SURVEY BRIEF

FEBRUARY 2019

Health Insurance Coverage

Eight Years Aer the ACA:

Fewer Uninsured

Americans and

Shorter Coverage

Gaps, But More

Underinsured

Sara R. Collins

Vice President

The Commonwealth Fund

Herman K. Bhupal

Program Associate

The Commonwealth Fund

Michelle M. Doty

Vice President

The Commonwealth Fund

What does health insurance coverage look like for Americans today, more than eight

years aer the Aordable Care Act’s passage? In this brief, we present findings from the

Commonwealth Fund’s latest Biennial Health Insurance Survey to assess the extent

and quality of coverage for U.S. working-age adults. Conducted since 2001, the survey

uses three measures to gauge the adequacy of people’s coverage:

• whether or not they have insurance

• if they have insurance, whether they have experienced a gap in their coverage in

the prior year

• whether high out-of-pocket health care costs and deductibles are causing them to

be underinsured, despite having continuous coverage throughout the year.

As the findings highlighted below show, the greatest deterioration in the quality and

comprehensiveness of coverage has occurred among people in employer plans. More

than half of Americans under age 65 — about 158 million people — get their health

insurance through an employer, while about one-quarter either have a plan purchased

through the individual insurance market or are enrolled in Medicaid.

1

Although the

ACA has expanded and improved coverage options for people without access to a job-

based health plan, the law largely le the employer market alone.

2

SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS

Today, 45 percent of U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 are inadequately insured — nearly the

same as in 2010 — though important shis have taken place.

Compared to 2010, many fewer adults are uninsured today, and the duration of

coverage gaps people experience has shortened significantly.

Despite actions by the Trump administration and Congress to weaken the ACA, the

adult uninsured rate was 12.4 percent in 2018 in this survey, statistically unchanged

from the last time we fielded the survey in 2016

.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 2

More people who have coverage are underinsured now than

in 2010, with the greatest increase occurring among those in

employer plans.

People who are underinsured or spend any time uninsured

report cost-related problems getting care and diculty paying

medical bills at higher rates than those with continuous,

adequate coverage.

Federal and state governments could enact policies to extend

the ACA’s health coverage gains and improve the cost protection

provided by individual-market and employer plans.

The 2018 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Heath Insurance Survey

included a nationally representative sample of 4,225 adults ages 19

to 64. SSRS conducted the telephone survey between June 27 and

November 11, 2018.

3

(See “How We Conducted This Study” for more

detail.)

WHO IS UNDERINSURED?

In this analysis, we use a measure of underinsurance that accounts

for an insured adult’s reported out-of-pocket costs over the course

of a year, not including insurance premiums, as well as his or her plan

deductible. (The measure was first used in the Commonwealth Fund’s

2003 Biennial Health Insurance Survey.*) These actual expenditures

and the potential risk of expenditures, as represented by the deductible,

are then compared with household income. Specifically, we consider

people who are insured all year to be underinsured if:

• their out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, over

the prior 12 months are equal to 10 percent or more of

household income; or

• their out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, over

the prior 12 months are equal to 5 percent or more of

household income for individuals living under 200 percent

of the federal poverty level ($24,120 for an individual or

$49,200 for a family of four); or

• their deductible constitutes 5 percent or more of

household income.

The out-of-pocket cost component of the measure is only triggered

if a person uses his or her plan to obtain health care. The deductible

component provides an indicator of the financial protection the plan

offers and the risk of incurring costs before someone gets health

care. The definition does not include other dimensions of someone’s

health plan that might leave them potentially exposed to costs, such as

copayments or uncovered services. It therefore provides a conservative

measure of underinsurance in the United States.

* Cathy Schoen et al., “Insured But Not Protected: How Many Adults Are Underinsured?” Health

Affairs Web Exclusive, published online June 14, 2005.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 3

