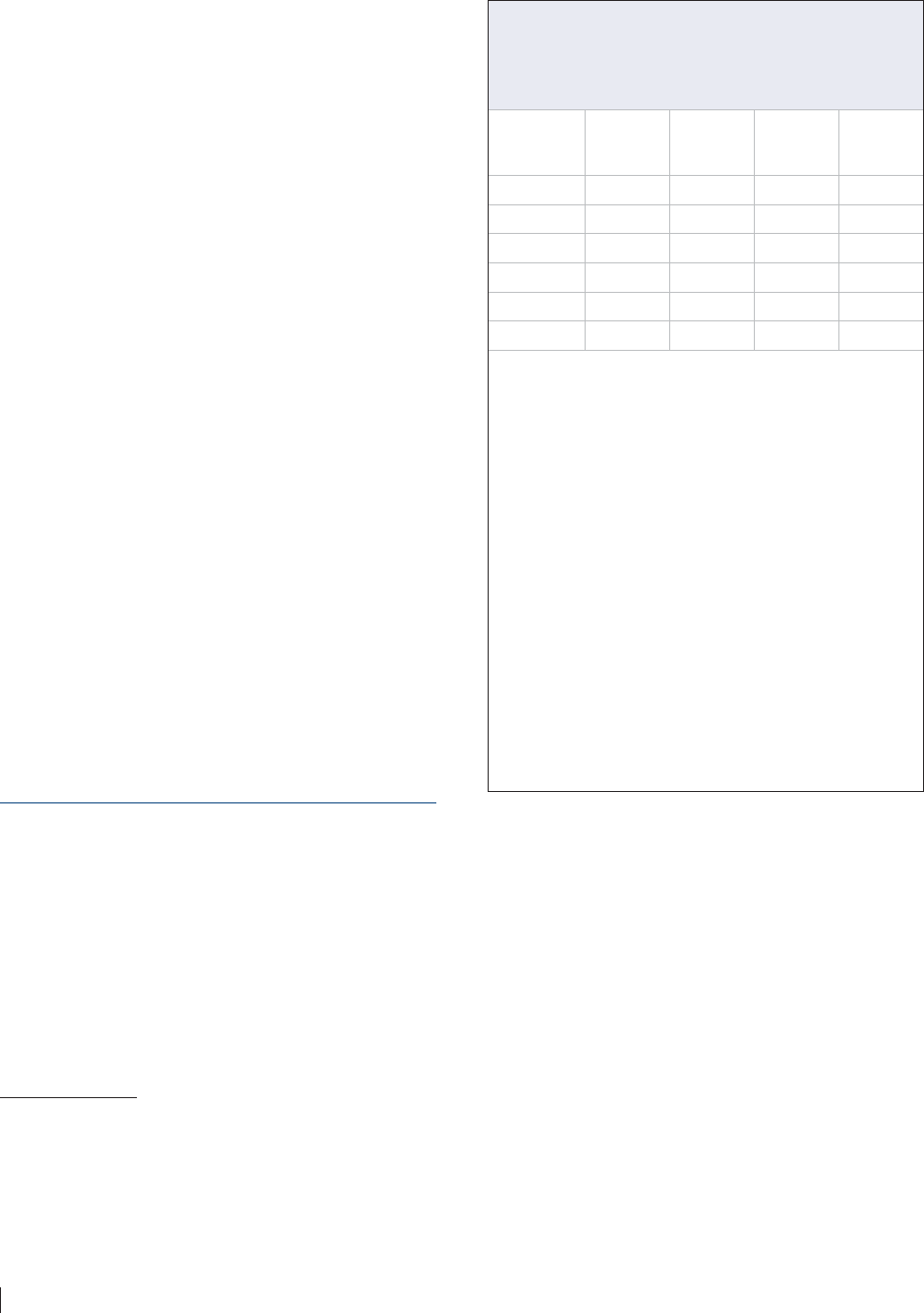

According to the overall Soft Power Index—

and contrary to conventional wisdom—the United

9. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Global Views 2006

(Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 2006).

Section II: Soft Power

8 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

States continues to possess significant soft power

in Asia. There is high recognition of U.S. economic,

cultural, and human capital soft power in all sur-

vey countries as well as great respect for its politi-

cal and diplomatic standing. American influence

in Asia has clearly not diminished recently and

remains very strong, especially among citizens of

the major powers. This gives the Obama admin-

istration a strong base to build upon. The United

States ranks highest on the index among Chinese,

Japanese, South Koreans, and Indonesians, and

second to Japan among Vietnamese, though not by

much. South Korea comes out consistently ahead

of China among Americans and Japanese. Con-

verse ly, Japan ranks last among Chinese respon-

dents. Although animosities are not as high as

expected, Chinese and Japanese generally rate the

other country lowest on most forms of soft power,

while general admiration is apparent between

Chinese and South Koreans. In contrast to the

great powers, Indonesian and Vietnamese citizens

believe Japan has slightly greater soft power than

the United States and that China ranks ahead of

South Korea. Thus, there appears to be a division

between the great powers and Indonesia/Vietnam

in terms of perceptions of soft power in Asia.

The following sections summarize the findings

for each of the five specific soft power indices.

Economic Soft Power

Every country has high respect for U.S. economic

soft power (see Appendix A). The United States

comes out on top among Japanese, Chinese, and

South Koreans, and second among Indonesians

and Vietnamese. Citizens in China,

10

Japan, and

South Korea believe the economic relationship

with the United States is their most important,

that the United States has the greatest economic

influence in Asia,

11

the U.S. economy is the most

10. Chinese give the economic relationship with the United

States and the European Union the same average score.

11. This ranking applies only to those given by each natio-

nal public to the other countries. Chinese believe the econo-

mic influence of their country is greater in Asia than that of the

United States. Japan places the United States a close second to

China in terms of economic influence.