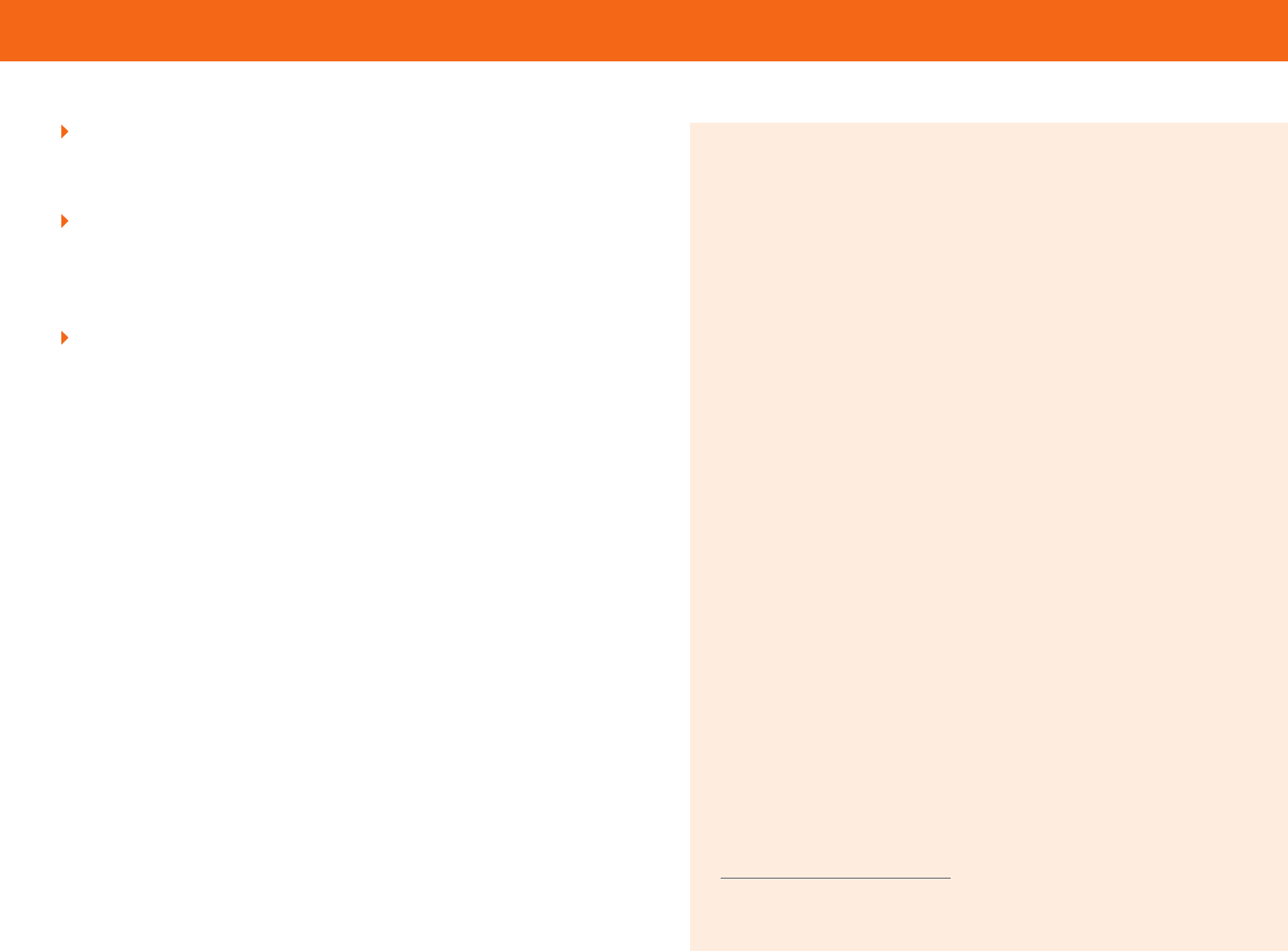

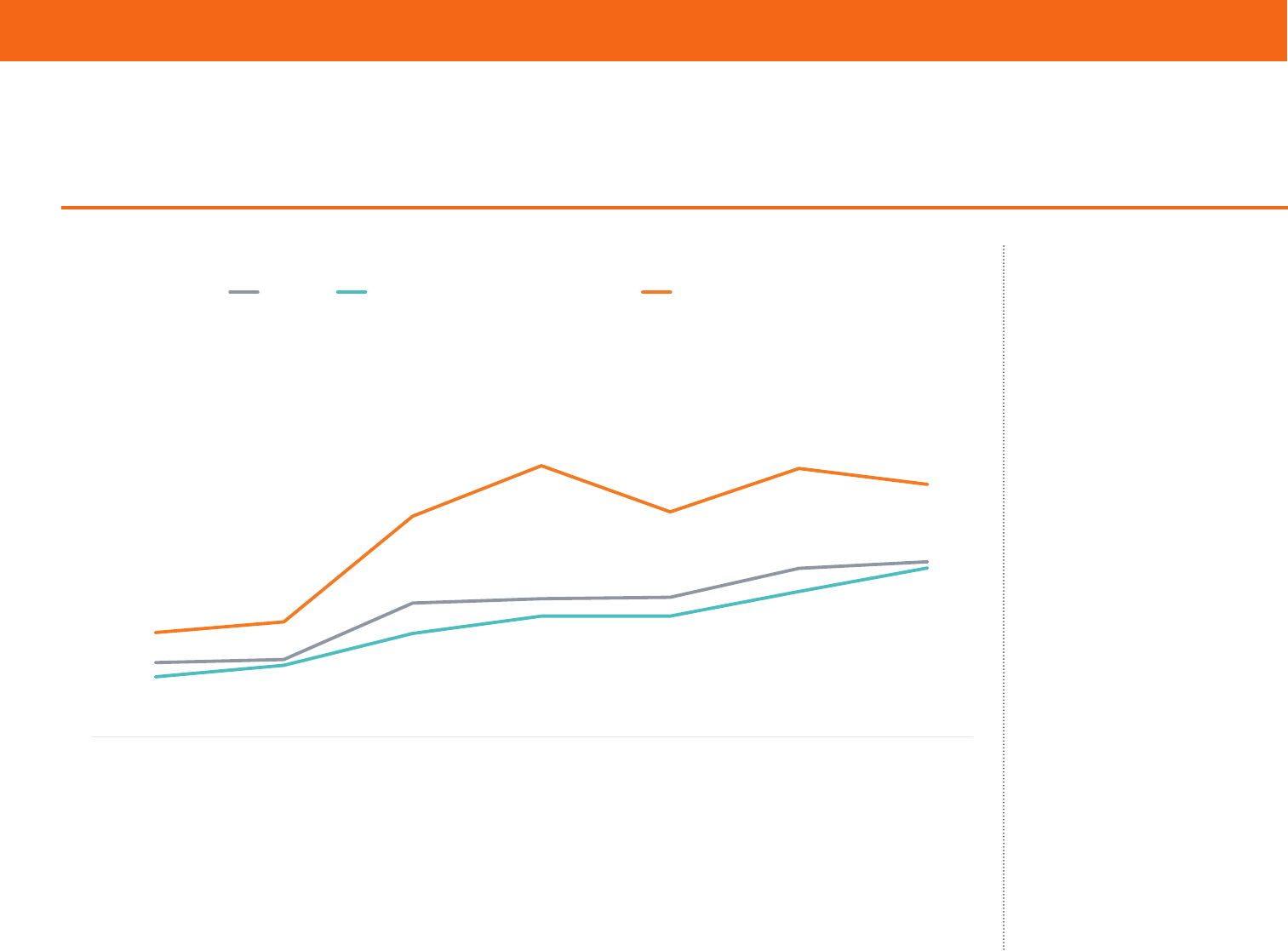

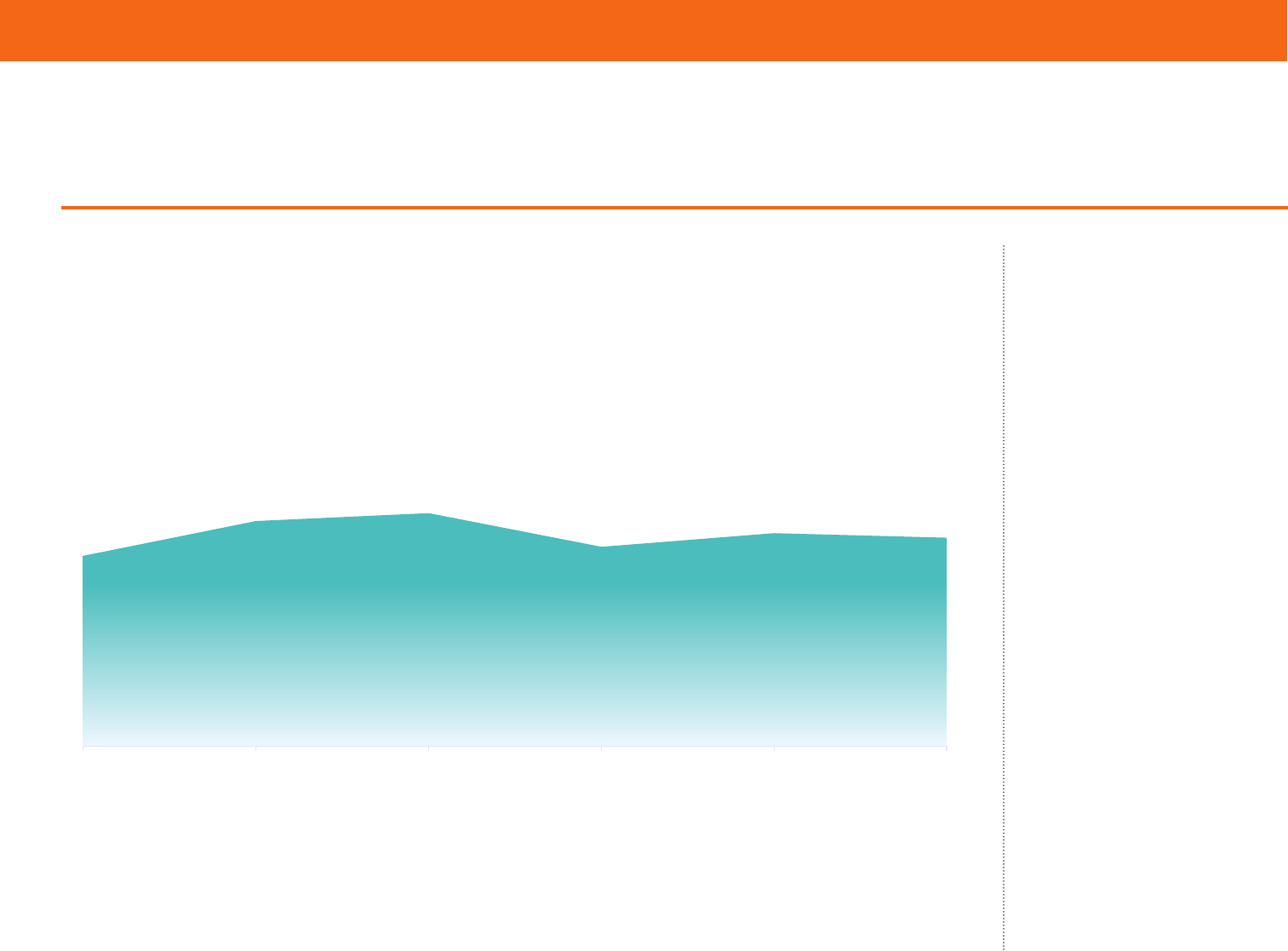

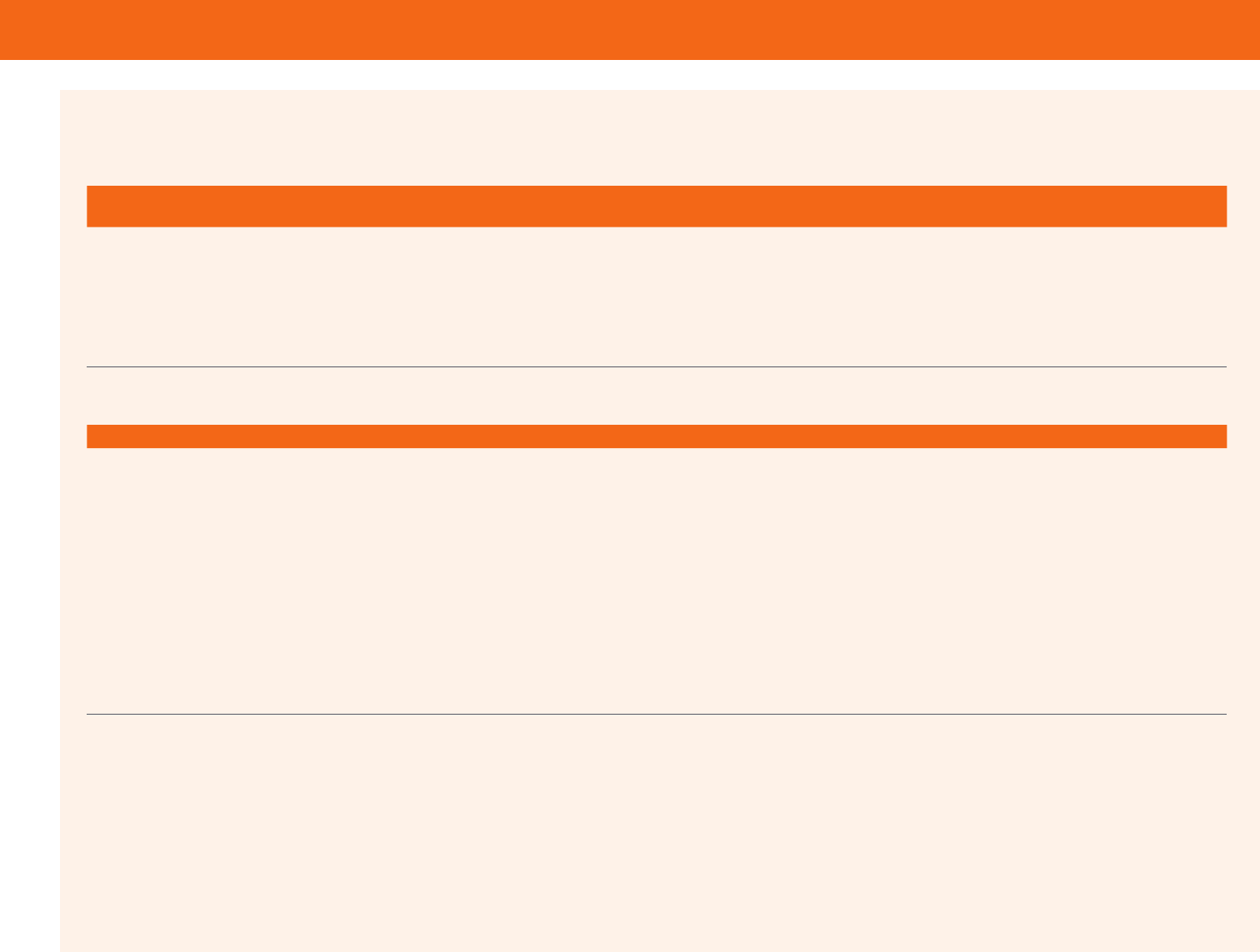

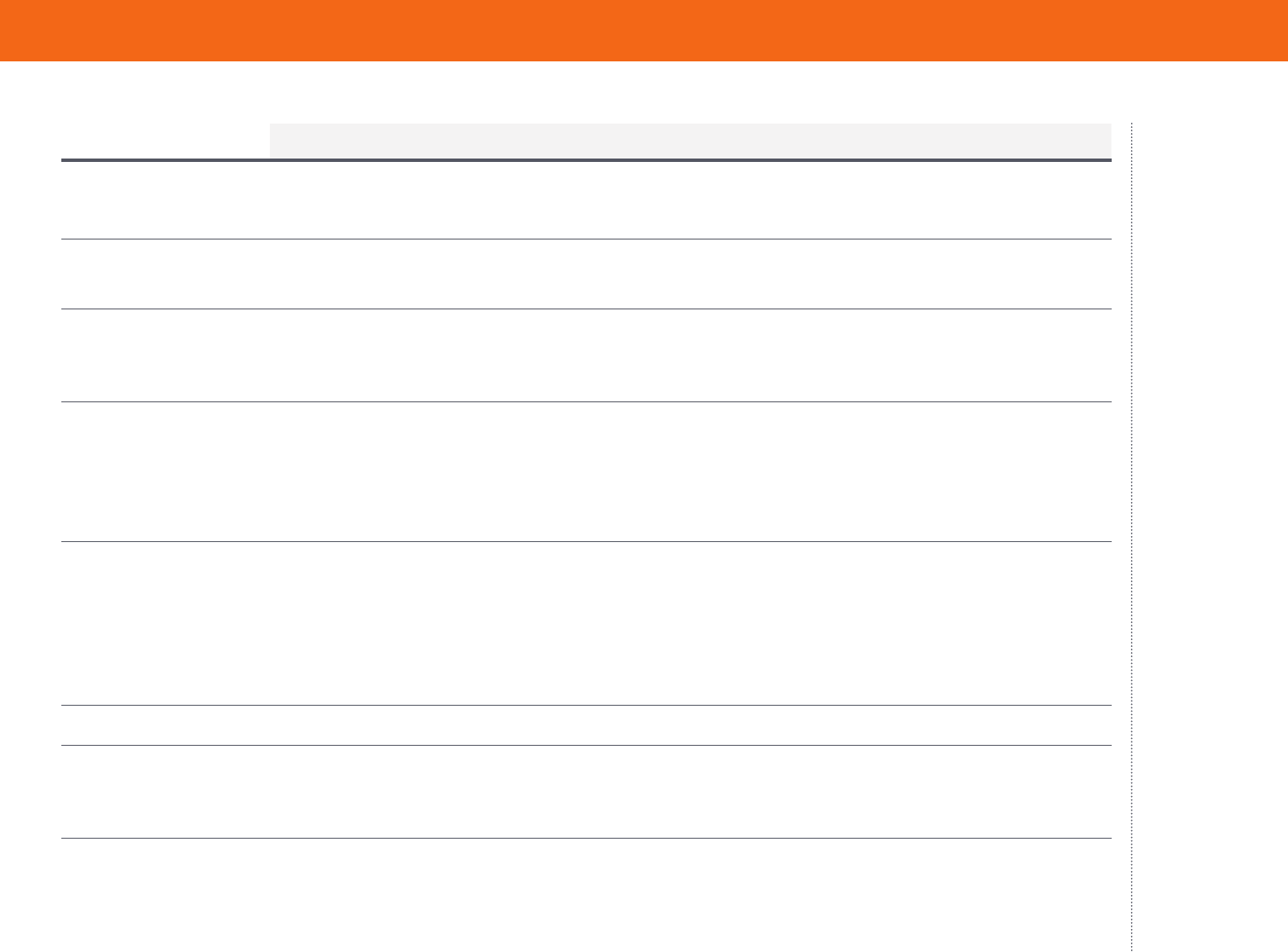

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

17%

18%

20%

19%

16%

12%

12%

9%

9%

8%

10%

13%

10%

10%

9%

9%

16%

16%

17%

22%

23%

65%

63%

56%

54% 55%

56%

55%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Since the ACA, Fewer Adults Are Uninsured, but More Are Underinsured

Percent of adults ages 19–64

Notes: “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were

insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to the survey field date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the

survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Insured all year, not underinsured

Insured now, had a coverage gap

Insured all year, underinsured

Uninsured now

Notes: “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding

premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200%

of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of

the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to the survey eld date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Since the ACA, Fewer Adults Are Uninsured, but More Are Underinsured

Compared to 2010, when

the ACA became law, fewer

people today are uninsured,

but more people are

underinsured. Of the 194

million U.S. adults ages 19 to

64 in 2018, an estimated 87

million, or 45 percent, were

inadequately insured (see

Tables 1 and 2).

Despite actions by the

Trump administration and

Congress to weaken the

ACA, our survey found no

statistically significant change

in the adult uninsured rate

by late 2018 compared to

2016 (Table 3). This finding

is consistent with recent

federal surveys, but other

private surveys (including

other Commonwealth Fund

surveys) have found small

increases in uninsured rates

since 2016 (see Changes in U.S.

Uninsured Rates Since 2013).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 4

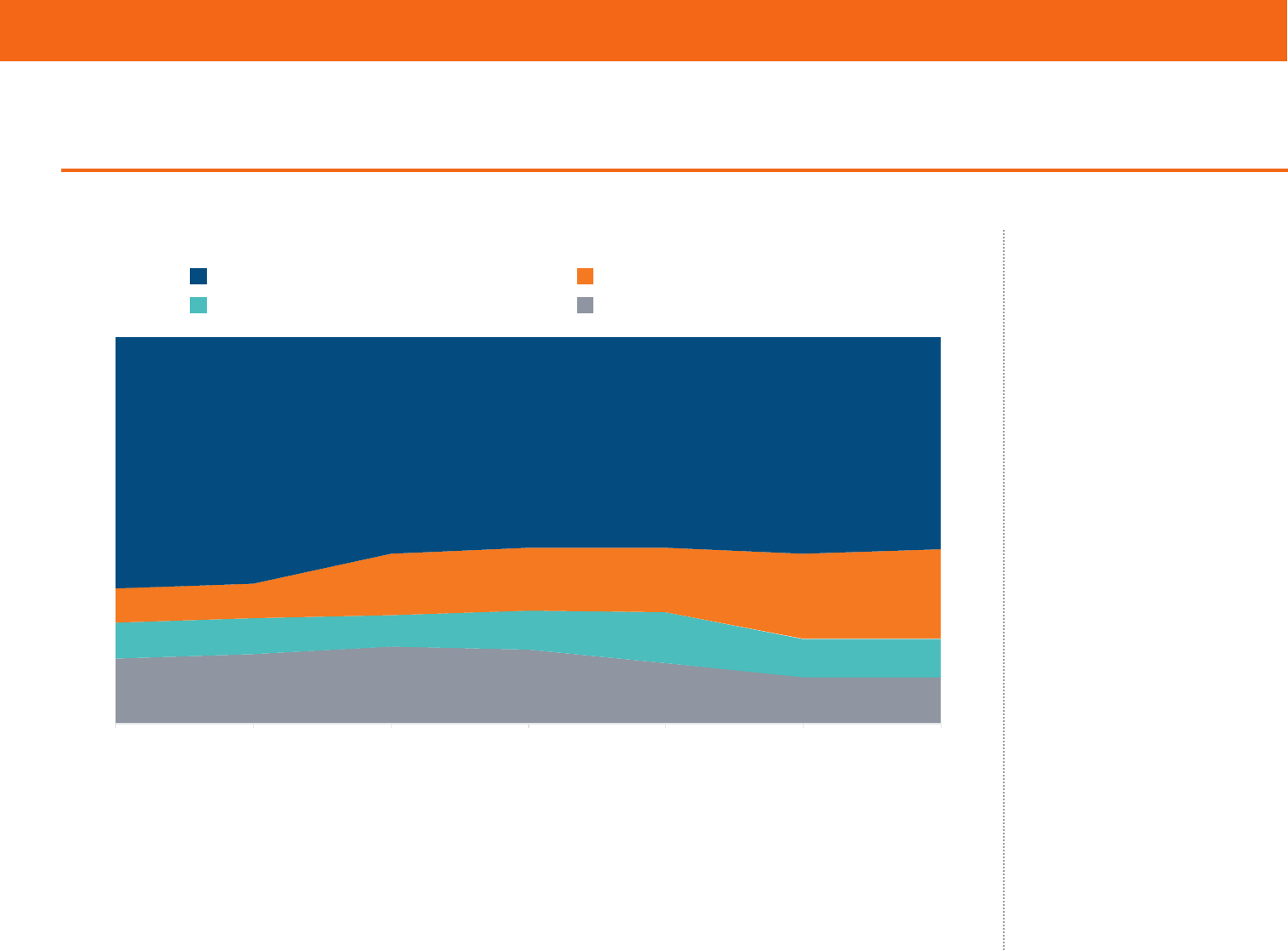

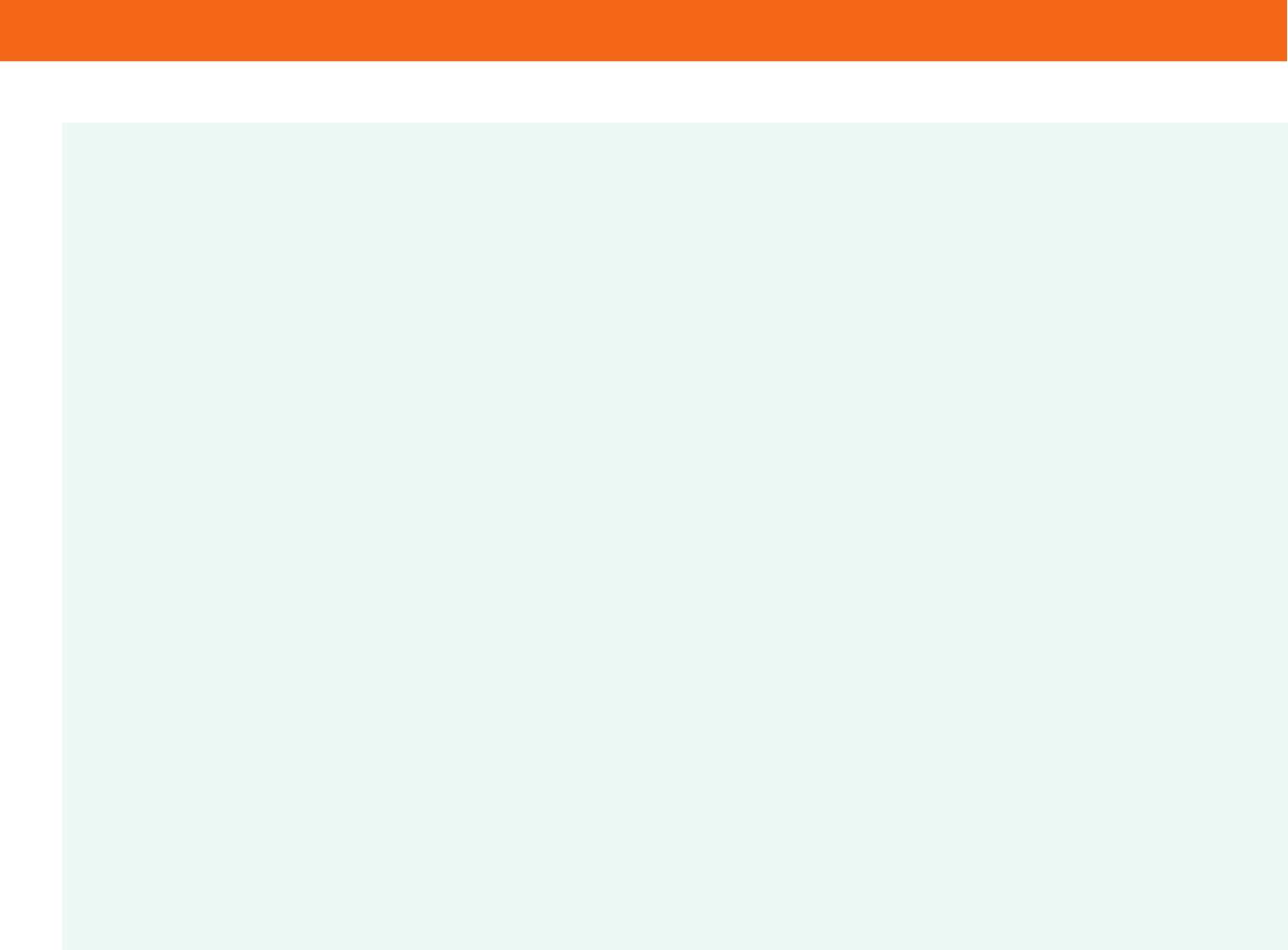

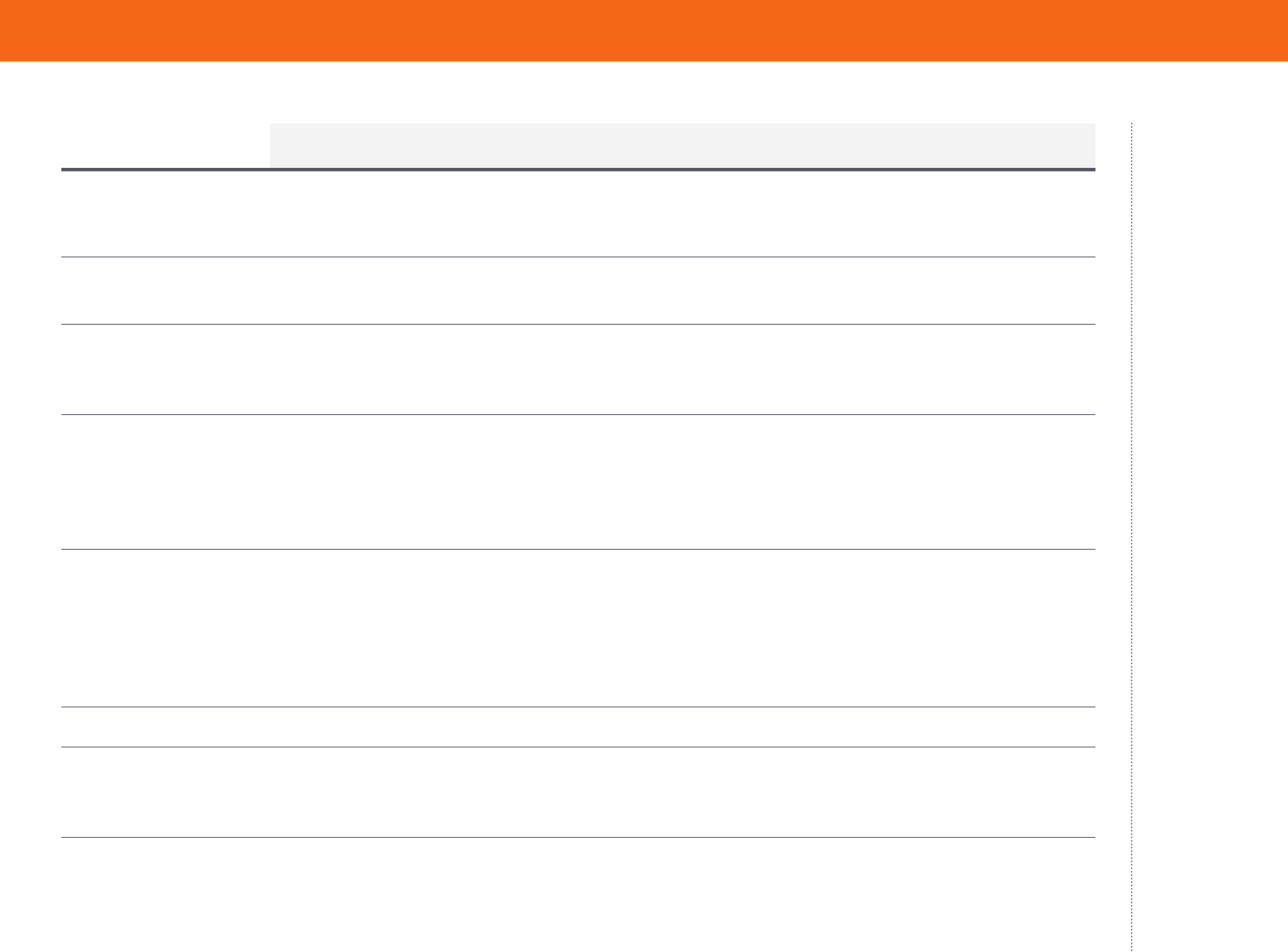

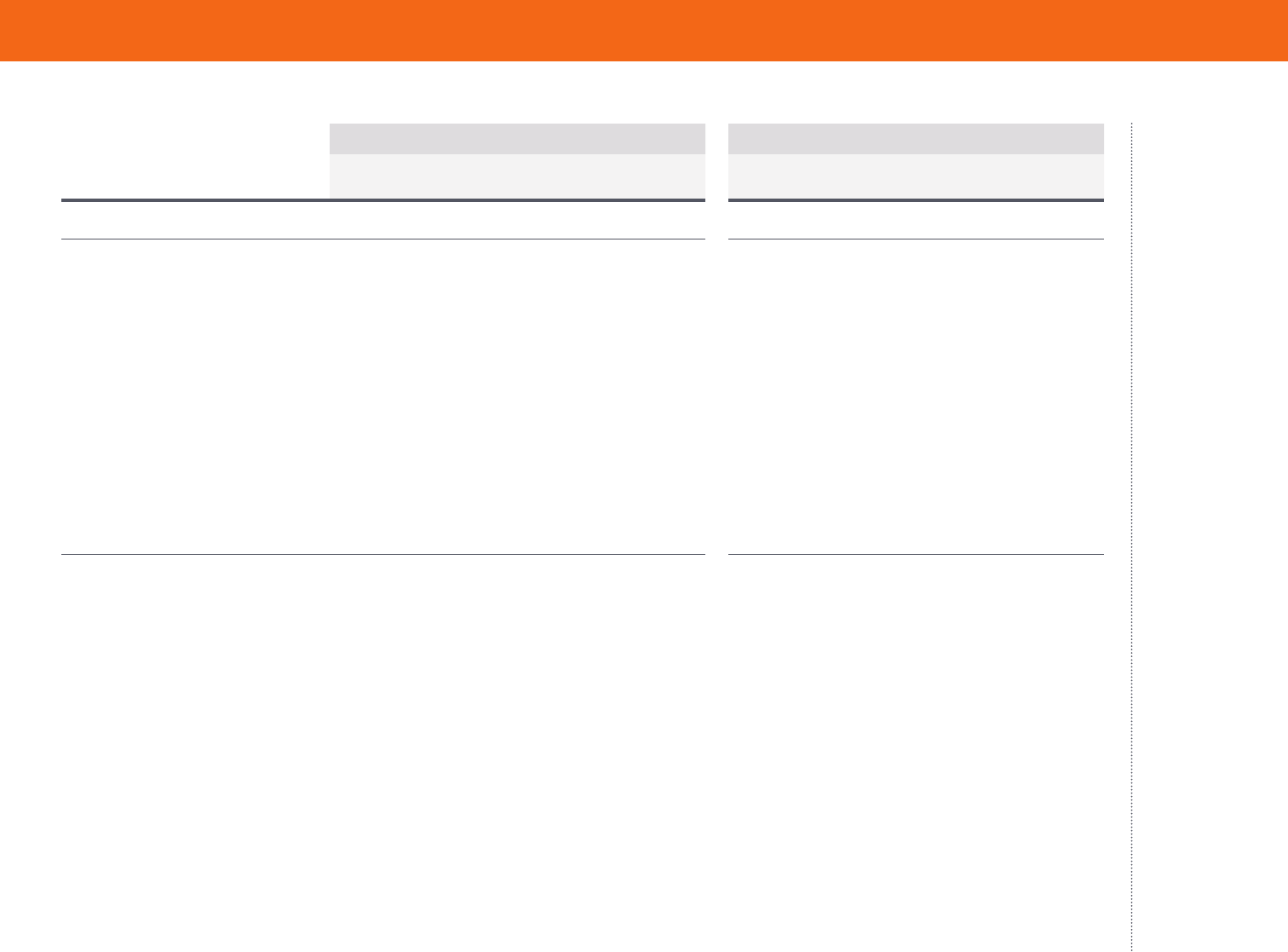

Since the ACA, Gaps in People’s Coverage Have Been Shorter

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2001, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

While there has been

no change since 2010,

statistically speaking, in

the proportion of people

who are insured now but

have experienced a recent

time without coverage,

these reported gaps are

of much shorter duration

on average than they were

before the ACA. In 2018,

61 percent of people who

reported a coverage gap said

it has lasted for six months

or less, compared to 31

percent who said they had

been uninsured for a year

or longer. This is nearly a

reverse of what it was like

in 2012, two years before

the ACA’s major coverage

expansions. In that year,

57 percent of adults with

a coverage gap reported

it was for a year or longer,

while one-third said it was a

shorter gap.

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Since the ACA, Gaps in People’s Coverage Have Been Shorter

65

47

35

38

54

61

25

39

57

55

38

31

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2001 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Coverage gap of 6 months or less Coverage gap of 1 year or more

Percent of adults ages 19–64 insured now but had a coverage gap in past year

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2001, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 5

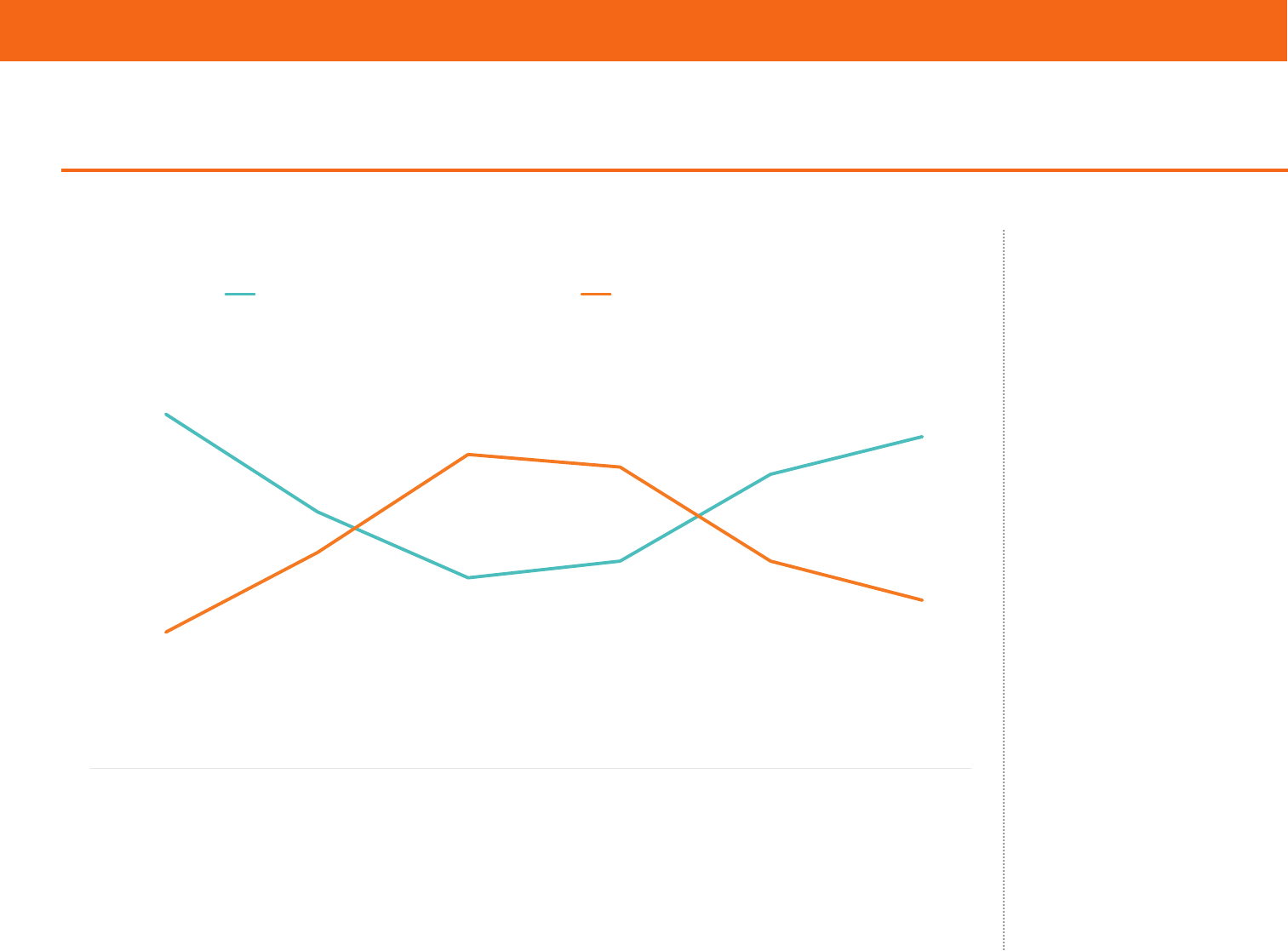

There Has Been Some Improvement in Long-Term Uninsured Rates

There also has been some

improvement in long-term

uninsured rates. Among

adults who were uninsured

at the time of the survey, 54

percent reported they had

been without coverage for

more than two years, down

from 72 percent before the

ACA coverage expansions

went into eect. The share

of those who had been

uninsured for six months or

less climbed to 20 percent,

nearly double the rate prior

to the coverage expansions.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2001, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

There Has Been Some Improvement in Long-Term Uninsured Rates

19

11

12

13

21

20

62

63

72

64

53

54

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2001 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Uninsured for 6 months or less Uninsured for more than 2 years

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2001, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Percent of adults ages 19–64 who are uninsured now