internationally competitive, and the U.S. econ-

omy provides the best opportunities for its work-

force. Japan is a close second to the United States

in terms of perceived economic soft power and

is ranked even higher than the United States by

Indonesians and Vietnamese. China and South

Korea are almost always at the bottom of this

index, although China is generally slightly ahead

of South Korea. China tends to rank ahead of South

Korea in terms of perceived economic importance

to other countries and on the international com-

petitiveness and economic influence of China’s

economy in Asia. South Korea understandably

receives lower ratings on these questions com-

pared with the economic powerhouses of the

United States, China, and Japan. China suffers

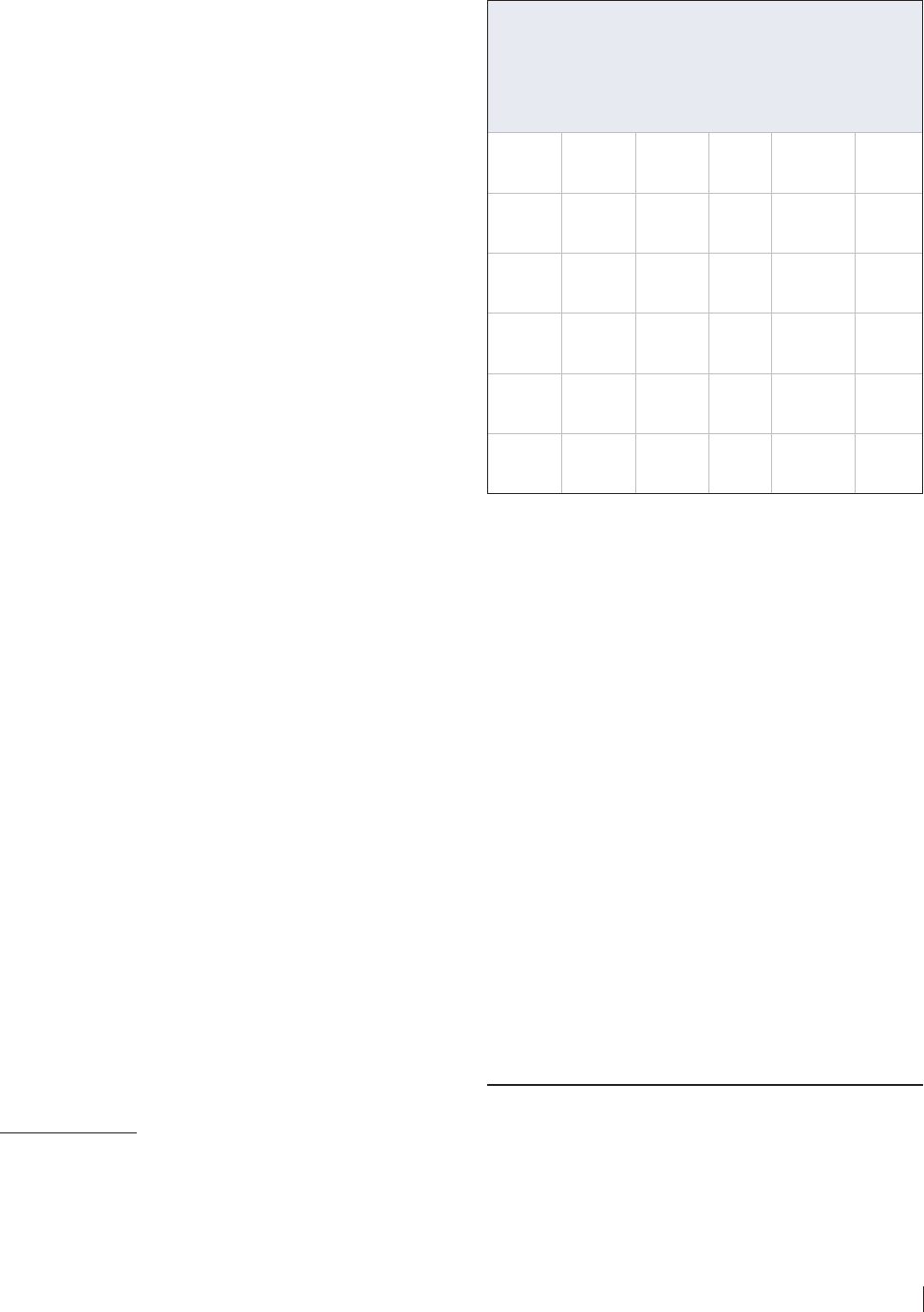

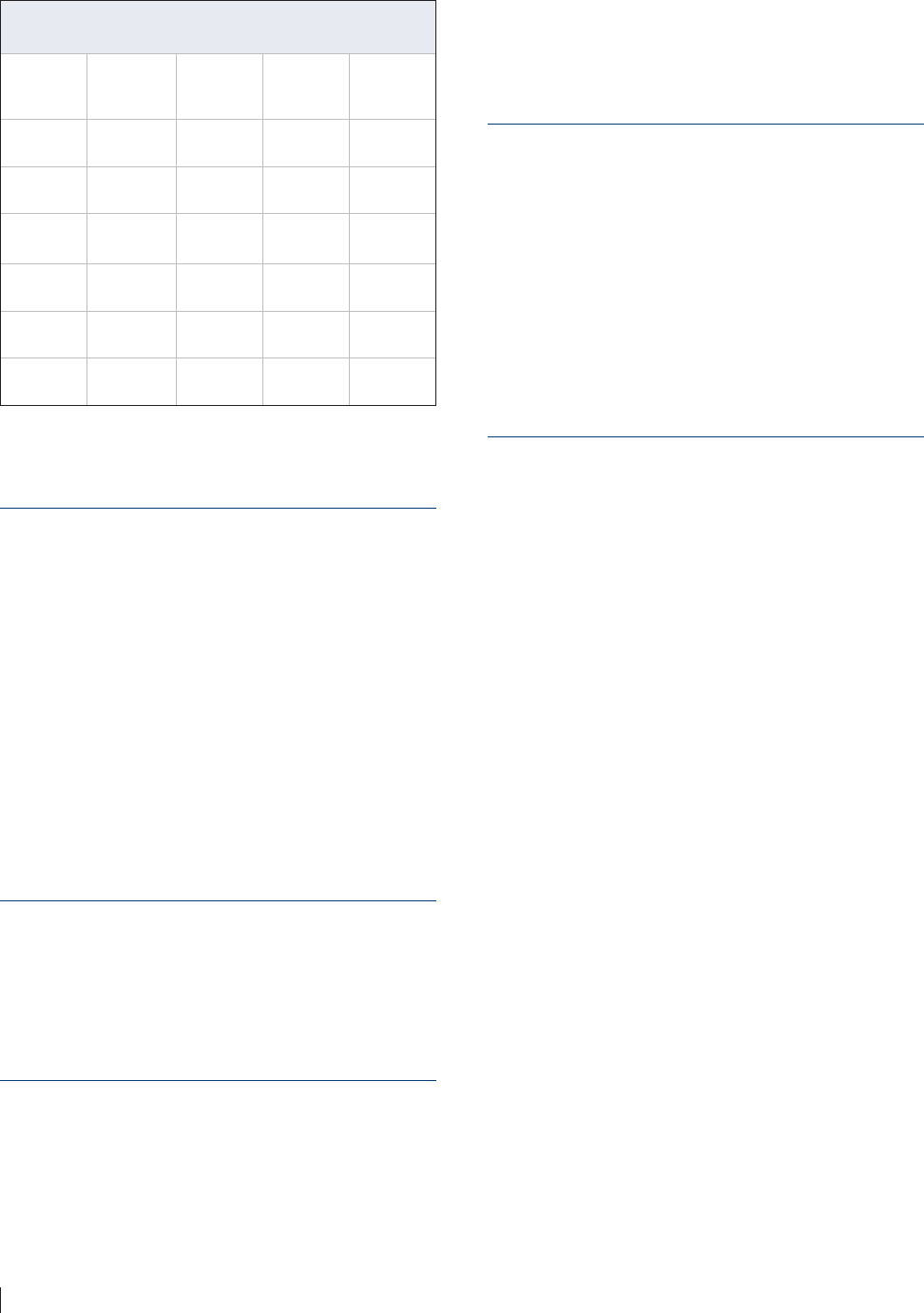

Figure 5 – The Soft Power Index

Average level of influence on a 0 to 1 scale

when soft power questions are combined,

followed by rank (see Appendix A for questions included).

Survey

Countries

U.S. soft

power

China soft

power

Japan soft

power

South

Korea soft

power

United States

— .47 (3) .67 (1) .49 (2)

China

.71 (1) — .62 (3) .65 (2)

Japan

.69 (1) .51 (3) — .56 (2)

South Korea

.72 (1) .55 (3) .65 (2) —

Indonesia

.72 (2) .70 (3) .72 (1) .63 (4)

Vietnam

.76 (2) .74 (3) .79 (1) .73 (4)

How the Soft Power Index Is Calculated

The questions in this survey were designed to measure Asian

attitudes regarding soft power. Various indices were created

as summary measures that represent the average rating for

each country for different aspects of soft power and provide

one basic rating of the overarching concepts. Each index was

created by standardizing the scales for several questions on a

particular aspect of soft power (i.e., cultural soft power), add-

ing together the scores for those questions, and then averag-

ing to arrive at a combined rating for “cultural soft power.”

Overall soft power is broken down into five separate indices

that each measures a different form of soft power—economic,

cultural, human capital, political, and diplomatic. Please refer

to Appendix A for a detailed listing of the questions includ-

ed in each index. The overall Soft Power Index was created

by averaging the soft power index scores for each of the five

different forms of soft power. Each of the soft power indices

was considered equally important and therefore they were

weighted equally in the overall score no matter how many

questions were included for that particular index.

9ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

from perceptions of low product quality, a lack of

humanitarian assistance to other Asian countries,

and the perception that there are few economic

opportunities for its workforce.

Cultural Soft Power

There is a clear divide between citizens of the major

powers and citizens of Indonesia and Vietnam in

their perceptions of cultural soft power. The United

States ranks

first according to Japanese, Chinese,

and South Koreans, but is last according to both

Indonesians and Vietnamese, who consider China

the preeminent purveyor of cultural soft power

in Asia (see Appendix A). Chinese, Japanese, and

South Koreans believe the United States has a great

degree of cultural influence in Asia, find American

culture appealing, and believe that the spread of

U.S. popular culture is positive. Indonesians find

U.S. culture appealing in general and think that

it has a great deal of influence in Asia, yet nearly

all Indonesians feel that the spread of U.S. culture

is a “bad thing” and has a negative influence on

Indonesia. Despite the fact that most Indonesians

think U.S. culture is attractive, Indonesians who

believe U.S. influence in Asia has increased in the

past ten years are less likely to think the spread of

U.S. culture is good. In contrast, Indonesian and

Vietnamese citizens believe Chinese culture has

a large and mainly positive impact on their own

societies. China is not considered much of a cul-

tural soft power by citizens of the major powers,

even though there is a general perception that

China possesses a rich cultural heritage. Japan and

South Korea generally rank in the middle on the

Soft Power Index. Although ratings of cultural soft

power differ somewhat on individual questions,

overall, Americans and Indonesians have greater

respect for Japanese cultural soft power, while

Vietnamese and Chinese have greater respect for

South Korean cultural soft power.

Human Capital Soft Power

Similar to economic soft power, citizens in nearly

every country surveyed (except Vietnam) believe

the United States possesses the greatest degree of

human capital soft power (see Appendix A). It is

notable that the United States rates so highly on this

scale and that there is a considerable gap between

the United States and the rest of the major powers.

There is general agreement that the United States

has a highly educated population, that it possesses

advanced science and technology, that it has qual-

ity universities, and that it is very important to

learn English. Japan, China, and South Korea are

once again second, third, and fourth, respectively,

on the index for nearly all of the surveyed coun-

tries. There is considerable respect for Japanese

science and technology among respondents in all

countries. China’s advantage over South Korea in

terms of human capital soft power lies in the higher

ratings it receives for science and technology and

the importance of learning Chinese over Korean.

Diplomatic Soft Power

The diplomatic Soft Power Index again shows a

major power/Southeast Asia divide. Japanese,

South Koreans, and Chinese believe the United

States possesses the greatest diplomatic soft power,

although Chinese rank South Korea slightly higher

than the United States (see Appendix A). Contrary

to conventional wisdom, within these countries

the United States has a good reputation for its use

of diplomacy, respect for sovereignty, and lead-

ership in international institutions. In contrast,

Indonesians and Vietnamese rate Japan slightly

higher and China relatively equal to the United

States on the overall diplomatic Soft Power Index.

Indonesians believe China and Japan use diplo-

macy more effectively to resolve key problems in

Asia and have a greater respect for sovereignty

than the United States. In addition, animosity

between Japan and China is evident on this index.

Citizens in neither country believe the other uses

diplomacy effectively (i.e., negotiations regard-

ing North Korea’s nuclear program and tensions

between China and Taiwan), and both Chinese

and Japanese believe the other fails to build trust

and cooperation among Asian countries. South

Korea is second and China third on the index in

10 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

the eyes of the United States and Japan, while

South Korea ranks last according to Indonesians

and Vietnamese in diplomatic soft power.

12

Political Soft Power

The United States and Japan are highly regarded

in the area of political soft power (see Appendix

A).

13

Citizens of China, Japan, and South Korea

believe the United States has the greatest respect

for human rights and possesses a political sys-

tem that serves the needs of its people. Japan has

ratings in the same range as the United States

from people in every country except China.

Interestingly, China rates quite poorly on this par-

ticular index. Citizens of the other major powers

agree that China possesses limited political soft

power, believing its political system does not serve

the needs of its people and that it has little respect

for human rights.

12. The Vietnamese index was based only on perceived

success of promoting policies in Asia. Vietnamese rank China

and South Korea equally, which places these countries third

after Japan and the United States on this index.

13. The questions on political soft power were not included

in the Vietnamese survey.

11ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Perceptions of the United States

For much of the post-World War II period,

America’s soft power has been felt strongly in Asia.

American universities have educated several gen-

erations of Asian professionals and elites, and its

popular culture—movies, music, sports, designer

goods—have penetrated deeply into Asian societ-

ies. The American democratic model has inspired

many Asian countries as they transitioned from

authoritarian to democratic political systems. The

American economy has been the main export mar-

ket for Asian producers for many years. American

missionaries have proselytized their religious

practices through Asian societies. Asian tourists

have flocked to Hawaii and the U.S. mainland.

Despite this sixty-plus-year legacy of American

soft power in Asia, the media has been filled with

reports in recent years of America’s declining

appeal throughout the region. This survey indi-

cates quite clearly that America’s soft power is still

robust and pervasive.