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 6

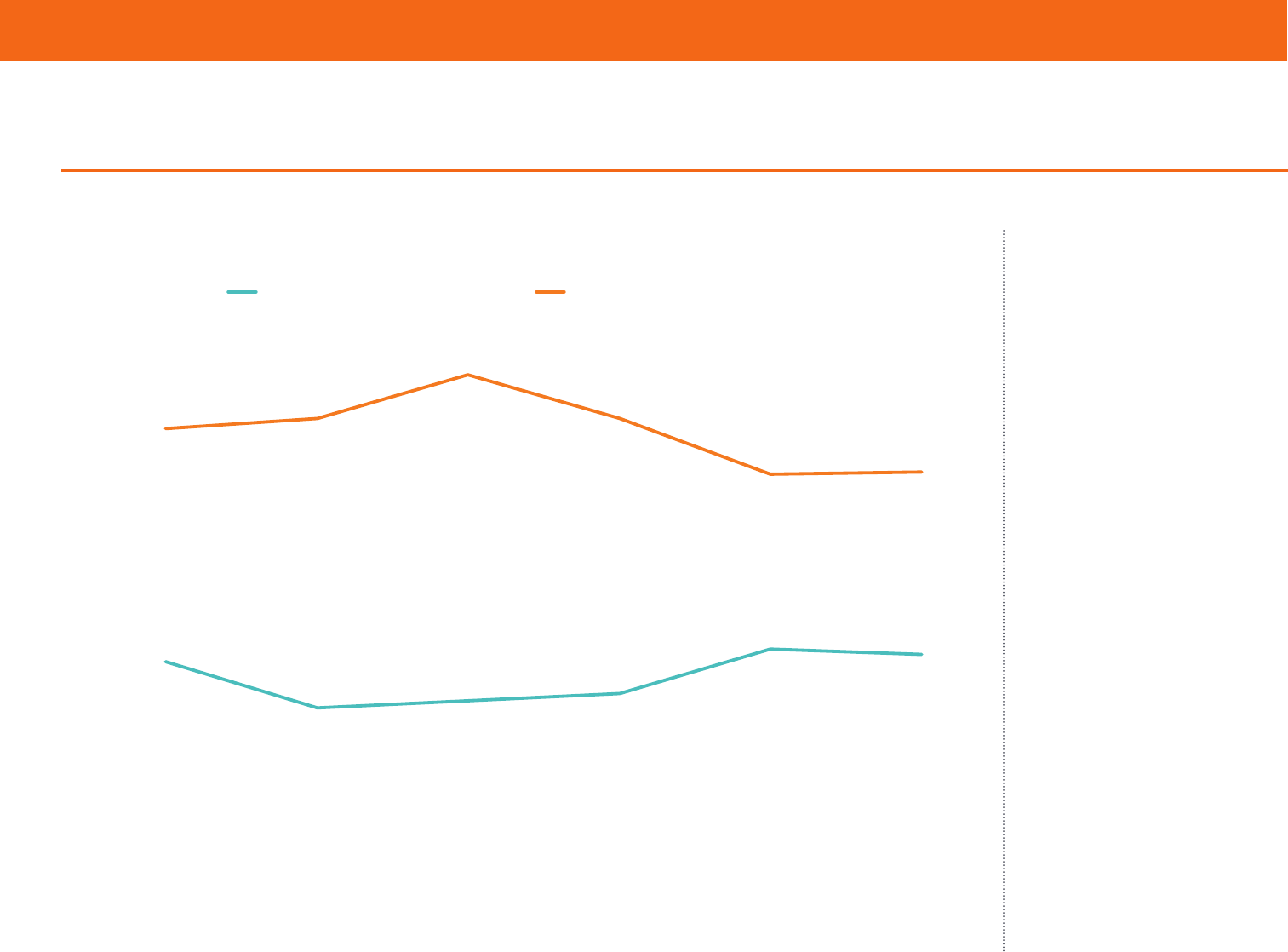

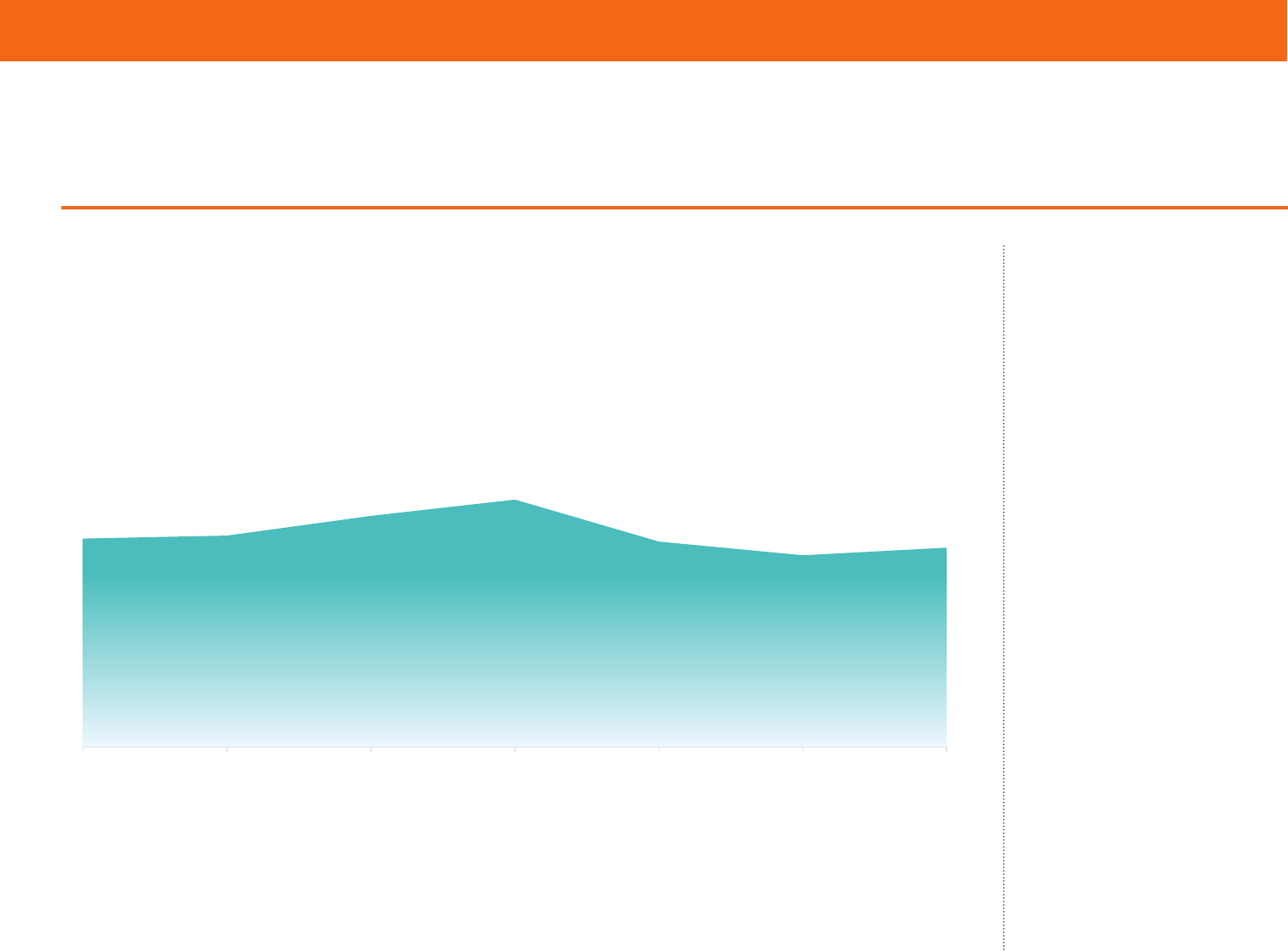

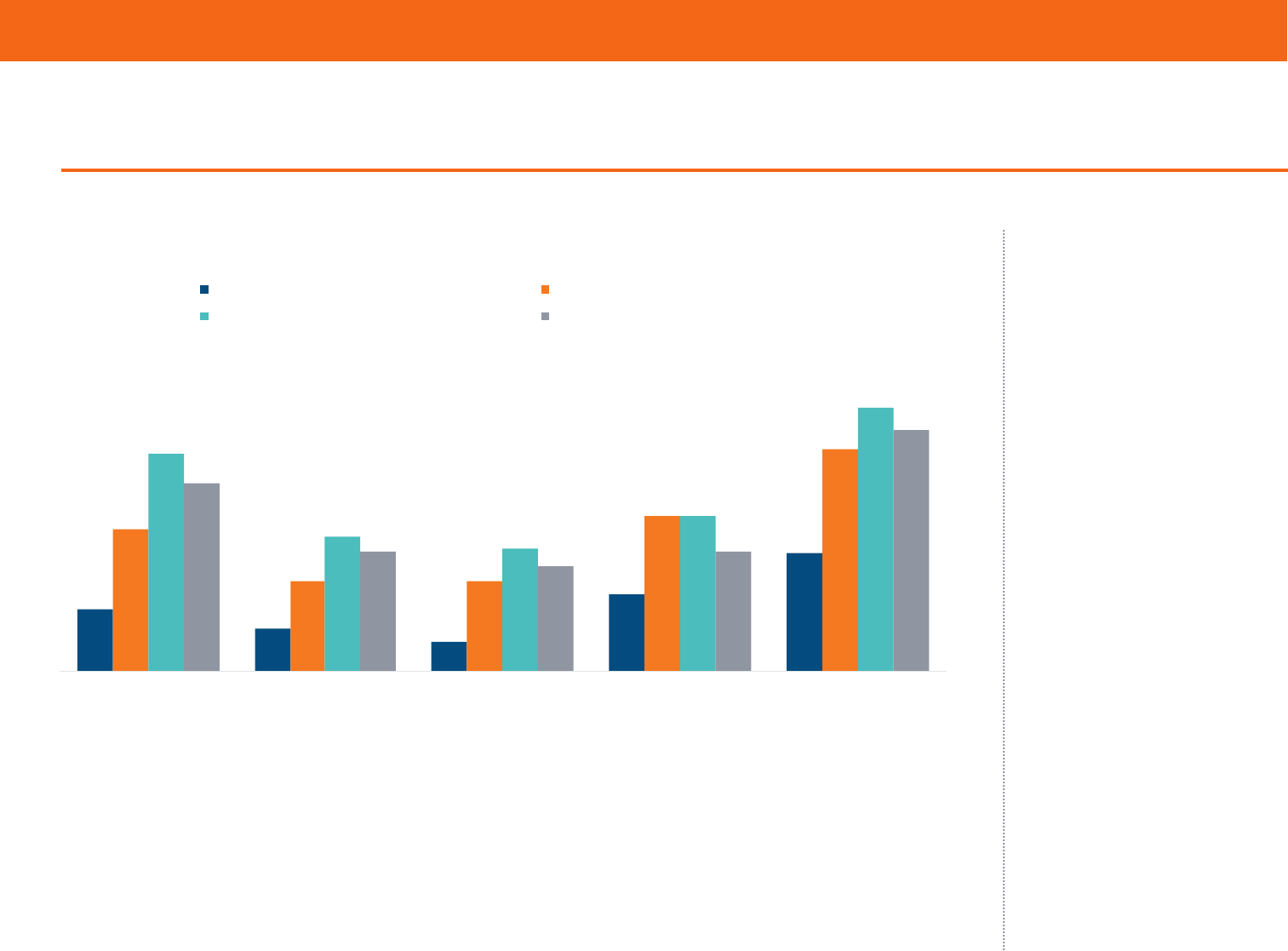

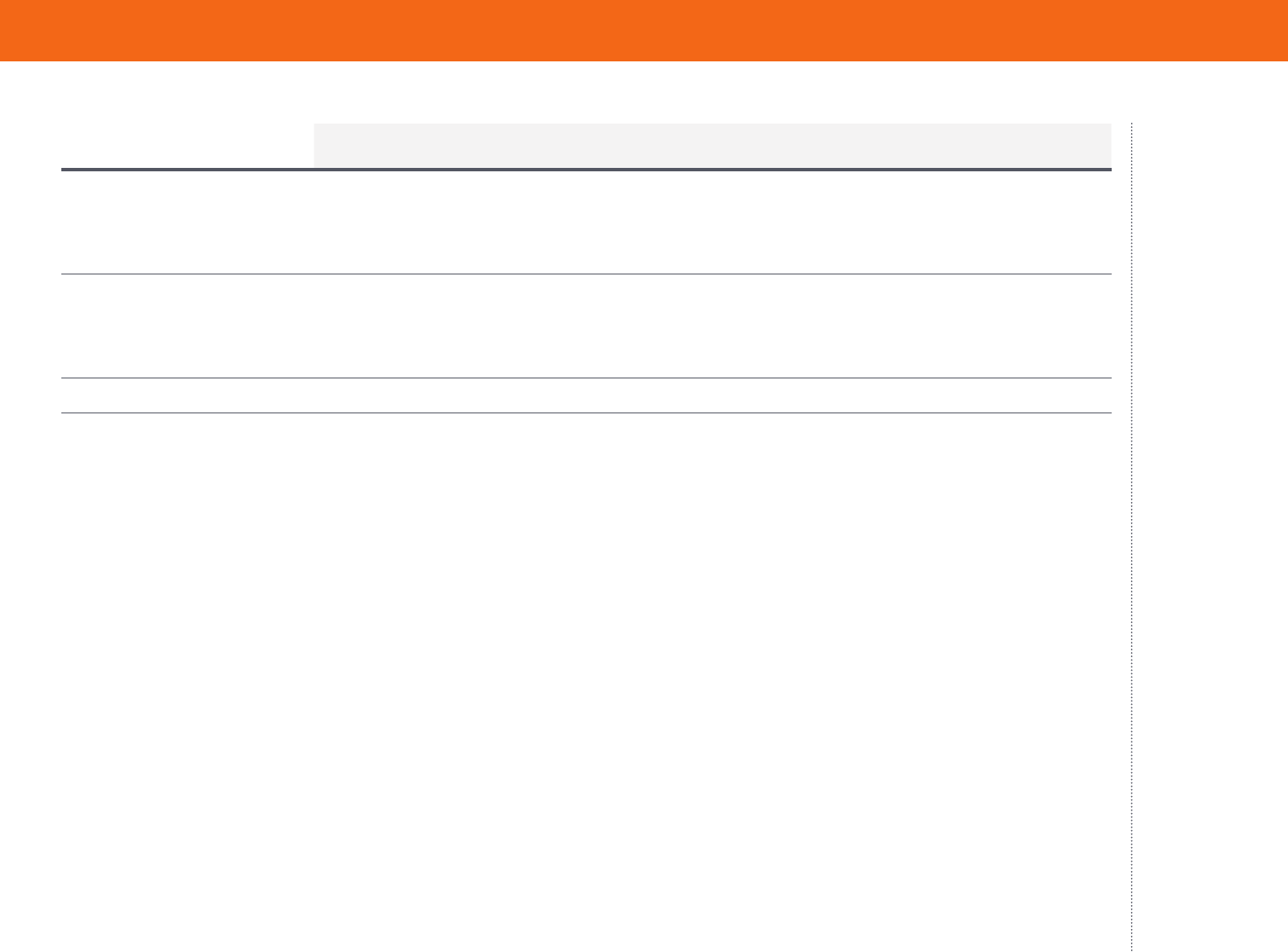

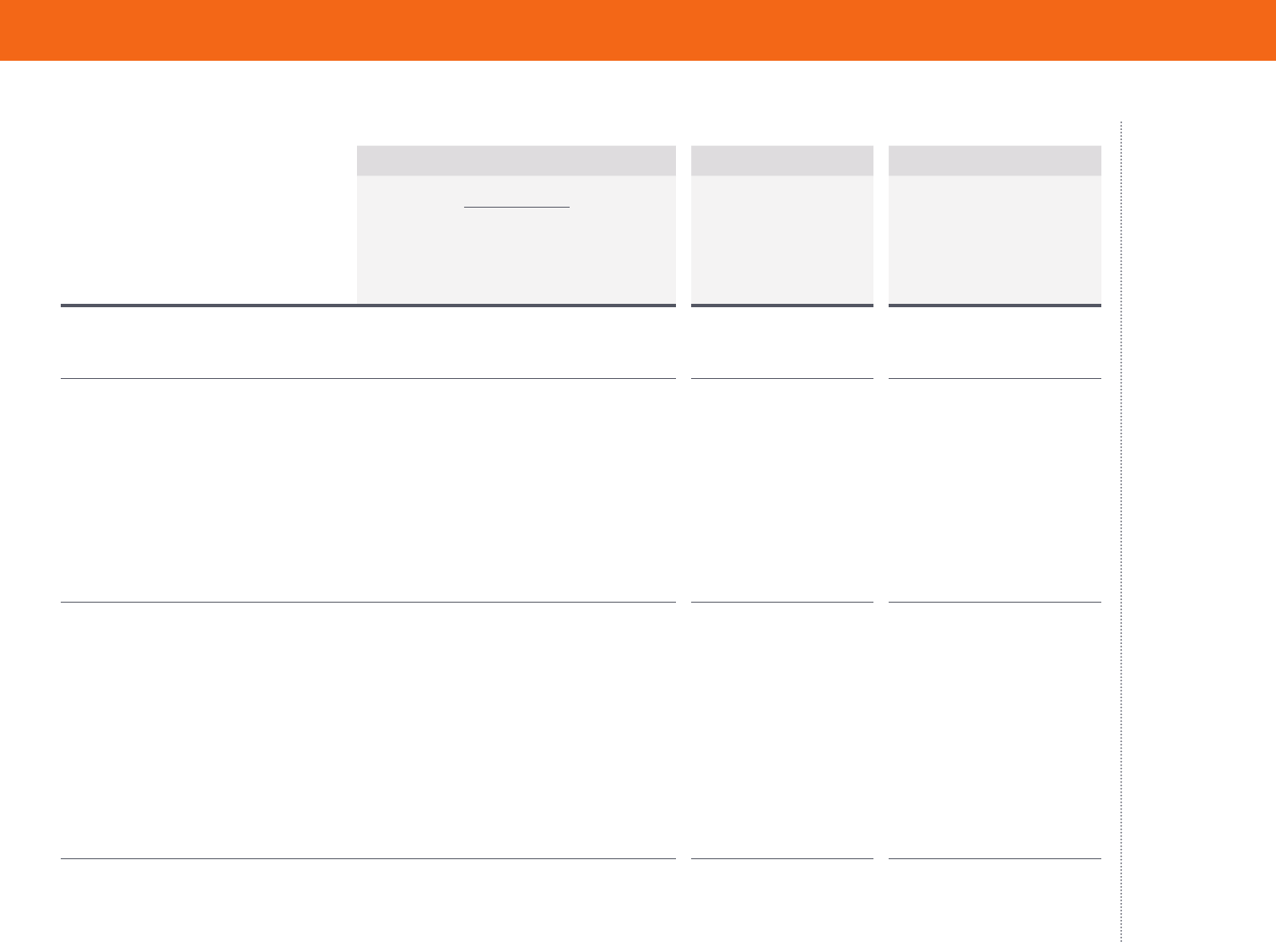

More Adults Are Underinsured, with the Greatest Growth Occurring Among Those

with Employer Coverage

Notes: “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding

premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of

poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. Total includes adults with coverage through Medicaid and Medicare. Respondents may

have had another type of coverage at some point during the year, but had coverage for the entire previous 12 months. ^ For 2014 and 2016,

includes those who get their individual coverage through the marketplace and outside of the marketplace.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Of people who were insured

continuously throughout

2018, an estimated 44 million

were underinsured because

of high out-of-pocket costs

and deductibles (Table 1).

This is up from an estimated

29 million in 2010 (data

not shown). The most

likely to be underinsured

are people who buy plans

on their own through the

individual market including

the marketplaces. However,

the greatest growth in the

number of underinsured

adults is occurring among

those in employer health

plans.

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

More Adults Are Underinsured, with the Greatest Growth Occurring Among Those with

Employer Coverage

Notes: “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. Total includes adults with coverage through Medicaid and

Medicare. Respondents may have had another type of coverage at some point during the year, but had coverage for the entire previous 12 months. ^ For 2014 and 2016, includes those who get their

individual coverage through the marketplace and outside of the marketplace.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

12

13

22

23

23

28

29

10

12

17

20

20

24

28

17

19

37

45

37

44

42

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Total Employer-provided coverage Individual coverage^

Percent of adults ages 19–64 insured all year who were underinsured

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 7

Why Are Insured Americans Spending So Much of Their Income

on Health Care Costs?

Several factors may be contributing to high underinsured rates among adults in individual market plans and rising

rates in employer plans:

1. Although the Aordable Care Act’s reforms to the

individual market have provided consumers with greater

protection against health care costs, many moderate-

income Americans have not seen gains. The ACA’s essential

health benefits package, cost-sharing reductions for lower-