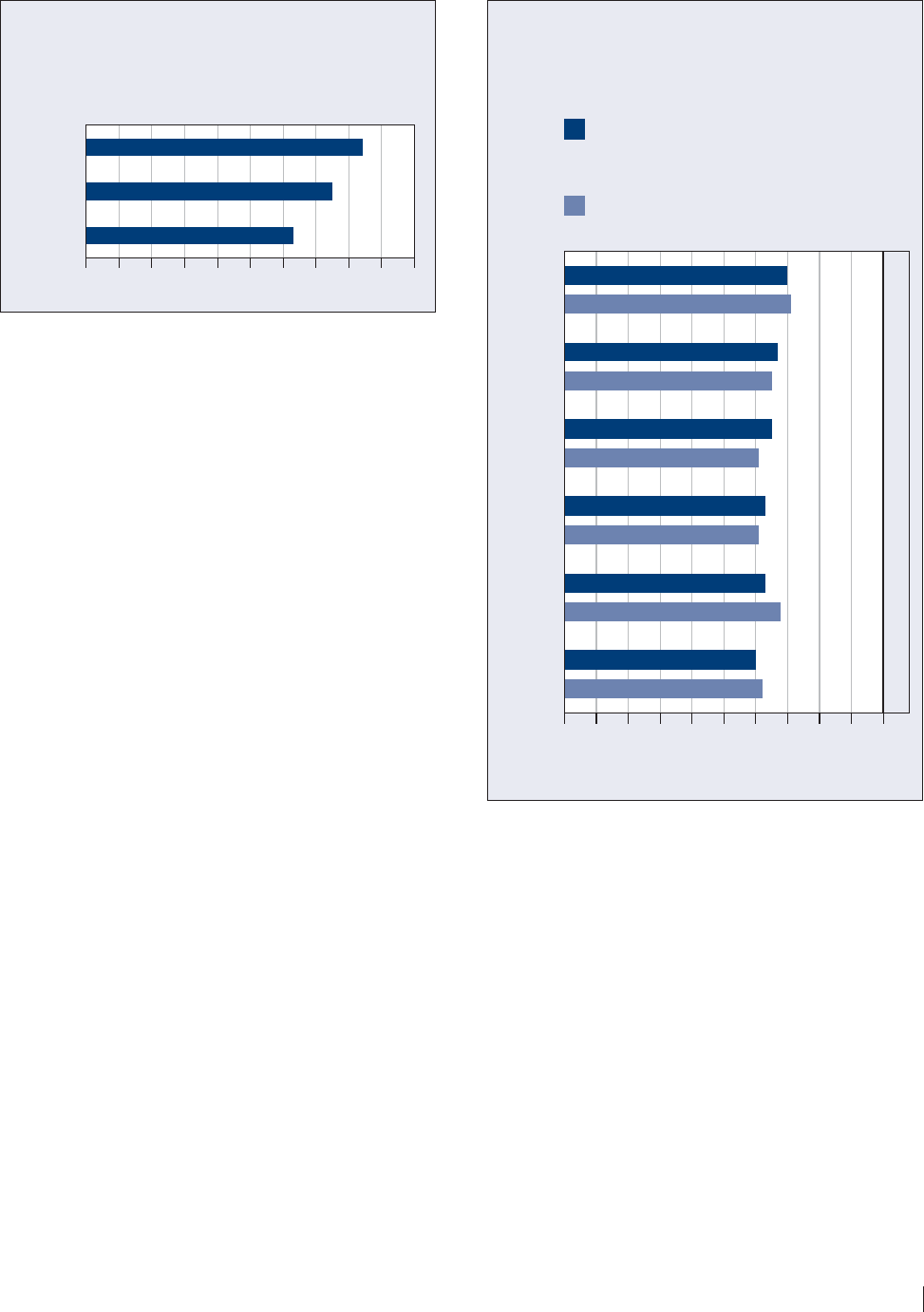

On a 0 to 10 scale of economic influence, the

United States ranks as either the first or second most

influential economic power in Asia in all the sur-

veyed countries. The United States receives a mean

level of 8.4 among South Koreans (see Figure 6),

ahead of both China and Japan. The United States

ties with Japan for first place among Vietnamese

(8.0) and Indonesians (7.9). However, the United

States ends up as the second most important eco-

nomic power after China among Chinese (7.3 to

8.0) and Japanese (8.0 to 8.2), with Chinese seeing

a larger gap between the two. American military

strength is perceived as significantly higher than

Section III: Perceptions of Individual Countries

Figure 6 – Economic Relations and

Inuence of the United States

Average rating by respondents in each country

(0 to 10 scale) on the following:

8.5

8.4

8.0

8.0

8.0

8.0

7.7

7.

9

7.6

7.3

China

Indonesia

Japan

Vietnam

South Korea

01 23 45 678 910

Importance of economic relations with

the U.S. such as trade and investment

to their country's economy.

Level of U.S. economic influence in Asia

12 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Chinese military strength among Japanese (9.0 vs.

7.9), South Koreans (8.7 vs. 7.7), and Indonesians

(8.6 vs. 6.7). However, Chinese and Americans see

the United States as just slightly behind China in

military power (8.0 to 8.1 among Chinese and 7.5

to 7.6 among Americans). Additionally, a majority

of Indonesians (58%) and pluralities of Japanese

(47%), Chinese (45%), and South Koreans (42%)

believe overall U.S. influence in Asia has increased

over the past ten years. Minorities ranging from 11

percent to 28 percent in the surveyed countries

believe U.S. influence has declined (see Figure 7).

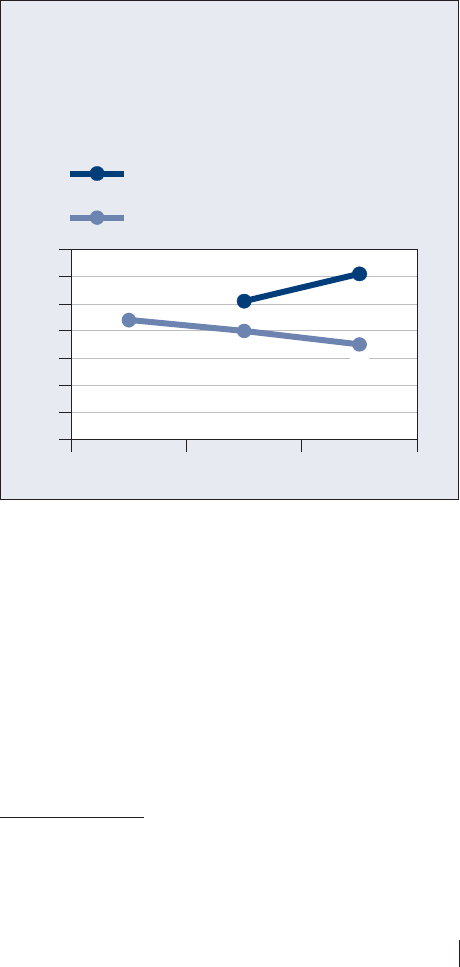

Feelings toward the United States are relatively

warm among the publics of the surveyed coun-

tries and have grown warmer among those coun-

tries that were also surveyed in the 2006 Chicago

Council “Global Views” study. On a scale of 0 to

100 where 50 is neutral, Chinese give the United

States a warm average of 61, ten points higher than

its average score in 2006 and the third highest rat-

ing overall after South Korea and Taiwan.

14

There

is a more modest warming trend in feelings toward

the United States among South Koreans (up three

points from 58 in 2006 to 61) and Indonesians (up

two points from 54 to 56), although this increase

is within the survey’s margin of error. The United

States receives its highest rating from Vietnamese

(68) followed by the Japanese (62). Unlike other

14. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Global Views

2006 (Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 2006).

international surveys that have shown a generally

unfavorable perception of U.S. global influence,

citizens of the surveyed Asian countries generally

perceive the United States as a positive influence

in their region. Majorities in Vietnam (76%), Japan

(69%), China (66%), and South Korea (54%) say

the United States is having a “somewhat” or “very

positive” influence in Asia. Only in Indonesia,

where perceptions of the U.S. role may be influ-

enced by U.S. foreign policy in other regions such

as the Middle East, do people feel more negative. A

plurality (48%) of Indonesians believe the United

States plays a “somewhat” or “very negative” role,

compared to 24 percent who say the opposite.

Broadly held beliefs within the surveyed

countries of the economic importance of the

United States to Asia likely contribute to positive

perceptions of the overall U.S. role in Asia. There

is wide recognition that U.S. ideas on the benefits

of free markets and open competition have been

influential in the region. Majorities in all surveyed

countries—94 percent in Japan, 93 percent in

South Korea, 76 percent in Indonesia, 71 percent

in China, and 56 percent in Vietnam—say these

ideas have been “somewhat’ or “very important”

in their countries’ economic development. There

is also a prevalent perception that the United

States has the most competitive economy. On a 0

to 10 scale evaluating economic competitiveness

of different economies, the United States both

scores the highest among all assessed countries

and is significantly ahead of both Japan and China.

The United States receives an average score of 8.9

among Vietnamese, compared to 8.6 among South

Koreans, 8.4 among Japanese, and 8.1 among both

Chinese and Indonesians.