income families, and out-of-pocket cost limits have helped

make health care more aordable for millions of Americans.

But while the cost-sharing reductions have been particularly

important in lowering deductibles and copayments for

people with incomes under 250 percent of the poverty level

(about $62,000 for a family of four), about half of people who

purchase marketplace plans, and all of those buying plans

directly from insurance companies, do not have them.

4

2. The bans against insurers excluding people from

coverage because of a preexisting condition and rating

based on health status have meant that individuals with

greater health needs, and thus higher costs, are now

able to get health insurance in the individual market.

Not surprisingly, the survey data show that people with

individual market coverage are somewhat more likely to have

health problems than they were in 2010, which means they

also have higher costs.

3. While plans in the employer market historically have

provided greater cost protection than plans in the

individual market, businesses have tried to hold down

premium growth by asking workers to shoulder an

increasing share of health costs, particularly in the

form of higher deductibles.

5

While the ACA’s employer

mandate imposed a minimum coverage requirement on large

companies, the requirement amounts to just 60 percent of

typical person’s overall costs. This leaves the potential for

high plan deductibles and copayments.

4. Growth in Americans’ incomes has not kept pace with

growth in health care costs. Even when health costs rise

more slowly, they can take an increasingly larger bite out of

incomes.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 8

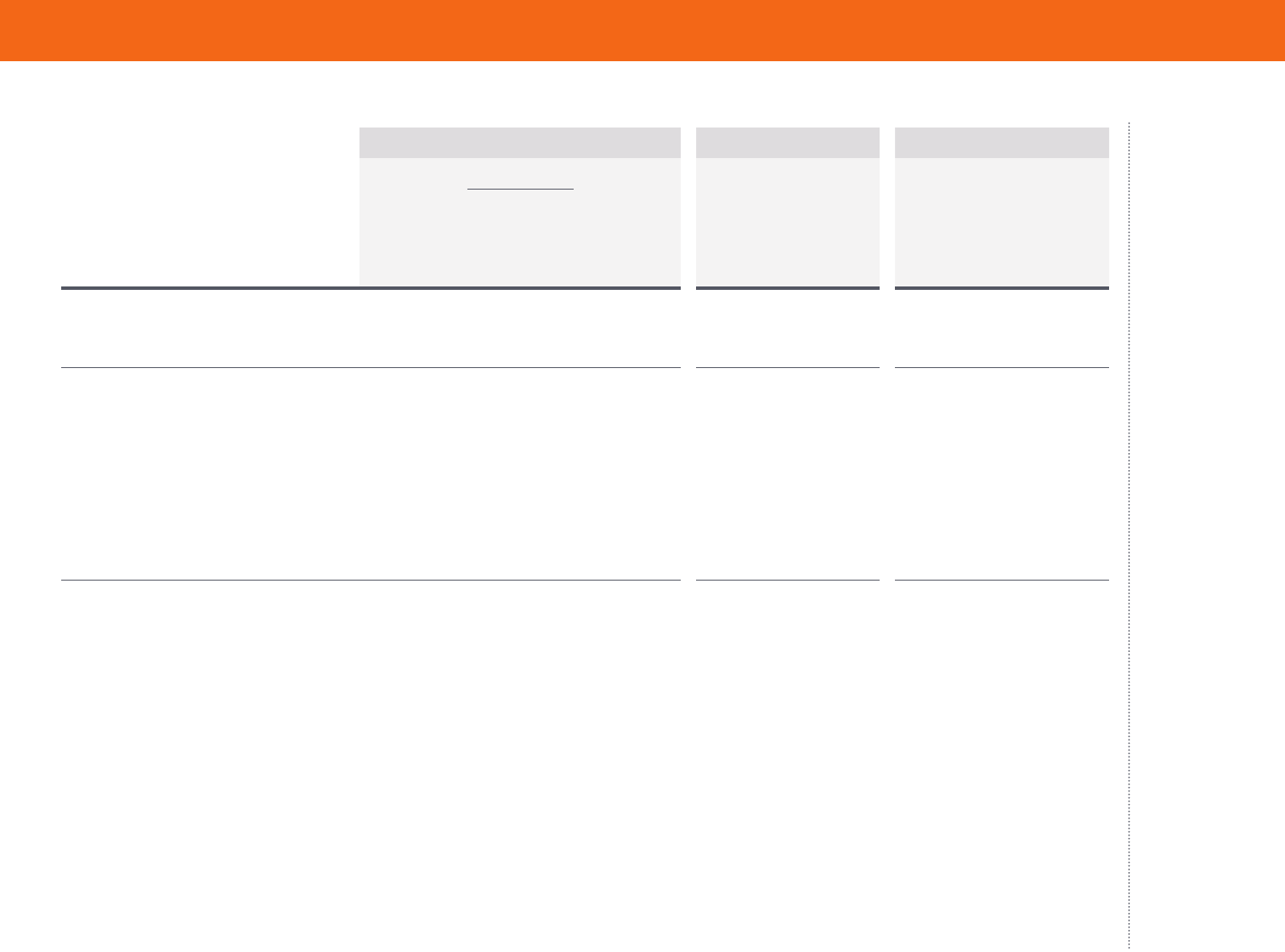

Fewer Adults Report Not Getting Needed Care Because of Costs, but Gains Have

Stalled in Recent Years

It is well documented that

people who gained coverage

under the ACA’s expansions

have better access to health

care as a result.

6

This has

led to overall improvement

in health care access, as

indicated by multiple

surveys.

7

In 2014, the year

the ACA’s major coverage

expansions went into

eect, the share of adults

in our survey who said

that cost prevented them

from getting health care

that they needed, such as

prescription medication,

dropped significantly (Table

4). But there has been no

significant improvement

since then.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Fewer Adults Report Not Getting Needed Care Because of Costs, but Gains Have Stalled in

Recent Years

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

37

37

41

43

36

34

35

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Percent of adults ages 19–64 who reported any of the following

cost-related access problems in the past year:

• Had a medical problem but did not visit doctor or clinic

• Did not fill a prescription

• Skipped recommended test, treatment, or follow-up

• Did not get needed specialist care

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 9

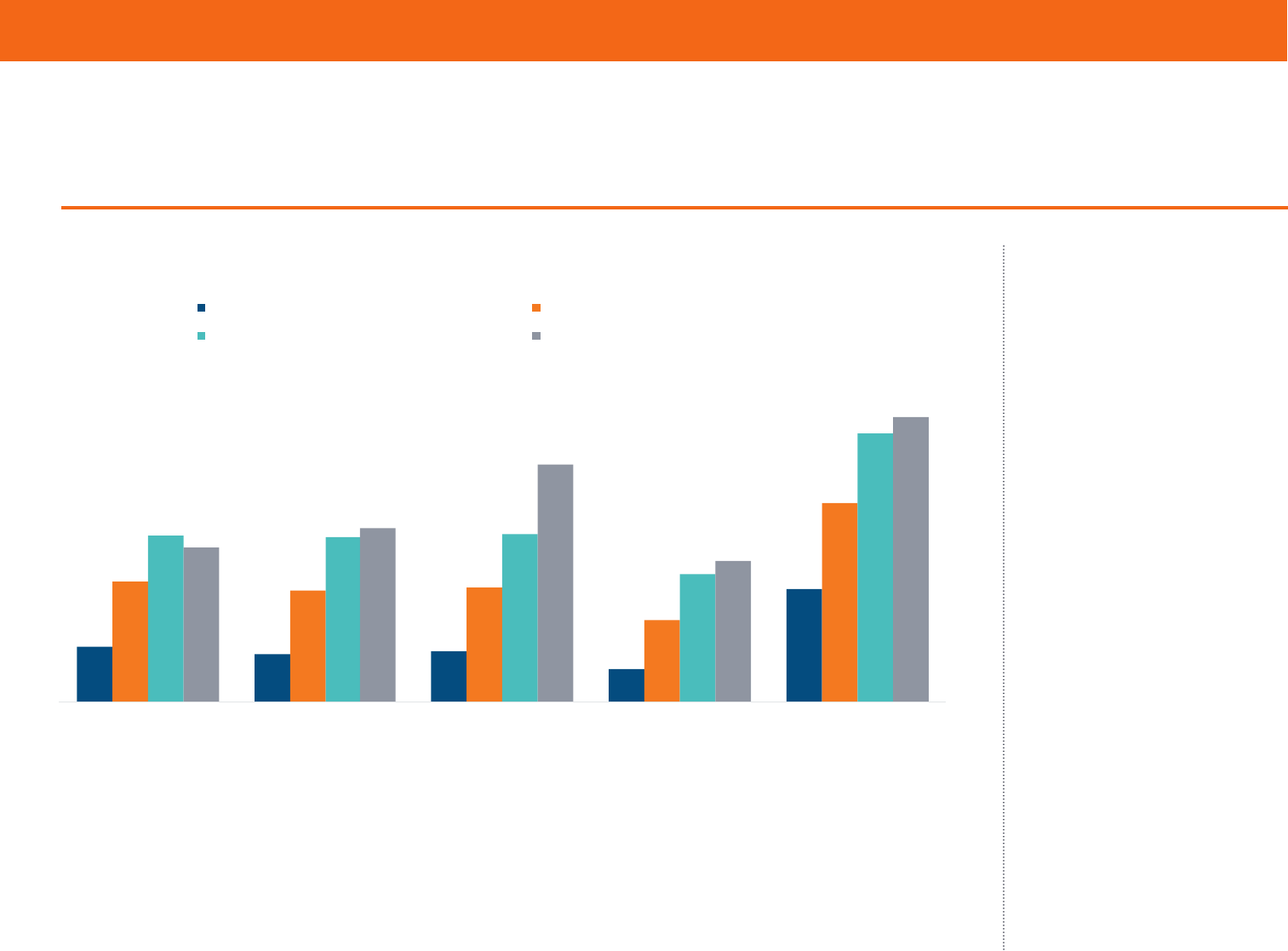

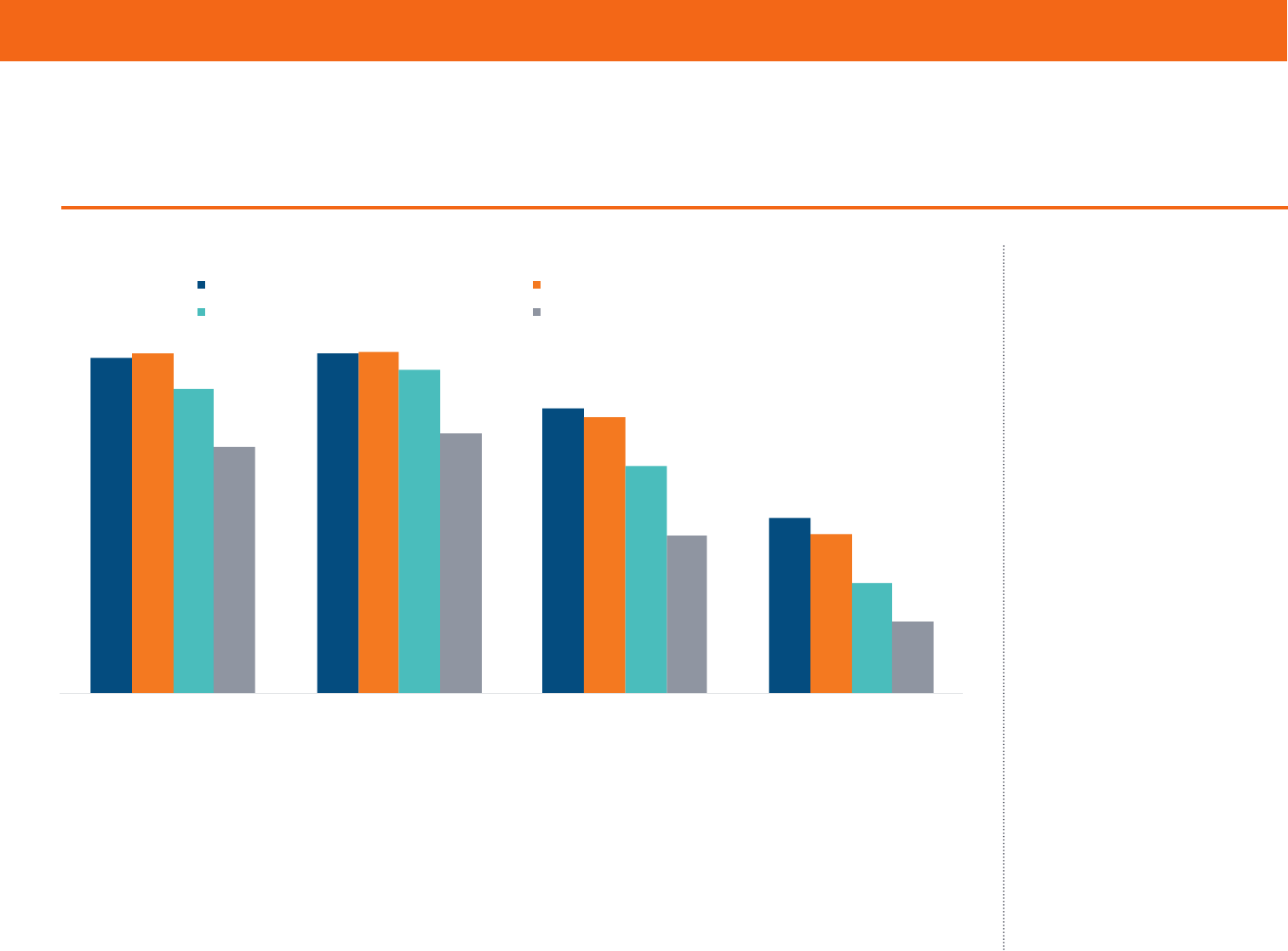

Inadequate Coverage Is Associated with More Cost-Related Problems Getting

Needed Care

The lack of continued

improvement in

overall access to care

nationally reflects the

fact that coverage gains

have plateaued, and

underinsured rates have

climbed. People who

experience any time

uninsured are more likely

than any other group to

delay getting care because

of cost (Table 5). And among

people with coverage

all year, those who were

underinsured reported

cost-related delays in getting

care at nearly double the

rate of those who were not

underinsured.

Notes: * Includes any of the following because of cost: did not ll a prescription; skipped recommended medical test, treatment, or follow-up;

had a medical problem but did not visit doctor or clinic; did not see a specialist when needed. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured

all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured

now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to

the survey eld date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Inadequate Coverage Is Associated with More Cost-Related Problems Getting Needed Care

Notes: * Includes any of the following because of cost: did not fill a prescription; skipped recommended medical test, treatment, or follow-up; had a medical problem but did not visit doctor or clinic;

did not see a specialist when needed. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more

of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage

gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to the survey field date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Percent of adults ages 19–64 who had any of four access problems in past year because of cost*

11

10

11

7

23

25

23

24

17

41

35

34

35

27

56

32

36

49

29

59

Did not fill prescription Skipped recommended

test, treatment, or

follow-up

Had a medical p roblem,

did not visit doctor

or clinic

Did not get needed

specialist care

At least one of four

access problems

because of cost

Insured all year, not underinsured Insured all year, underinsured

Insured now, had a coverage gap Uninsured now

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 10

There was modest but

significant improvement

following the ACA’s

coverage expansions in

the proportion of all U.S.

adults who reported having

diculty paying their

medical bills or said they

were paying o medical debt

over time (Table 4). Federal

surveys have found similar

improvements.

8

However,

those gains have stalled.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Fewer Adults Have Difficulty Paying Their Medical Bills, but the Improvement Has Stalled

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys (2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

34

40

41

35

37

37

2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Percent of adults ages 19–64 who reported any of the following

medical bill or debt problems in the past year:

• Had problems paying or unable to pay medical bills

• Contacted by a collection agency for unpaid medical bills

• Had to change way of life to pay bills

• Medical bills/debt being paid off over time

Fewer Adults Have Difficulty Paying Their Medical Bills, but the Improvement

Has Stalled

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 11

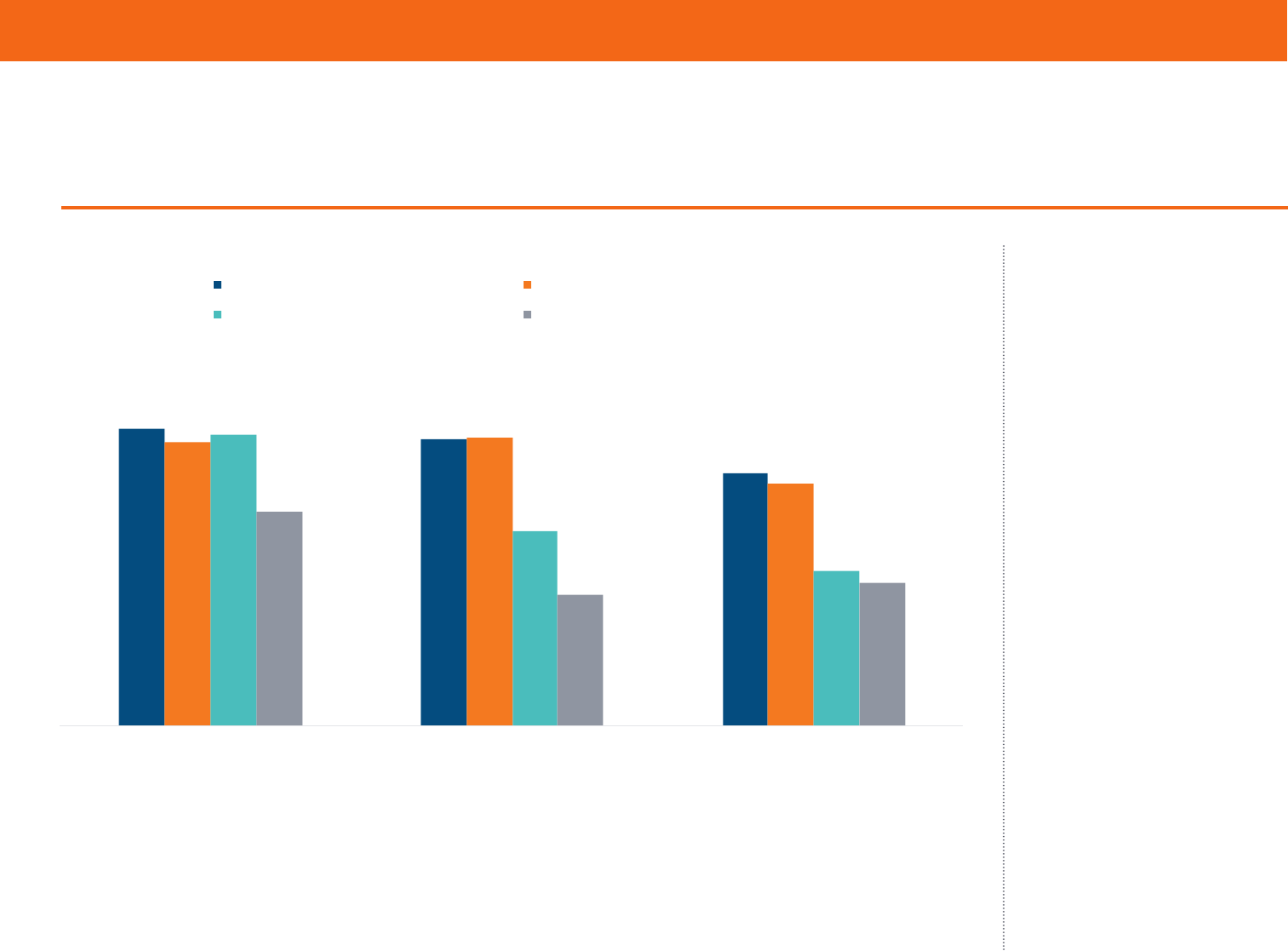

Inadequate insurance

coverage leaves people

exposed to high health care

costs, and these expenses

can quickly turn into

medical debt. More than

half of uninsured adults and

insured adults who have

had a coverage gap reported

that they had had problems

paying medical bills or were

paying o medical debt

over time (Table 6). Among

people who had continuous

insurance coverage, the rate

of medical bill and debt

problems is nearly twice as

high for the underinsured

as it is for people who are

not underinsured.

Notes: * Includes any of the following: had problems paying or unable to pay medical bills; contacted by collection agency for unpaid medical

bills; had to change way of life to pay bills; medical bills/debt being paid over time. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but

experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding

premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a

coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to the survey

eld date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

13

9

6

16

25

30

19 19

33

47

47

29

26

33

56

40

26

22

26

52

Had problems paying

or unable to p ay

medical bills

Contacted by collection

agency for unpaid

medical bills

Had to change

way of life to pay bills

Medical bills/debt

being paid over time

Any bill problem or

medical debt

Insured all year, not underinsured Insured all year, underinsured

Insured now, had a coverage gap Uninsured now

Inadequate Coverage Is Associated with More Problems Paying Medical Bills

Notes: * Includes any of the following: had problems paying or unable to pay medical bills; contacted by collection agency for unpaid medical bills; had to change way of life to pay bills; medical

bills/debt being paid over time. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap”

refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to the survey field date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the survey.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Percent of adults ages 19–64 who had medical bill or debt problems in past year*

Inadequate Coverage Is Associated with More Problems Paying Medical Bills

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 12

Having continuous

coverage makes a significant

dierence in whether

people have a regular

source of care, get timely

preventive care, or receive

recommended cancer

screenings. Adults with

coverage gaps or those who

were uninsured when they

responded to the survey

were the least likely to have

gotten preventive care and

cancer screenings in the

recommended time frame.

Notes: “Continuously insured” refers to adults who were insured for the full year up to and on the survey eld date. “Underinsured” refers

to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled

5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any

point in the 12 months prior to the survey eld date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey.

Respondents were asked if they: had their blood pressure checked within the past two years (in past year if has hypertension or high blood

pressure); had their cholesterol checked in past ve years (in past year if has hypertension, heart disease, or high cholesterol); and had their

seasonal u shot within the past 12 months.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Continuously Insured Adults, Including Those Underinsured, Are More Likely to Get

Preventive Care

Notes: “Continuously insured” refers to adults who were insured for the full year up to and on the survey field date. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to

the survey field date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey. Respondents were asked if they: had their blood pressure checked within the past two

years (in past year if has hypertension or high blood pressure); had their cholesterol checked in past five years (in past year if has hypertension, heart disease, or high cholesterol); and had their

seasonal flu shot within the past 12 months.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

93

94

79

48

94

94

76

44

84

89

63

30

68

72

44

20

Regul ar sou rce

of care

Blood pressure

checked

Cholesterol

checked

Seasonal

flu shot

Insured all year, not underinsured Insured all year, underinsured

Insured now, had a coverage gap Uninsured now

Percent of adults ages 19–64

Continuously Insured Adults, Including Those Underinsured, Are More Likely to Get

Preventive Care

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 13

Being underinsured,

however, does not seem

to reduce the likelihood

of having a usual source

of care or receiving timely

preventive care or cancer

screens — provided a

person has continuous

coverage. This is likely

because the ACA requires

insurers and employers

to cover recommended

preventive care and

cancer screens without

cost-sharing. Even prior

to the ACA, a majority of

employer plans provided

predeductible coverage of

preventive services.

9

Notes: “Continuously insured” refers to adults who were insured for the full year up to and on the survey eld date. “Underinsured” refers

to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty); or deductibles equaled

5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any

point in the 12 months prior to the survey eld date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey.

Respondents were asked if they: received a Pap test within the past three years for females ages 21–64, received a mammogram within the

past two years for females ages 40–64, and received a colon cancer screening within the past ve years for adults ages 50–64.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Source: Sara R. Collins, Herman K. Bhupal, and Michelle M. Doty, Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and

Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured — Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018 (Commonwealth Fund,

Feb. 2019).

Continuously Insured Adults, Including Those Underinsured, Are More Likely to Get

Cancer Screenings

73

71

63

70

71

60

72

48

38

53

32

35

Received Pap test Received mammogram Received colon cancer screening

Insured all year, not underinsured Insured all year, underinsured

Insured now, had a coverage gap Uninsured now

Notes: “Continuously insured” refers to adults who were insured for the full year up to and on the survey field date. “Underinsured” refers to adults who were insured all year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaled 5% or more of income if low-income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5% or more of income. “Insured now, had a coverage gap” refers to adults who were insured at the time of the survey but were uninsured at any point in the 12 months prior to

the survey field date. “Uninsured now” refers to adults who reported being uninsured at the time of the survey. Respondents were asked if they: received a Pap test within the past three years for

females ages 21–64, received a mammogram within the past two years for females ages 40–64, and received a colon cancer screening within the past five years for adults ages 50–64.

Data: Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (2018).

Percent of adults ages 19–64

Continuously Insured Adults, Including Those Underinsured, Are More Likely to

Get Cancer Screenings

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 14

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

U.S. working-age adults are significantly more likely to have health

insurance since the ACA became law in 2010. But the improvement

in uninsured rates has stalled. In addition, more people have health

plans that fail to adequately protect them from health care costs, with

the fastest deterioration in cost protection occurring in the employer

market. The ACA made only minor changes to employer plans, and

the erosion in cost protection has taken a bite out of the progress

made in Americans’ health coverage since the law’s enactment.

Both the federal government and the states, however, have the ability

to extend the law’s coverage gains and improve the cost protection

of both individual-market and employer plans. Here is a short list of

policy options:

Increase Coverage

• Expand Medicaid without restrictions. The 2018 midterm elections

moved as many as five states closer to joining the 32 states that,

along with the District of Columbia, have expanded eligibility

for Medicaid under the ACA.