On the same 0 to 10 scale, the United States is

considered the most important trade and invest-

ment partner (see Figure 6) for Japan (8.0) and

Vietnam (8.0). Chinese give both the United States

and the European Union the same score (7.6), sig-

nificantly ahead of Japan (6.7) and South Korea

(6.8). Similarly, support for signing free trade

agreements with the United States (see Figure 8)

is higher than that for any other potential bilateral

agreement asked of the surveyed Asian popula-

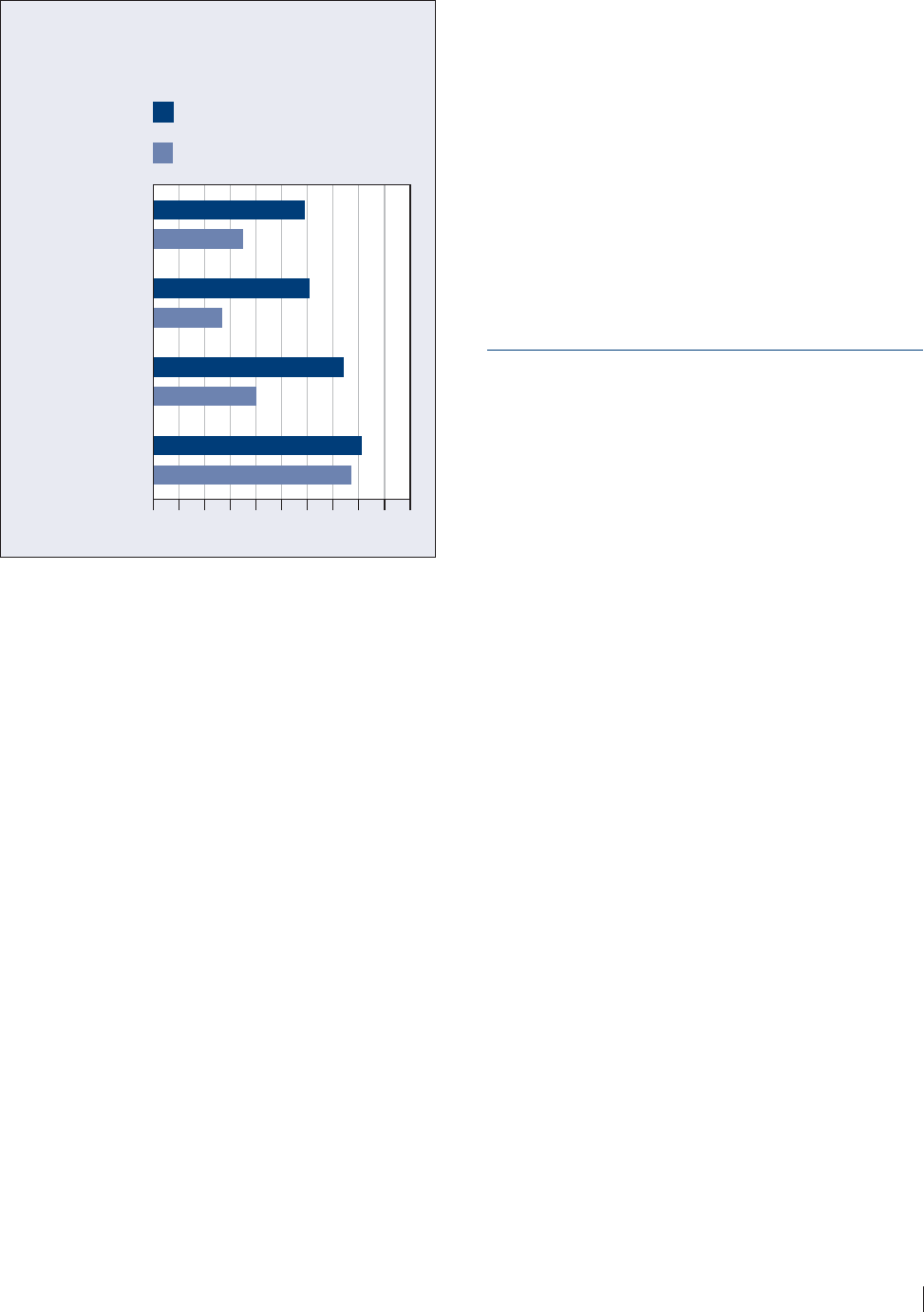

Figure 7 – U.S. Inuence in Asia

Percentage in each country who say U.S.

influence over the past ten years has decreased, increased,

or remained about the same.

265022

452428

473220

423324

581811

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

U.S.

60 40 20 020406080

Increased

Remained about

the same

Decreased

13ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

tions except for the Japanese—a slightly higher

percentage say their country should have a free

trade agreement with South Korea.

Asians also generally regard the United States

as a highly advanced technological power with

strong multinational corporations that are posi-

tively engaged in the region. On a 10-point scale

assessing the degree to which countries possess

advanced science and technology, the United

States scores the highest in every country: 9.1 in

Vietnam, 8.9 in South Korea, 8.8 in Indonesia and

China, and 8.4 in Japan. The United States also

receives the highest average scores of any coun-

try on the degree to which it has leading multi-

national companies. American companies are

generally viewed favorably, with majorities in

Vietnam (86%), Japan (80%), South Korea (75%),

China (73%), and Indonesia (54%) believing

U.S. companies make a positive contribution in

their countries.

Asians have mixed perceptions of the impact

of the U.S. military presence in the region. Strong

majorities of South Koreans (72%) and Japanese

(68%) believe the U.S. military presence increases

stability in East Asia, while 52 percent of Chinese

disagree. Indonesians are split (35 percent say it

increases stability and 38 percent say the oppo-

site). Indonesians and Chinese also have the

strongest concerns about the United States as a

potential military threat to their countries. South

Koreans are surprisingly mixed on this question,

with 49 percent worried and 50 percent not wor-

ried. However, there is agreement in all surveyed

countries, including the United States, that the

U.S. military presence keeps China and Japan

from entering into an arms race.

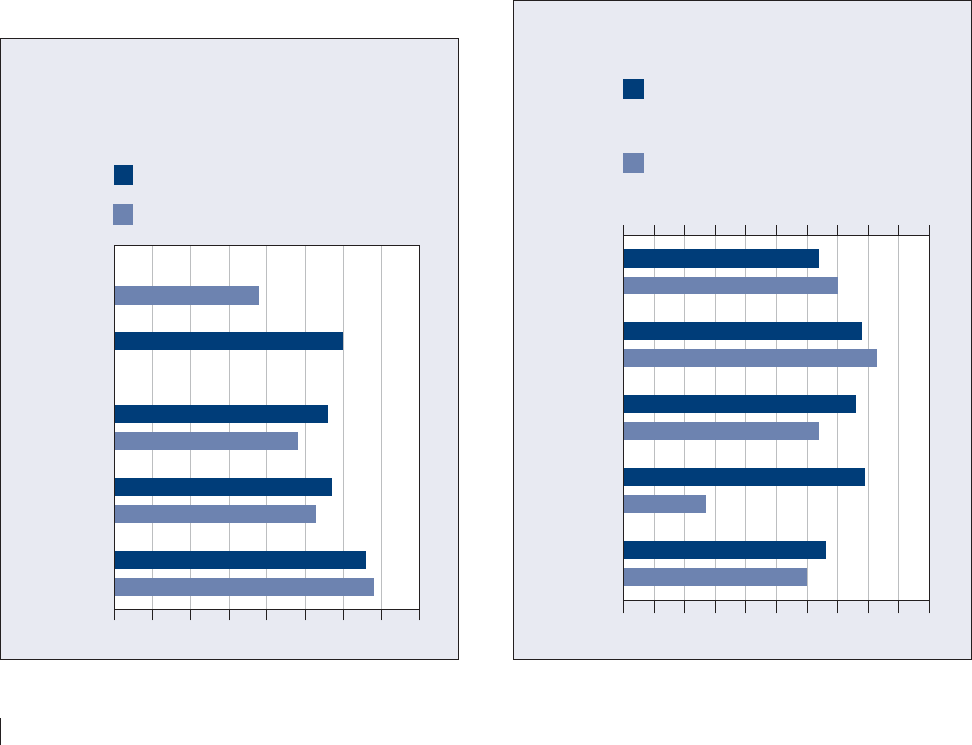

Asians generally consider U.S. public diplo-

macy in the region to be effective. On a 0 to 10 scale

evaluating how successful the United States and

China are in promoting their ideas about the best

world order, Japanese (6.0), South Koreans (6.3),

and Indonesians (7.0) all see the United States as

significantly more effective (see Figure 9) than

China (4.5, 4.9, and 6.6, respectively). Chinese dis-

agree, giving their own country a score of 7.7 com-

pared to 6.7 for the United States. Vietnamese see

China and the United States as equally effective

(6.3). A similar pattern emerges on a 10-point scale

assessing the effectiveness of the U.S., Chinese,

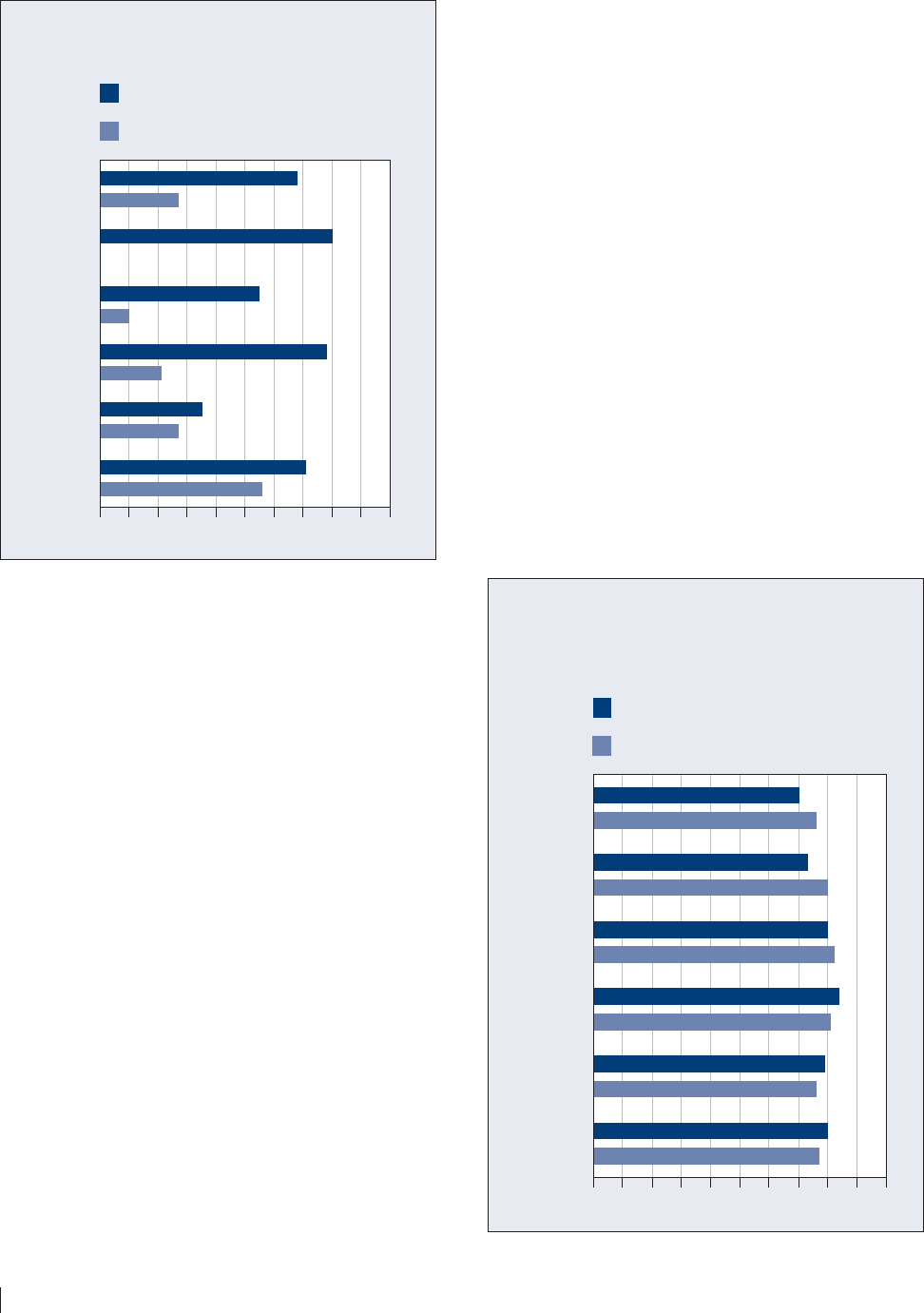

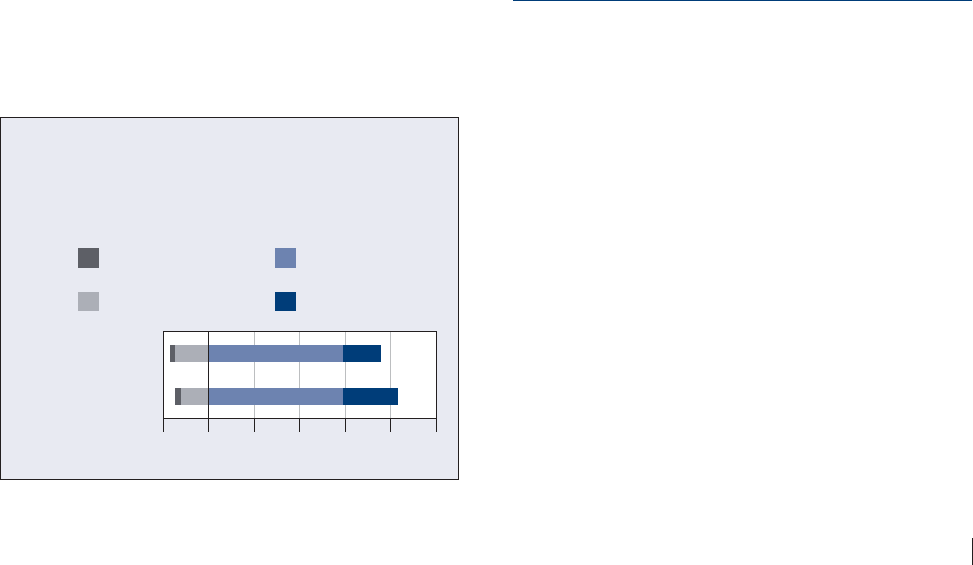

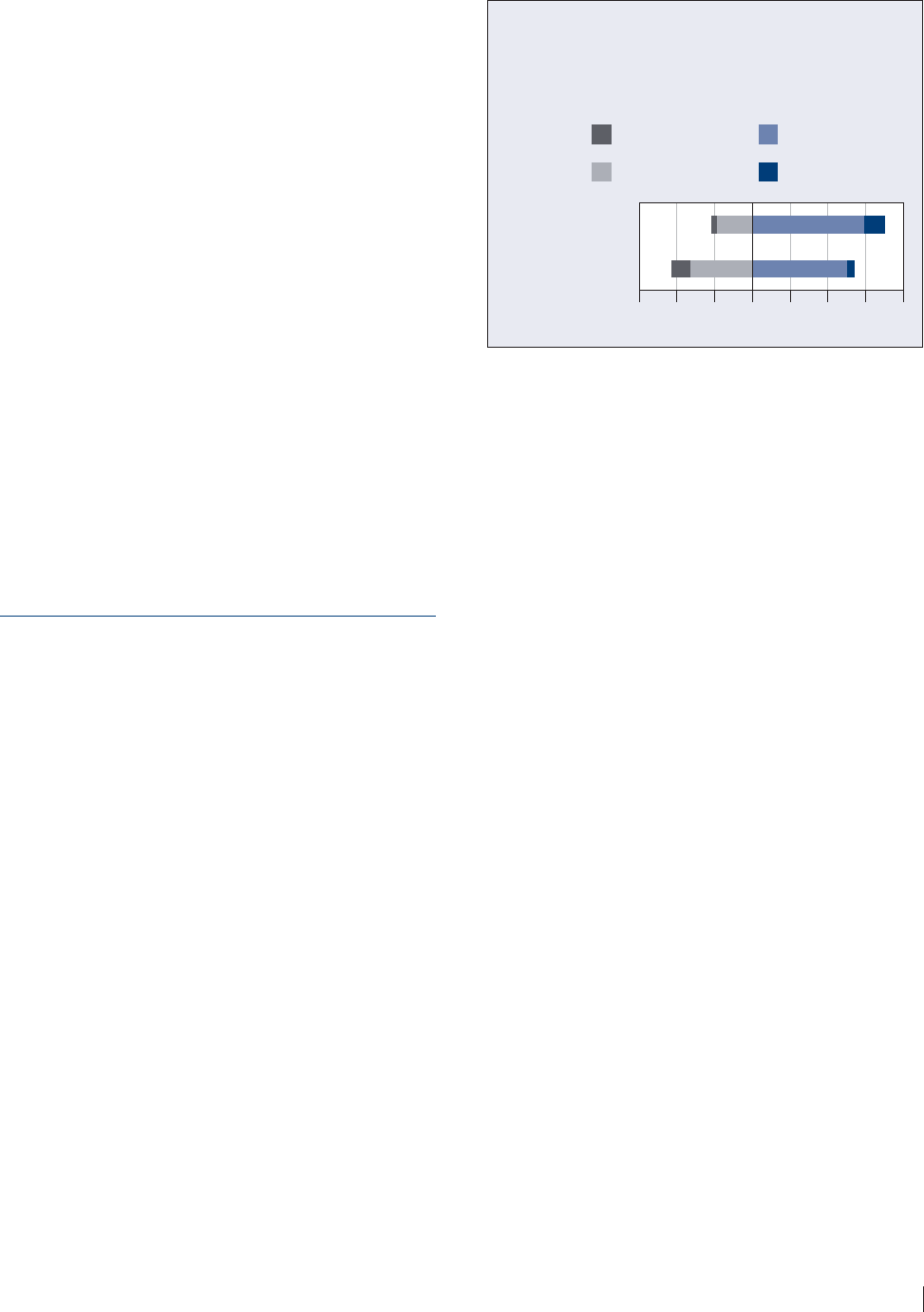

Figure 9 – Promoting Ideas/Policies in Asia

Average rating by respondents in each country

(0 to 10 scale) on the following:

7.0

7.1

6.7

6.5

6.5

6.1

6.3

6.1

6.3

6.8

6.0

6.2

Japan

Vietnam

South

Korea

U.S.

China

Indonesia

Rank

1

1

2

2

1

1

1

1

1*

2

1

1

01 2 34 56 7 8910

How effective the U.S. has been in

promoting its ideas about the best

world order

How effective the government of

the U.S. has been in promoting its

policies to the people of Asia

*The United States tied with China on this question among Vietnamese.

Figure 8 – Free Trade Agreements

with the United States

Percentage who think their country should have a free

trade agreement with the United States.

Japan

South Korea

China

0102030405060708090 100

84

75

63

14 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Japanese, and South Korean governments in pro-

moting their policies to people in Asia. The United

States gets the highest average score (see Figure

9) among Indonesians (7.1), Japanese (6.2), and

South Koreans (6.1), but is second to China in the

eyes of Chinese (6.5 compared to 7.8) and second

to Japan in the eyes of Vietnamese (6.8 compared

to 7.1).

Asians also generally see the United States

as the most effective of the four countries in its

leadership of international institutions like the

United Nations and the World Trade Organization.