10

As many as 300,000 people

may ultimately gain coverage as a result.

11

But, encouraged by

the Trump administration, several states are imposing work

requirements on people eligible for Medicaid — a move that

could reverse these coverage gains. So far, the U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services (HHS) has approved similar

work-requirement waivers in seven states and is considering

applications from at least seven more. Arkansas imposed a work

requirement last June, and, to date, more than 18,000 adults have

lost their insurance coverage as a result.

• Ban or place limits on short-term health plans and other insurance

that doesn’t comply with the ACA. The Trump administration

loosened regulations on short-term plans that don’t comply with

the ACA, potentially leaving people who enroll in them exposed

to high costs and insurance fraud. These plans also will draw

healthier people out of the marketplaces, increasing premiums

for those who remain and federal costs of premium subsidies.

Twenty-three states have banned or placed limits on short-term

insurance policies. Some lawmakers have proposed a federal ban.

• Reinsurance, either state or federal. The ACA’s reinsurance

program was eective in lowering marketplace premiums. Aer it

expired in 2017, several states implemented their own reinsurance

programs.

12

Alaska’s program reduced premiums by 20 percent in

2018. These lower costs particularly help people whose incomes

are too high to qualify for ACA premium tax credits. More states

are seeking federal approval to run programs in their states. Several

congressional bills have proposed a federal reinsurance program.

• Reinstate outreach and navigator funding for the 2020 open-

enrollment period. The administration has nearly eliminated

funding for advertising and assistance to help people enroll in

marketplace plans.

13

Research has found that both activities

are eective in increasing enrollment.

14

Some lawmakers have

proposed reinstating this funding.

• Li the 400-percent-of-poverty cap on eligibility for marketplace

tax credits. This action would help people with income exceeding

$100,000 (for a family of four) better aord marketplace plans. The

tax credits work by capping the amount people pay toward their

premiums at 9.86 percent. Liing the cap has a built in phase out:

as income rises, fewer people qualify, since premiums consume an

increasingly smaller share of incomes. RAND researchers estimate

that this policy change would increase enrollment by 2 million

and lower marketplace premiums by as much as 4 percent as

healthier people enroll. It would cost the federal government an

estimated $10 billion annually.

15

Legislation has been introduced

to li the cap.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 15

• Make premium contributions for individual market plans fully tax

deductible. People who are self-employed are already allowed to

do this.

16

• Fix the so-called family coverage glitch. People with employer

premium expenses that exceed 9.86 percent of their income

are eligible for marketplace subsidies, which trigger a federal

tax penalty for their employers. There’s a catch: this provision

applies only to single-person policies, leaving many middle-

income families caught in the “family coverage glitch.” Congress

could lower many families’ premiums by pegging unaordable

coverage in employer plans to family policies instead of single

policies.

17

Reduce Coverage Gaps

• Inform the public about their options. People who lose coverage

during the year are eligible for special enrollment periods for

ACA marketplace coverage. Those eligible for Medicaid can sign

up at any time. But research indicates that many people who

lose employer coverage do not use these options.

18

The federal

government, the states, and employers could increase awareness

of insurance options outside the open-enrollment periods

through advertising and education.

• Reduce churn in Medicaid. Research shows that over a two-year

period, one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries leave the program

and become uninsured.

19

Many do so because of administrative

barriers.

20

By imposing work requirements, as some states are

doing, this involuntary disenrollment is likely to get worse. To

help people stay continuously covered, the federal government

and the states could consider simplifying and streamlining the

enrollment and reenrollment processes.

• Extend the marketplace open-enrollment period. The current

open-enrollment period lasts just 45 days. Six states that run

their own marketplaces have longer periods, some by as much

as an additional 45 days. Other states, as well as the federal

marketplace, could extend their enrollment periods as well.

Improve Individual-Market Plans’ Cost Protections

• Fund and extend the cost-sharing reduction subsidies. The Trump

administration eliminated payments to insurers for oering

plans with lower deductibles and copayments. Insurers, which

by law must still oer reduced-cost plans, are making up the

lost revenue by raising premiums. But this fix, while benefiting

enrollees who are eligible for premium tax credits, has distorted

both insurer pricing and consumer choice.

21

In addition, it is

unknown whether the administration’s support for the fix

will continue in the future, creating uncertainty for insurers.

22

Congress could reinstate the payments to insurers and consider

making the plans available to people with higher earnings.

• Increase the number of services excluded from the deductible.

Most plans sold in the individual market exclude certain

services from the deductible, such as primary care visits and

certain prescriptions.

23

As the survey data suggest, these types

of exclusions appear to be important in ensuring access to

preventive care among people who have coverage but are

underinsured. In 2016, HHS provided a standardized plan

option for insurers that excluded eight health services —

including mental health and substance-use disorder outpatient

visits and most prescription drugs — from the deductible at the

silver and gold level.

24

The Trump administration eliminated

the option in 2018. Congress could make these exceptions

mandatory for all plans.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 16

Improve Employer Plans’ Cost Protections

• Increase the ACA’s minimum level of coverage. Under the ACA,

people in employer plans may become eligible for marketplace

tax credits if the actuarial value of their plan is less than 60

percent, meaning that under 60 percent of health care costs,

on average, are covered. Congress could increase this to the 70

percent standard of silver-level marketplace plans, or even higher.

• Require deductible exclusions. Congress could require employers

to increase the number of services that are covered before someone

meets their deductible. Most employer plans exclude at least

some services from their deductibles.

25

Congress could specify a

minimum set of exclusions for employer plans that might resemble

the standardized-choice options that once existed for ACA plans.

• Refundable tax credits for high out-of-pocket costs. Congress could

make refundable tax credits available to help insured Americans

pay for qualifying out-of-pocket costs that exceed a certain

percentage of their income.

26

• Protect consumers from surprise medical bills. Several states

have passed laws that protect patients and their families from

unexpected medical bills, generally from out-of-network

providers.

27

A bipartisan group of U.S. senators has proposed

federal legislation to protect consumers, including people

enrolled in employer and individual-market plans.

Health care costs are primarily what’s driving growth in premiums

across all health insurance markets. Employers and insurers

have kept premiums down by increasing consumers’ deductibles

and other cost-sharing, which in turn is making more people

underinsured. This means that policy options like the ones we’ve

highlighted above will need to be paired with eorts to slow medical

spending. These could include changing how health care is organized

and providers are paid to achieve greater value for health care dollars

and better health outcomes.

28

The government also could tackle

rising prescription drug costs

29

and use antitrust laws to combat the

growing concentration of insurer and provider markets.

30

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 17

HOW WE CONDUCTED THIS STUDY

The Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2018, was

conducted by SSRS from June 27 to November 11, 2018. The survey

consisted of telephone interviews in English and Spanish and was conducted

among a random, nationally representative sample of 4,225 adults ages 19

to 64 living in the continental United States. A combination of landline and

cellular phone random-digit dial samples was used to reach people. In all, 725

interviews were conducted with respondents on landline telephones and

3,500 interviews were conducted on cellular phones.

The sample was designed to generalize to the U.S. adult population and to

allow separate analyses of responses of low-income households. Statistical

results are weighted to correct for the stratified sample design, the

overlapping landline and cellular phone sample frames, and disproportionate

nonresponse that might bias results. The data are weighted to the U.S. adult

population by age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, household size, geographic

region, population density, and household telephone use, using the U.S.

Census Bureau’s 2017 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

The resulting weighted sample is representative of the approximately 193.9

million U.S. adults ages 19 to 64. The survey has an overall margin of sampling

error of +/– 1.9 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level. The

RDD landline portion of the survey achieved a 8.4 percent response rate and

the RDD cellular phone component achieved a 5.2 percent response rate.

We also report estimates from the 2001, 2003, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2014, and

2016 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys. These surveys

were conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International

using the same stratified sampling strategy that was used in 2018, except the

2001, 2003, and 2005 surveys did not include a cellular phone random-digit

dial sample. In 2001, the survey was conducted from April 27 through July

29, 2001, and included 2,829 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2003, the survey was

conducted from September 3, 2003, through January 4, 2004, and included

3,293 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2005, the survey was conducted from August

18, 2005, to January 5, 2006, among 3,352 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2010, the

survey was conducted from July 14 to November 30, 2010, among 3,033

adults ages 19 to 64; in 2012, the survey was conducted from April 26 to

August 19, 2012, among 3,393 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2014, the survey was

conducted from July 22 to December 14, 2014, among 4,251 adults ages 19

to 64; and in 2016, the survey was conducted from July 12 to November 20,

2016, among 4,186 adults ages 19 to 64.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 18

CHANGES IN U.S. UNINSURED RATES SINCE 2013

Uninsured Rate for Adults Compared to Other Surveys Since 2013

Survey

Preimplementation uninsured rate (%)

[95% CI]

Lowest uninsured rate (%)

[95% CI]

Current uninsured rate (%)

[95% CI]

Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey

a

19.3% [17.5%–21.3%] 12.0% [10.7%–13.52%] (July–Nov. 2016) 12.4% [11.2%–13.7%]

Commonwealth Fund Aordable Care Act Tracking Survey

b

19.9% [18.5%–21.4%] 12.7% [11.5%–14.0%] (Feb.–Apr. 2016) 15.5% [13.7%–17.5%]

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (2016)

c

20.4% [19.7%–21.1.%] 12.4% [11.7%–13.1%] (2016) 12.5% [11.6%–13.4%]

Current Population Survey (CPS)

d

18.3% 11.9% (2016) 12.1%

Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index

e,f

20.8% 13.1% (Q4 2016) 16.3%

Urban Institute Health Reform Monitoring Survey

g

17.4% 9.8% (Q1 2016) 10.8%

Methodological Differences Between Surveys

Survey Population Time Frame Sample Frame Response Rate

Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health

Insurance Survey

U.S. adults ages 19–64 Apr.–Aug. 2012 to June–Nov. 2018 Dual-frame, RDD telephone survey

2012: 22% landline, 19% cell;

2018: 8.4% landline, 5.2% cell

Commonwealth Fund Aordable Care

Act Tracking Survey

U.S. adults ages 19–64 July–Sept. 2013 to Feb.–Mar. 2018 Dual-frame, RDD telephone survey

2013: 20.1%;

2018: 7.5%

National Health Interview Survey

(NHIS) (2016)

h,i

U.S. adults ages 18–64 2013 to Jan.–June 2018 Multistage area probability design 70%

Current Population Survey (CPS)

d

U.S. adults ages 18–64 Mar. 2013–2017

Probability-selected sample; personal and

telephone interviews

j

2018: 85%

k

;

2014: 79.6%

l

Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index

m

U.S. adults ages 18–64 2013 to Oct.–Dec. 2018

Before 2018: dual-frame RDD telephone survey;

2018: address-based sampling frame with web

survey

Urban Institute Health Reform

Monitoring Survey

n

U.S. adults ages 18–64 July–Sept. 2013 to Jan.–Mar. 2018

KnowledgePanel-probability-based internet

panel of 55,000 households

~5%

a

Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, Apr.–Aug. 2012, July–Nov. 2016, June–Nov. 2018.

b

Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey, July–Sept. 2013, Feb.–Apr. 2016, Feb.–Mar. 2018.

c

Emily P. Zammitti, Robin A. Cohen, and Michael E. Martinez, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, Jan.–June 2017 (National Center for Health Statistics, Nov. 2017);

and Michael E. Martinez, Emily P. Zammitti, and Robin A. Cohen, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, Jan.–June 2018 (National Center for Health Statistics, Nov. 2018).

d

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013, 2016, and 2017 Current Population Reports; for 2013, see https://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html.

e

Stephanie Marken, “U.S. Uninsured Rate at 11.4% in Second Quarter,” Gallup News, July 10, 2015.

f

Dan Witters, “U.S. Uninsured Rate Rises to Four-Year High,” Gallup News, Jan. 23, 2019.

g

Jennifer Haley et al., “Adults’ Uninsurance Rates Increased by 2018, Especially in States That Did Not Expand Medicaid — Leaving Gaps in Coverage, Access, and Affordability,” Health Affairs Blog, Sept. 26, 2018.

h

Martinez, Zammitti, and Cohen, Health Insurance Coverage, 2018.

i

National Center for Health Statistics, “About the National Health Interview Survey,” fact sheet (NCHS, last updated Jan. 19, 2019).

j

U.S. Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey (CPS): Methodology,” Census Bureau, n.d.

k

U.S. Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey (CPS): Non-Response Rates,” Census Bureau, n.d.

l

U.S. Census Bureau, “Current Population Survey, 2014 ASEC Technical Documentation,” Census Bureau, 2014.

m

Gallup, “How Does the Gallup National Health and Well-Being Index Work?,” Gallup, n.d.

n

Urban Institute Health Policy Center, “Health Reform Monitoring Survey: HRMS Frequently Asked Questions,” Urban, n.d.

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 19

Table 1. Insurance Status by Demographics, 2018 (base: adults ages 19–64)

Total

(19–64)

Insured

all year

Insured all year,

not underinsured

Insured all year,

underinsured

Insured now, had

a coverage gap

Uninsured

now

Total (millions) 193.9 150.6 106.8 43.8 19.3 24.0

Percent distribution 100.0% 77.7% 55.1% 22.6% 10.0% 12.4%

Unweighted n 4225 3254 2272 982 416 555

Gender

Female 52 78 56 22 11 11

Male 48 77 54 23 9 14

Age

19–34 32 69 48 21 14 17

35–49 30 79 58 21 9 12

50–64 35 84 59 26 7 8

Race/Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic White 59 83 58 25 8 9

Black 12 73 56 18 16 11

Latino 18 62 45 17 14 24

Asian/Pacic Islander 4 81 61 21 8 10

Other/Mixed 5 77 51 26 9 14

Poverty status

Below 133% poverty 25 68 37 31 14 18

133%–249% poverty 19 69 45 24 14 17

250%–399% poverty 19 80 57 23 10 10

400% poverty or more 29 91 75 16 5 3

Below 200% poverty 39 67 39 28 15 18

200% poverty or more 53 86 67 19 7 7

Fair/Poor health status,

or any chronic condition*

50 78 54 24 10 12

Adult work status

Full-time 53 81 59 22 9 10

Part-time 14 67 47 20 16 17

Not currently employed 33 77 52 25 9 14

Employer size**

1–19 employees 23 66 44 21 10 24

20–49 employees 11 79 59 20 9 13

50–99 employees 8 74 57 17 14 13

100 or more employees 56 85 62 22 10 6

NOTES

“Underinsured” refers to

adults who were insured all

year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket

costs, excluding premiums,

equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled

5% or more of income if low-

income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5%

or more of income. “Insured

now, had a coverage gap”

refers to adults who were

insured at the time of the

survey but were uninsured at

any point in the 12 months

prior to the survey eld date.

“Uninsured now” refers to

adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the

survey.

* At least one of the

following chronic conditions:

hypertension or high

blood pressure; heart

disease; diabetes; asthma,

emphysema, or lung disease;

or high cholesterol.

** Base: Full- and part-time

employed adults ages 19–64.