American efforts to promote democracy and

human rights internationally are generally viewed

as having had a positive effect on Asia by majori-

ties of Japanese (60%), South Koreans (55%),

Indonesians (50%), and Chinese (50%). American

use of diplomacy to resolve problems in Asia is

also generally well regarded. On a 0 to 10 scale

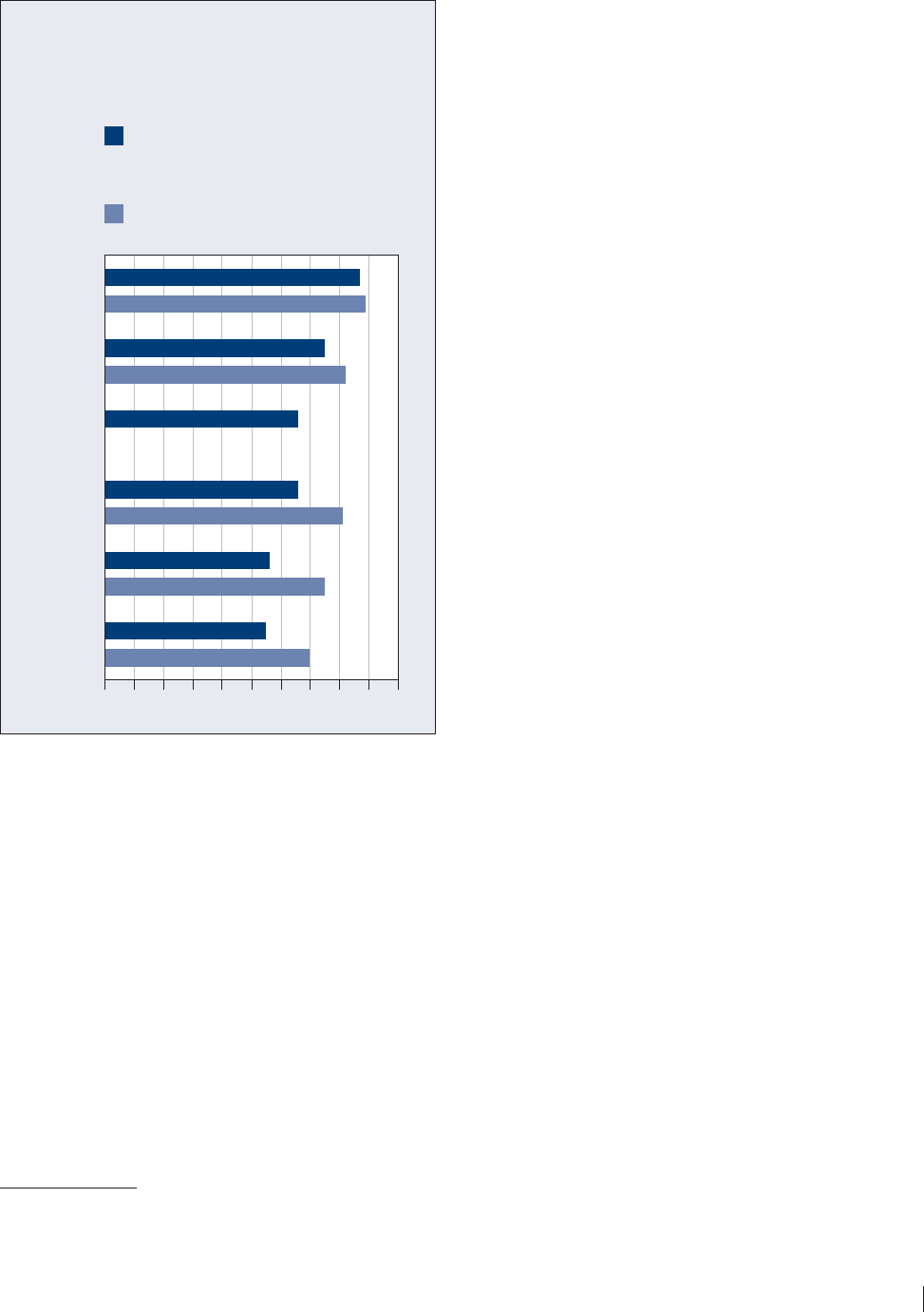

assessing this issue (see Figure 10), the United

States receives the highest average score of any

foreign country from Chinese (6.0, on par with

South Korea), South Koreans (5.7), and Japanese

(5.6). Among Indonesians, the United States

places third (6.6) behind Japan (7.1) and China

(6.8). Majorities of South Koreans (70%), Chinese

(67%), and Japanese (57%) also believe the United

States has been “very” or “somewhat effective” in

working to resolve the problem of North Korea’s

nuclear weapons program. A surprisingly strong

majority of Chinese (63%) believe the United

States has been effective (“very” and “somewhat”

combined) in managing tensions between main-

land China and Taiwan, although Chinese percep-

tions of U.S. respect for sovereignty is lower (5.1 on

a 0 to 10 scale).

U.S. cultural influence is both pervasive and

considered generally positive among surveyed

Asian countries. It is seen as the strongest foreign

popular culture influence among Indonesians

(7.9 on a 0 to 10 scale), Japanese (7.8), and South

Koreans (7.6). Among Chinese, it is second only to

South Korea in cultural influence (6.4 compared

to 6.5). Among Vietnamese, U.S. cultural influence

ranks last of the four assessed cultures (American,

Figure 10 – Use of Diplomacy

Average rating by respondents in each country on

how well the U.S./China uses diplomacy to resolve

key problems in Asia (0 to 10 scale).

3.8

6.0

5.6

4.8

5.7

5.3

6.6

6.8

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

U.S.

NA

NA

012345678

U.S. use of diplomacy

China’s use of diplomacy

Figure 11 – U.S. Cultural Inuence

6.4

7.8

7.6

7.9

6.6

70

83

64

27

60

Vietnam

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

0 12345678910

0102030405060708090 100

Level of influence U.S. culture has on

each country’s popular culture (mean

score on a 0 to 10 scale)

Percentage in each country who think the

influence of U.S. popular culture on their

country’s popular culture is mainly positive

15ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean). The United

States ranks first in terms of the appeal of its pop-

ular culture in every surveyed country except for

Vietnam, where it ranks fourth after China, Japan,

and South Korea. American movies, television pro-

grams, and music are the most frequently viewed

or listened to among all non-native entertainment

in every surveyed country with the exception of

Vietnam, where South Korean and Chinese enter-

tainment rank higher.

Strong majorities of Japanese (83%), Chinese

(70%), South Koreans (64%), and Vietnamese

(60%) believe U.S. cultural influence on their

popular culture is generally positive (see Figure

11). Indonesians strongly disagree (60% believe it

is negative). Similarly, the spread of U.S. cultural

influence in Asia is considered a positive develop-

ment by the publics of all surveyed Asian coun-

tries except Indonesia, where 75 percent see it as

negative. In contrast, 72 percent of Japanese, 69

percent of Chinese, 63 percent of Vietnamese, and

57 percent of South Koreans view the spread of

U.S. cultural influence favorably.

Overwhelming majorities (96% to 100%) in the

five Asian countries surveyed believe it is at least

somewhat important for children in their country

to learn English in order to succeed in the future.

Many Asians also look to the United States as an

educational destination for their children. The

United States is the first- or second-choice des-

tination for higher education for the children of

Asian parents, and there is a belief that the United

States has the highest quality universities.

Perceptions of China

Much has been made in recent years of China’s

growing influence and soft power globally, par-

ticularly in Asia.

15

Many media reports even

link China’s improved image in Asia as com-

ing at the expense of America’s, which is seen as

in decline.

16

15. See n. 8.

16. Jane Perlez, “The Charm from Beijing: China Strives

to Keep Its Backyard Tranquil,” New York Times, October 8,

2003; Jane Perlez, “Asian Leaders Find China a More Cordial

Neighbor: Beijing’s Soaring Economy Weakens U.S. Sway,” New

Yet the data from this survey indicate China’s

soft power in the region is, in fact, uneven. On

several indices it is quite limited. Beijing scores

consistently higher in Southeast Asia (Indonesia

and Vietnam) than in other respondent countries

(United States, Japan, and South Korea), where

respondents are much more circumscribed in

their perceptions of Chinese soft power (see Figure

12). Chinese hold a very high opinion of their own

country’s soft power—ranking China considerably

higher than it ranks in other respondent countries

across virtually all categories.

Overall, perceptions of China in the region

are mainly positive. Clear or strong majorities in

all respondent countries assess China’s overall

regional influence as either “very” or “somewhat

positive” (53% in the United States, 62% in Japan,

58% in South Korea and Indonesia, and 76% in

Vietnam). Majorities of respondents in all coun-

tries (except Indonesia) also believe that China

York Times, October 18, 2003; Jane Perlez, “As U.S. Influence

Wanes, A New Asian Community,” New York Times, November

4, 2004; Editorial, “China’s More Nuanced Diplomacy,” New

York Times, October 14, 2003; Philip Pan, “China’s Improving

Image Challenges U.S. in Asia,” Washington Post, November 15,

2003; Michael Vatikiotis and Murray Hiebert, “How China Is

Building an Empire,” Far Eastern Economic Review, November

20, 2003, 30–33.

Figure 12 – Ratings of China’s Soft Power:

The View Is Better from the South

Average level of influence on a 0 to 1 scale when

soft power questions are combined for five key areas

(see Appendix A for questions included).

Survey

Countries

Economic

Human

Capital

Cultural

Diplomatic

Political

United

States

0.52 0.55 0.56 0.40 0.34

Japan

0.57 0.58 0.57 0.44 0.41

South

Korea

0.57 0.64 0.54 0.51 0.48

Indonesia

0.73 0.74 0.62 0.69 0.71

Vietnam

0.70 0.80 0.77 0.67 —

16 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

will be the “leader of Asia” in the future. Only

in Vietnam is a majority of the public comfort-

able with this possible future development (see

Figure 13).

On a 0 to 100 scale of feelings toward China

where 50 is neutral, the country scores lower. The

mean score given by Americans is a chilly 35, while

the mean given by Japanese is 45. South Koreans

have neutral feelings at 50, down from 57 in the

2006 Chicago Council survey. Indonesians have

warmer feelings at 60, as do Vietnamese at 62.

Skepticism about China is also evident when

respondents are asked whether their country

shares similar values with China. With the notable

exception of Vietnam and to a lesser extent South

Korea, majorities in the United States, Japan, and

Indonesia all believe that their values converge

either “a little” or to “no extent” with China. With

respect to China’s political system, when asked

whether China’s political system serves the needs

of its people, with the exception of Indonesia, the

mean score is 5.1 or below on a 10-point scale.

Similarly, on a 10-point scale of respect for human

rights and the rule of law, with the exception of

Indonesians (6.8), China receives low average

ratings from Americans (2.7), Japanese (3.9), and

South Koreans (4.5).

Concerning economic dimensions of soft

power, China does fairly well. On the question of

how important economic relations with China are

to their country, responses in all countries aver-

age between 6.5 and 8.3 on a 0 to 10 scale. Further,

China’s economic influence in Asia is consid-

ered to be very high, scoring between 7.6 and 8.2

across all survey countries (see Figure 14). This is

an important finding, given China’s centrality in

the regional production chain and as a catalyst

for economic growth in East Asia. Nevertheless,

Chinese are judged to have somewhat average

entrepreneurial spirit, and the quality of Chinese

products receives mixed reviews.

Chinese diplomacy, unlike its economic influ-

ence, receives surprisingly low assessments. Asked

if China uses diplomacy to resolve key problems in

Asia or builds trust and cooperation among Asian

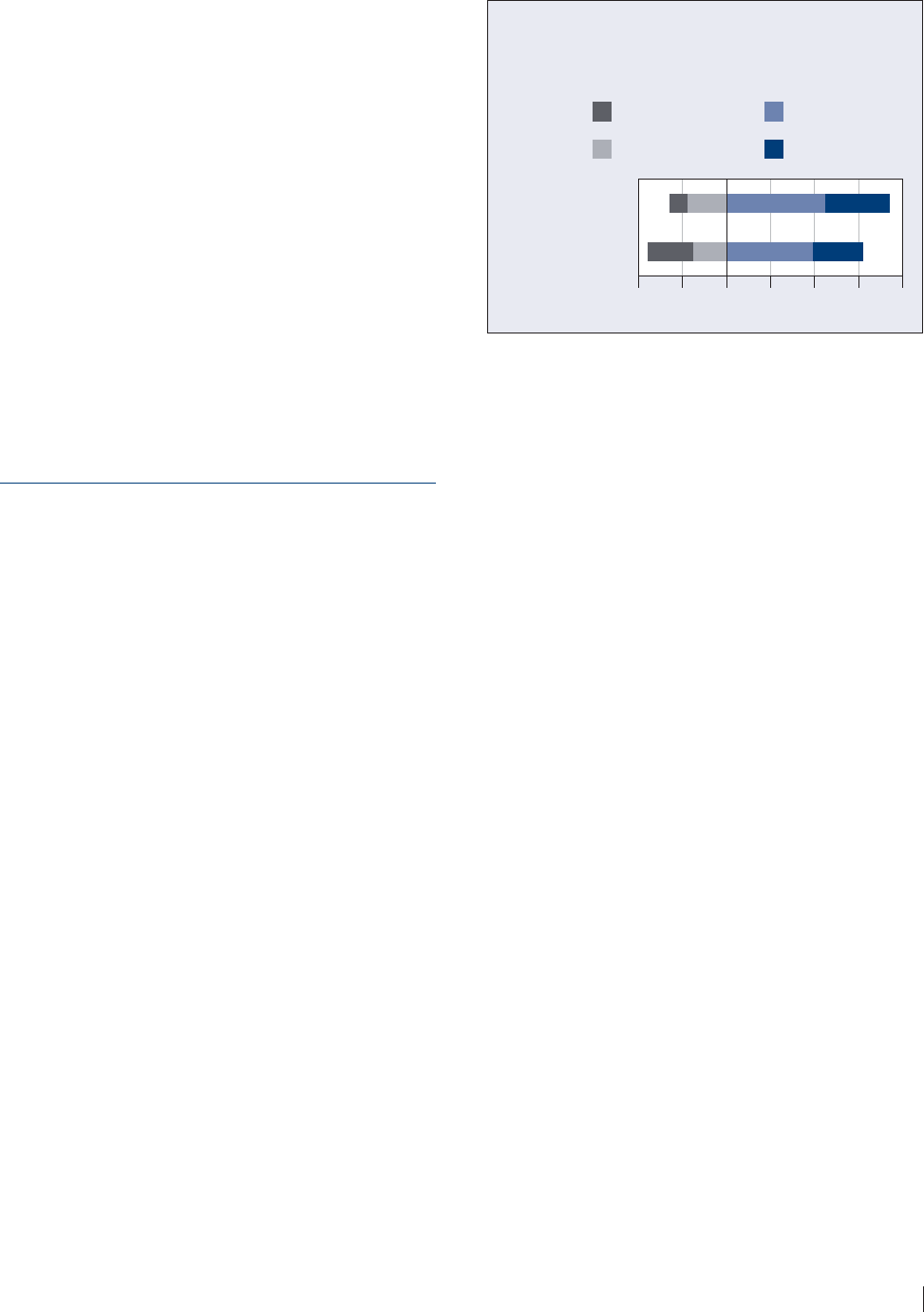

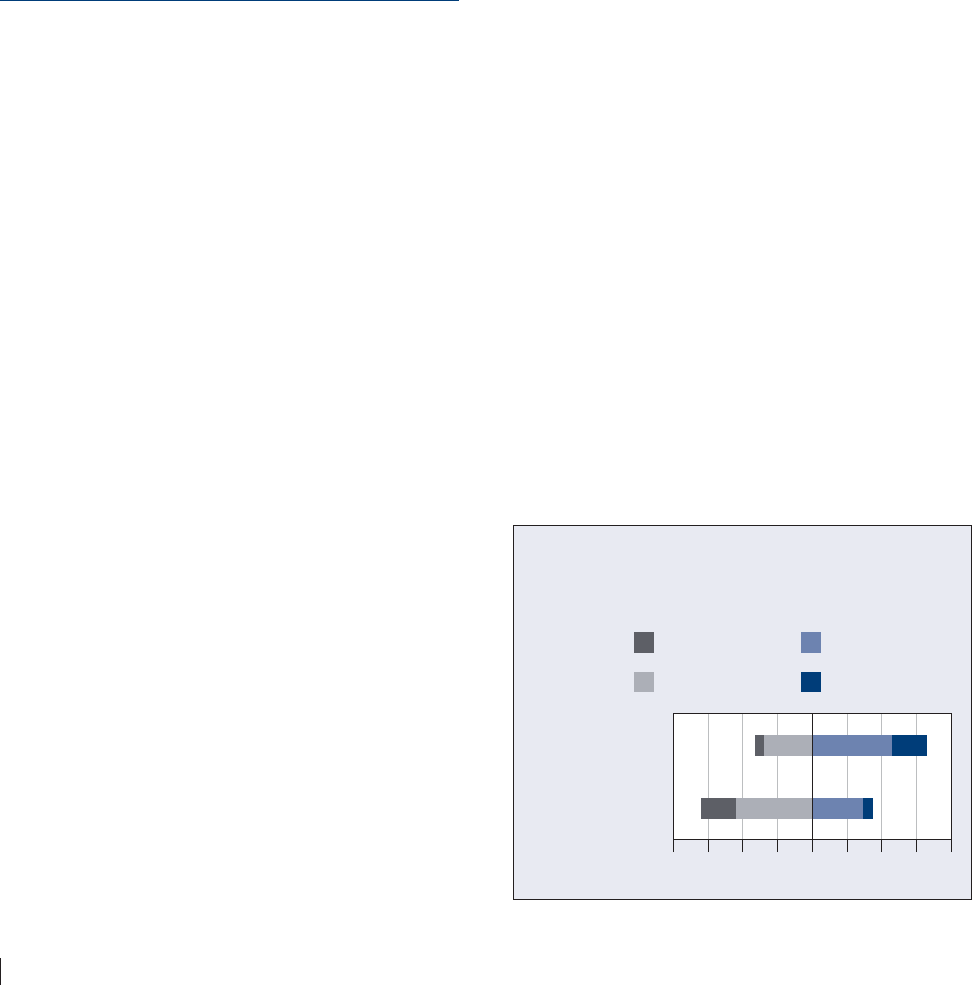

Figure 14 – Economic Inuence

Average rating by respondents in each country on how

much economic influence the U.S./China has in Asia

(0 to 10 scale).

7.0

7.6

7.3

8.0

8.0

8.2

8.4

8.1

7.9

7.6

8.0

7.7

Vietnam

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

U.S.

012345678910

U.S. economic influence

China’s economic influence

Figure 13 – China as Leader of Asia

Percentage in each country who say the following.

Vietnam

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

China

NA

U.S.

0102030405060708090 100

68

27

80

55

10

78

21

35

27

71

56

China will be the leader of Asia

% comfortable with this outcome

17ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

countries (two separate questions), Americans,

Japanese, and South Koreans give China mean

scores in the low to mid range on a 10-point scale

(see Figure 10). Even more surprising, majorities

in the United States (50%), Japan (59%), and South

Korea (56%) rate China as either “somewhat” or

“very ineffective” in resolving the problem of North

Korea’s nuclear weapons program. China also

receives negative assessments of its effectiveness

in helping to manage tensions between Taiwan and

the mainland—55 percent in the United States, 62

percent in Japan, and 53 percent in South Korea

rate it as at least “somewhat ineffective.”

Thus, China’s regional diplomacy is not per-

ceived by respondents to be as effective as is

commonly portrayed in the media and the policy

expert community. Moreover, China’s own efforts

to popularize its ideas about world order and the

conduct of foreign policy do not resonate in Asia.

Large majorities of the publics in each country

have not heard of China’s concept of a “harmo-

nious world” (和谐世界). This is not good news

for the Chinese government, which has invested

considerable effort and resources to popularize

this idea since 2007. Similarly, on a 0 to 10 scale

China receives low scores regarding its ability to

promote its ideas about the best world order from

South Koreans (4.9), Japanese (4.5), and Americans

(4.0). However, China does considerably better

on this question among Indonesians (6.6) and

Vietnamese (6.3).

China receives better, but still mixed ratings on

soft power indicators concerning contemporary

Chinese culture. When asked to assess whether

China’s popular culture has a mainly positive or

negative influence on their own popular culture,

majorities only in Vietnam (80%) and Japan (63%)

say this influence is “somewhat” or “very positive”

(see Figure 15). Citizens in all the countries sur-

veyed have a high regard for China’s “rich cultural

heritage,” with mean scores ranging between 7.8

and 8.6. However, when asked to rate the appeal

of China’s popular culture on a 0 to 10 scale, mean

scores fall around the midpoint—between 5.5 and

6.4—with the notable exception of Vietnam (8.2).

Chinese cultural products do not seem to be suc-

cessful in terms of penetrating the popular culture

of its neighbors. Strong majorities of Japanese and

South Koreas and pluralities of Indonesians say

they “rarely” or “never” view Chinese movies or

television. Only in Vietnam does a plurality view

such Chinese entertainment “every day” (16%) or

“more than once a week” (29%).

One explanation for China’s relatively low

scores on cultural soft power (see Appendix A)

may be that Chinese movies, television programs,

and literature, among other offerings, are almost

exclusively available only in the Chinese language.

Hence their appeal may be limited to overseas

Chinese communities in other Asian countries.

However, majorities in all countries except the

United States feel it is at least somewhat important

for their children to learn Chinese—despite the

fact that China ranks low relative to other coun-

tries as a preferred destination for their children’s

higher education.

In sum, the survey’s findings indicate that

China’s soft power image in Asia and the United

States is more limited than the scholarly and jour-

Figure 15 – Inuence of Chinese Culture

4.6

5.1

4.8

6.5

7.6

48

63

44

50

80

Vietnam

Indonesia

South Korea

Japan

U.S.

012 345678910

0102030405060708090 100

Level of influence Chinese culture has

on each country’s popular culture

(mean score on a 0 to 10 scale)

Percentage in each country who think the

influence of Chinese popular culture on their

country’s popular culture is mainly positive

18 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

nalistic communities have suggested in recent

years. Naturally, China emerges as one of the

stronger regional actors in terms of its economic

power and attractiveness, but this is not matched

by its ability to serve as a regional negotiator and

political and cultural leader.

Perceptions of Japan

Japan boasts the world’s second largest economy

after the United States measured by gross domes-

tic product and third largest after the United States

and China adjusted to purchasing power parity.

Due to China’s rising economic clout in East Asia

and Japan’s slow economic growth throughout the

1990s and until 2003, Japan has been perceived by

some as slowly losing its competitive edge and its

leadership position in the global economy. The

country’s ability to increase its soft power in the

region has been plagued by its military expansions

in the region in the twentieth century. Also, due to

Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s visits

to the Yasukuni shrine, a war shrine containing

the remains of Japanese war criminals, Japan lost

some of its soft power in the region, compromising

its image as a peaceful and cooperative nation.

Japan’s soft power, however, has been helped

by admiration from others for its technologically

advanced economy and its highly educated work-

force. Some of its cultural exports have also gained

recognition in the region. Japanese cuisine and

manga have become known and sought around

the world, and some of its music, films, and ani-

mation have become popular in the region. Its

diplomatic efforts have been recognized and val-

ued, especially by Indonesians and Vietnamese.

While some have expressed skepticism about

Japan’s soft power in the region and its ability to

expand it in the face of a growing China, our data

show that the country is still greatly admired for

its advanced economy and that the hostility for its

wartime actions is not as prominent amongst its

neighbors as one might expect.

Overall, feelings towards Japan on a 0 to 100

scale are mainly positive. The lowest score comes

from the Chinese, who give Japan their low-

est rating of 46, slightly below the neutral point.

Koreans give Japan a neutral rating. Americans,

Indonesians, and Vietnamese register much

warmer feelings, giving Japan their warmest rat-

ings of any country asked about (58, 66, and 68,

respectively). Japan’s overall influence in Asia

is regarded as at least “somewhat positive” by

majorities in all countries polled. There is greater

disagreement regarding perceptions of Japanese

economic influence in Asia. Indonesians and

Vietnamese rank Japan first (along with the United

States) in terms of economic influence in Asia, but

Chinese and South Koreans give Japan the lowest

relative ratings among the major powers.

Despite the fact that Japan is not seen as tre-

mendously influential economically, it ranks very

well on a variety of other economic soft power indi-

cators. Japan’s economic Soft Power Index score

takes the top spot among Americans, Indonesians,

and Vietnamese and the second place among

Chinese and Koreans (see Appendix A).

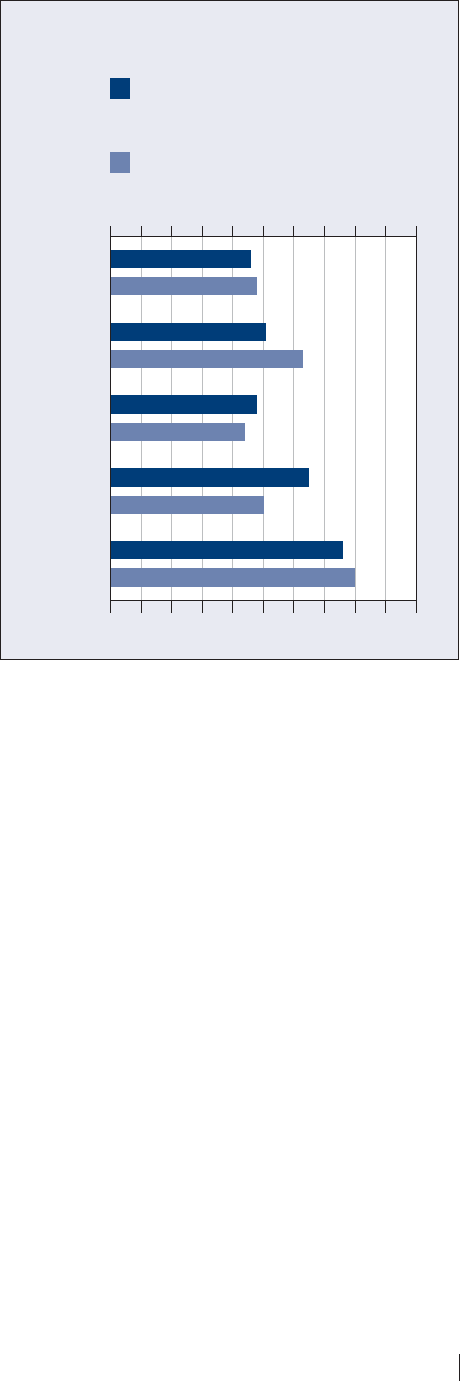

Majorities of respondents in all countries

say that knowing a product is made in Japan

increases the likelihood they will buy the product

(see Figure 16). When it comes to quality of prod-

ucts, Japan gets the highest rating of any other

country’s products on a 0 to 10 scale from South

Koreans, Indonesians, and Vietnamese. It gets the

second highest from Americans and Chinese (see

Figure 16).

This high level of trust in the quality of

Japan’s products by Indonesians and Vietnamese

extends to trust in its companies. Thirty percent

of Indonesians and 31 percent of Vietnamese

believe Japanese companies make a very positive

contribution in their countries. These percentages

are higher than that for any other country. This

confidence in Japan’s technological prowess and

economic strength is also expressed in the will-

ingness of its Asian neighbors to enter into free

trade agreements with Japan. Seventy-nine per-

cent of Chinese and 74 percent of South Koreans

believe they should have a Free Trade Agreement

with Japan. These percentages, however, are lower

than those who think their country should have

a free trade agreement with the United States

and ASEAN.

19ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

A further testament to Japan’s economic

attractiveness is the perception that the country

helps other Asian countries develop economi-

cally. Japan receives the highest ratings relative

to the other major powers on a 0 to 10 scale from

Indonesians (7.4) and Vietnamese (7.8) on this

indicator. In terms of the importance of overall

economic relations with Japan, both the United

States and Indonesia rank their economic rela-

tionship with Japan as more important than any

other country surveyed.

17

Unlike its economy, Japan’s political system

and the way it conducts its foreign policy in the

region is not viewed as particularly effective by

others. When asked to rate the level of respect for

the sovereignty of other Asian nations on a 0 to 10

17. Americans rate the importance of economic relations

with Japan higher than that of the EU and China.

scale, Japan receives higher ratings than any other

country only from Americans and Indonesians.

South Koreans rate Japan on the same level as

China (4.9) on this indicator, but higher than the

United States (4.8).

Similar to its political soft power, Japan’s

regional diplomacy receives somewhat mixed

ratings. On the question of the use of diplomacy

to resolve problems in Asia, Americans and

Indonesians again give Japan their highest rat-

ings (6.5 and 7.1, respectively). Chinese and South

Koreans rank Japan’s use of diplomacy around the

midpoint (5.4 and 5.5, respectively). Japan’s efforts

to solve the North Korea nuclear issue are consid-

ered “very” or “somewhat effective” by a slight

majority only in China. Japan’s diplomatic efforts

in managing tensions between mainland China

and Taiwan are considered “very” or “somewhat

ineffective” by majorities or pluralities in all sur-

veyed countries except the United States, where a

plurality thinks Japan has been at least “somewhat

effective.” Apparently, Japan’s attempts at regional

diplomacy have not resonated with the Chinese

and South Korean publics, and it emerges as one of

the weaker aspects of Japan’s overall soft power.

One surprising finding is that Japan’s govern-

ment receives above average ratings across the

board for its effectiveness in promoting its poli-

cies in the region. Lower ratings might have been

expected because of Japan’s territorial disputes

with China and South Korea over islands in the

Pacific and because of the loud protests in recent

years in both countries over visits to the Yasukuni

shrine as well as the approval of a Japanese history

textbook glossing over Japanese wartime aggres-

sion. In terms of resolving the territorial disputes,

none of the Chinese, South Korean, or Japanese

publics has a conciliatory attitude. When it comes

to the Yasukuni shrine visits, both the Chinese

and Korean publics agree that they should pro-

test them in some manner (only 2 percent in each

country think their country should not protest

these visits).

Unlike attitudes towards its politics and

diplomacy, admiration for Japan’s human capital

earns the country higher marks. On most indi-

Figure 16 – Appeal/Quality of Japanese Products

Average rating by respondents in each country

(0 to 10 scale) on the following.

8.7

8.9

7.5

8.2

6.6

6.6

8.1

5.6

7.5

5.5

7.0

U.S.

China

South Korea

Japan

NA

Indonesia

Vietnam

012345678910

Influence on buying decision of

products being made in Japan

(0 meaning less likely to buy,

10 meaning more likely to buy)

Quality of products made in Japan

(0 meaning extremely poor, 10

meaning extremely good quality)

20 ASIA SOFT POWER SURVEY 2009 EDITION

cators, such as the level of education of Japan’s

population, the quality of its universities, and its

advanced science and technology, Japan is ranked

first by Americans and Vietnamese and second

usually only to the United States by Chinese, South

Koreans, and Indonesians (see Figure 17).

Perceptions of the cultural component of

Japan’s soft power are also mixed. Majorities in

every country except South Korea (which is split)

think that the influence of Japanese popular

culture is either “very” or “somewhat positive.”

Overall, majorities in all countries except South

Korea believe the spread of Japan’s cultural influ-

ence in Asia is mainly a “good thing” rather than

a “bad thing.”

Yet there is little agreement as to whether the

influence of Japan’s popular culture on the respon-

dents’ culture is positive or negative. In South

Korea, only a weak plurality believes Japan’s influ-

ence on Korea’s popular culture is positive. A solid

majority of Chinese (59%) think that the influ-

ence of Japan’s popular culture is mostly positive,

but this is the lowest relative rating given by the

Chinese (between China, the United States, Japan,

and South Korea). While South Koreans may not

view Japan’s cultural influence as very positive,

they give Japan the second highest ranking of

appeal of its popular culture after that of American

popular culture. Vietnamese rank the appeal

of Japanese culture after that of China. Japan is

ranked second by almost every country on indica-

tors such as the appeal of its popular culture, the

richness of its cultural heritage, and its attractive-

ness as an international tourist destination. On

most cultural indicators, the two Southeast Asian

countries rank Japan after China.

Generally, Japanese soft power is felt through-

out the region but is limited on the diplomatic

front. While the survey finds that the United

States has the greatest power of attraction in

almost all surveyed countries, Japan usually ranks

close behind.

Perceptions of South Korea

South Korea has high aspirations for its role in

Northeast Asia and sees itself as a pivotal player

in the politics of the region, acting as broker, bal-

ancer, or hub of the great powers that surround it.

South Korea has taken an active role in promoting

regional integration, seeking trade agreements

with its allies, and looking to actively mediate dis-

putes between the United States and North Korea

and potential tensions between China and Japan.

However, being surrounded by great powers,

South Korea has struggled to gain recognition for

its achievements and dynamism. South Korea is

the thirteenth largest economy in the world, but

is physically located between the second (Japan)

and the fourth (China) and is an ally of the United

States. South Korea’s products and technology are

becoming trusted international brand names, but

Korea still lacks Japan’s “Gross National Cool.”

Regionally, South Korea has developed a

closer relationship with China both economically