DATA

Commonwealth Fund

Biennial Health Insurance

Survey (2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 20

Table 2. Insurance Status, 2003–2018 (base: adults ages 19–64)

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Total (millions) 172.0 172.5 183.6 183.9 182.8 187.4 193.9

Percent distribution 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100%

Unweighted n 3293 3352 3033 3393 4251 4186 4225

Insured all year 74 72 72 70 72 78 78

Insured all year, not underinsured 65 63 56 54 55 56 55

Insured all year, underinsured 9 9 16 16 17 22 23

Insured now, had a coverage gap 9 9 8 10 13 10 10

Uninsured now 17 18 20 19 16 12 12

NOTES

“Underinsured” refers to

adults who were insured all

year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket

costs, excluding premiums,

equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled

5% or more of income if low-

income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5%

or more of income. “Insured

now, had a coverage gap”

refers to adults who were

insured at the time of the

survey but were uninsured at

any point in the 12 months

prior to the survey eld date.

“Uninsured now” refers to

adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the

survey.

DATA

Commonwealth Fund Biennial

Health Insurance Surveys

(2003, 2005, 2010, 2012,

2014, 2016, 2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 21

Table 3. Uninsured Rate by Demographics, 2003–2018 (base: adults ages 19–64)

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Total (millions uninsured) 29.8 31.6 37.1 35.5 28.7 22.6 24.0

Percent distribution 17% 18% 20% 19% 16% 12% 12%

Unweighted n 643 716 590 650 685 520 555

Gender

Female 17 18 20 17 13 11 11

Male 17 18 20 22 19 13 14

Age

19–34 24 26 27 23 19 15 17

35–49 15 19 20 22 17 14 12

50–64 11 10 13 13 11 8 8

Race/Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic White 13 13 15 14 10 7 9

Black 23 19 24 20 18 12 11

Latino 37 48 39 40 34 28 24

Asian/Pacic Islander 14 9 9 8 7 4 10

Other/Mixed 17 18 29 29 22 16 14

Poverty status

Below 133% poverty — — 38 35 26 21 18

133%–249% poverty — — 26 22 19 14 17

250%–399% poverty — — 8 11 11 6 10

400% poverty or more — — 4 5 3 3 3

Below 200% poverty 34 39 36 32 24 19 18

200% poverty or more 7 9 7 9 7 4 7

Fair/Poor health status, or

any chronic condition*

17 22 22 20 15 13 12

Adult work status

Full-time 11 14 12 12 11 9 10

Part-time 26 22 32 26 23 16 17

Not currently employed 26 27 28 27 19 15 14

Employer size**

1–19 employees 28 27 — 25 28 24 24

20–49 employees 17 26 — 30 22 14 13

50–99 employees 14 19 13 12 15 12 13

100 or more employees 7 6 8 9 5 4 6

NOTES

“Uninsured” refers to

adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the

survey.

— Data not collected or

collected dierently for that

year.

** Base: Full- and part-time

employed adults ages 19–64.

DATA

Commonwealth Fund Biennial

Health Insurance Surveys

(2003, 2005, 2010, 2012,

2014, 2016, 2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 22

Table 4. Cost-Related Access Problems and Medical Bill Problems by Year (base: adults ages 19–64)

Percent Estimated millions

2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2003 2005 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Total (adults ages 19–64)

100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 172.0 172.5 183.6 183.9 182.8 187.4 189.7

Access problems in past year

Went without needed care in past year

because of cost:

Did not ll prescription 23 25 26 27 19 19 19 39 43 48 50 35 36 37

Skipped recommended test,

treatment, or follow-up

19 20 25 27 19 18 19 32 34 47 49 35 34 36

Had a medical problem, did not visit

doctor or clinic

22 24 26 29 23 20 21 38 41 49 53 42 37 40

Did not get needed specialist care 13 17 18 20 13 13 14 22 30 34 37 23 25 27

At least one of four access problems

because of cost

37 37 41 43 36 34 35 63 64 75 80 66 63 68

Delayed or did not get dental care 27 — 38 39 32 31 33 46 — 69 72 58 57 65

Medical bill problems in past year

Had problems paying or unable to pay

medical bills

23 23 29 30 23 23 24 40 39 53 55 43 43 46

Contacted by collection agency 21 21 23 22 20 21 22 35 36 42 41 37 38 42

Contacted by collection agency for

unpaid medical bills

— 13 16 18 15 14 15 — 22 30 32 27 25 30

Contacted by collection agency

because of billing mistake

— 7 5 4 4 5 5 — 11 9 7 8 9 10

Had to change way of life to pay bills 15 14 17 16 14 14 13 26 24 31 29 26 26 26

Any bill problem* — 28 34 34 29 29 29 — 48 62 63 53 53 57

Medical bills/debt being paid o over

time

— 21 24 26 22 24 23 — 37 44 48 40 46 45

Any bill problem or medical debt* — 34 40 41 35 37 37 — 58 73 75 64 70 71

NOTES

— Data not collected for

that year.

* Does not include adults who

reported being contacted by

a collection agency because

of a billing mistake..

DATA

Commonwealth Fund Biennial

Health Insurance Surveys

(2003, 2005, 2010, 2012,

2014, 2016, 2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 23

Table 5. Cost-Related Access Problems and Preventive Care by Insurance Continuity, Insurance Status, and Poverty

(base: adults ages 19–64)

Insurance status Insurance type** Federal poverty level

Total 19–64

Insured all year

Insured all year

Insured now,

had a coverage gap

Uninsured now

Employer

Individual*

Medicaid

Medicare (under

age 65, disabled)

Below 133%

poverty

133%– 249%

poverty

250%– 399%

poverty

400% poverty

or more

Insured all

year, not

underinsured

Insured

all year,

underinsured

Total (millions) 193.9 150.6 106.8 43.8 19.3 24.0 102.6 15.8 22.5 15.8 47.8 37.5 37.4 57.1

Percent distribution 100% 78% 55% 23% 10% 12% 53% 8% 12% 8% 25% 19% 19% 29%

Unweighted n 4225 3254 2272 982 416 555 2016 360 523 479 1212 796 783 1138

Access problems in past year

Went without needed care in past year because of cost:

Did not ll prescription 19 15 11 25 35 32 16 21 22 20 24 22 19 13

Skipped recommended test,

treatment, or follow-up

19 14 10 23 34 36 16 25 14 14 18 25 20 14

Had a medical problem,

did not visit doctor or clinic

21 15 11 24 35 49 16 24 16 14 24 28 23 13

Did not get needed specialist care 14 10 7 17 27 29 11 17 12 12 16 19 15 8

At least one of four access

problems because of cost

35 29 23 41 56 59 31 42 32 32 39 43 38 26

Delayed or did not get dental care 33 28 23 41 49 56 26 38 38 35 39 45 38 21

Preventive care

Regular source of care 89 93 93 94 84 68 92 86 93 96 88 88 88 93

Blood pressure checked in past two years

¥

91 94 94 94 89 72 94 94 89 96 88 89 90 96

Dental exam in past year 60 67 67 67 40 32 72 59 49 40 43 49 61 79

Received mammogram in past two years

(females age 40+)

65 71 71 71 48 32 75 60 55 64 56 48 70 75

Received Pap test in past three years

(females ages 21–64)

70 72 73 70 72 53 77 64 71 58 67 63 72 78

Received colon cancer screening in

past ve years (age 50+)

58 62 63 60 38 35 62 52 51 63 50 51 64 63

Cholesterol checked in past ve years

¥¥

72 78 79 76 63 44 80 70 69 77 63 63 71 87

Seasonal u shot in past year 42 47 48 44 30 20 48 36 39 55 40 36 38 51

Access problems for people with health conditions

Unweighted n 474 276 118 158 ^^ 115 143 ^^ ^^ ^^ 198 125 ^^ ^^

Skipped doses or did not ll a prescription

for medications for the health condition(s)

because of the cost of the medicines^

19 14 10 23 ^^ 45 14 ^^ ^^ ^^ 22 30 ^^ ^^

NOTES

“Underinsured” refers to

adults who were insured all

year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket

costs, excluding premiums,

equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled

5% or more of income if low-

income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5% or

more of income. “Insured now,

had a coverage gap” refers to

adults who were insured at the

time of the survey but were

uninsured at any point in the

12 months prior to the survey

eld date. “Uninsured now”

refers to adults who reported

being uninsured at the time of

the survey.

* Individual includes adults

who are enrolled in either

marketplace plans or

purchased directly o the

marketplace.

** Insurance type at time of

survey.

¥ In past year if respondent

has hypertension or high

blood pressure.

¥¥ In past year if respondent

has hypertension or high

blood pressure, heart disease,

or high cholesterol.

^ Base: Respondents with

at least one of the following

health problems: hypertension

or high blood pressure, heart

disease, diabetes, asthma,

emphysema, lung disease, high

cholesterol, depression, kidney

disease, cancer, or stroke.

^^ Insucient sample.

DATA

Commonwealth Fund

Biennial Health Insurance

Survey (2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 24

Table 6. Medical Bill Problems, by Insurance Continuity, Insurance Status, and Poverty (base: adults ages 19–64)

Insurance status Insurance type** Federal poverty level

Total 19–64

Insured all year

Insured all year

Insured now,

had a coverage gap

Uninsured now

Employer

Individual*

Medicaid

Medicare (under

age 65, disabled)

Below 133%

poverty

133%– 249%

poverty

250%– 399%

poverty

400% poverty

or more

Insured all

year, not

underinsured

Insured

all year,

underinsured

Total (millions) 193.9 150.6 106.8 43.8 19.3 24.0 102.6 15.8 22.5 15.8 47.8 37.5 37.4 57.1

Percent distribution 100% 78% 55% 23% 10% 12% 53% 8% 12% 8% 25% 19% 19% 29%

Unweighted n 4225 3254 2272 982 416 555 2016 360 523 479 1212 796 783 1138

Medical bill problems in past year

Went without needed care in past year because of cost:

Had problems paying or unable to pay

medical bills

24 18 13 30 47 40 19 28 23 35 28 35 28 12

Contacted by collection agency for unpaid

medical bills

15 12 9 19 29 26 12 14 15 29 21 27 14 5

Had to change way of life to pay bills 13 10 6 19 26 22 10 16 11 25 16 20 14 7

Any bill problem 29 24 18 38 52 47 23 35 30 46 36 43 32 14

Medical bills/debt being paid o over time 23 21 16 33 33 26 24 22 19 28 21 30 27 19

Any bill problem or medical debt 37 32 25 47 56 52 32 42 35 53 42 48 40 24

Base: Any medical debt

How much are the medical bills that are

being paid o over time?

Less than $2,000 43 46 51 40 35 36 46 52 36 35 46 40 46 39

$2,000 to less than $4,000 22 23 21 26 18 17 22 24 27 15 20 20 22 27

$4,000 to less than $8,000 17 14 9 21 23 22 18 8 9 18 10 21 16 22

$8,000 to less than $10,000 4 4 3 4 5 7 2 6 9 4 6 5 4 3

$10,000 or more 12 10 11 8 16 18 10 6 17 14 14 11 13 9

Was this for care received in past year or earlier?

Past year 47 50 53 48 38 35 53 54 34 37 38 41 49 57

Earlier year 46 43 42 43 49 58 39 38 63 55 56 51 39 38

Both 7 6 5 9 11 7 8 5 1 8 5 8 11 5

Were these bills for someone who was insured

at the time the care was provided or was the

person uninsured then?

Insured at time care was provided 65 77 77 79 42 30 81 73 45 63 49 55 74 86

Uninsured at time care was provided 28 16 15 17 46 64 13 19 47 29 43 37 21 7

NOTES

“Underinsured” refers to

adults who were insured all

year but experienced one of

the following: out-of-pocket

costs, excluding premiums,

equaled 10% or more of

income; out-of-pocket costs,

excluding premiums, equaled

5% or more of income if low-

income (<200% of poverty);

or deductibles equaled 5%

or more of income. “Insured

now, had a coverage gap”

refers to adults who were

insured at the time of the

survey but were uninsured at

any point in the 12 months

prior to the survey eld date.

“Uninsured now” refers to

adults who reported being

uninsured at the time of the

survey.

* Individual includes adults

who are enrolled in either

marketplace plans or

purchased directly o the

marketplace.

** Insurance type at time of

survey.

DATA

Commonwealth Fund

Biennial Health Insurance

Survey (2018).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 25

NOTES

1. Analysis of the 2018 U.S. Current Population Survey by Ougni Chakraborty

and Sherry Glied of New York University for the Commonwealth Fund.

2. One of the ACA’s most notable provisions aimed at employers was the

so-called employer mandate — the requirement that large firms oer aordable

coverage to full-time employees or pay penalties.

3. Princeton Survey Research Associates International conducted the prior-year

Biennial Surveys analyzed in this brief.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Eectuated Enrollment for the

First Half of 2018,” fact sheet, Nov. 28, 2018.

5. Sara R. Collins and David C. Radley, The Cost of Employer Insurance Is a

Growing Burden for Middle-Income Families (Commonwealth Fund, Dec. 2018).

6. Benjamin D. Sommers et al.,“Three-Year Impacts of the Aordable Care Act:

Improved Medical Care and Health Among Low-Income Adults,” Health Aairs

Web First, published online May 17, 2017; and Munira Z. Gunja, Sara R. Collins,

and Herman K. Bhupal, Is the Aordable Care Act Helping Consumers Get Health

Care? Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Aordable Care Act Tracking

Survey, March–June 2017 (Commonwealth Fund, Dec. 2017).

7. Tainya C. Clarke, Tina Norris, and Jeannine S. Schiller, Early Release of Selected

Estimates Based on Data From the 2016 National Health Interview Survey

(National Center for Health Statistics, May 2017).

8. Robin A. Cohen and Jeannine S. Schiller, Problems Paying Medical Bills Among

Persons Under Age 65: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health

Interview Survey, 2011–June 2016 (National Center for Health Statistics, Dec.

2015).

9. “Interim Final Rules for Group Health Plans and Health Insurance Issuers

Relating to Coverage of Preventive Services Under the Patient Protection and

Aordable Care Act,” Federal Register 75, no. 137 (July 19, 2010): 41726–60.

10. In three states — Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah — voters approved ballot

initiatives to expand eligibility for Medicaid; Kansas elected a Democratic

governor who has pledged to expand; Maine’s newly elected Democratic

governor is expanding Medicaid one year aer voters approved a ballot initiative

to expand. See Donald Moulds et al., “The Midterm Election Results Have Big

Implications for Health Care,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, Nov. 7.

2018.

11. Matthew Buettgens, The Implications of Medicaid Expansion in the Remaining

States: 2018 Update (Urban Institute, May 2018); and Rachel Garfield, Anthony

Damico, and Kendal Orgera, The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States

that Do Not Expand Medicaid (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2018).

12. American Academy of Actuaries, Drivers of 2016 Health Insurance Premium

Changes (AAA, Aug. 2015).

13. Sara R. Collins, “Consumers Shopping for Health Plans Are Le in the Dark by

Trump Administration,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, July 19, 2018.

14. Sara R. Collins, Munira Z. Gunja, and Michelle M. Doty, Following the ACA

Repeal-and-Replace Eort, Where Does the U.S. Stand on Insurance Coverage?

Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Aordable Care Act Tracking Survey,

March–June 2017 (Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2017).

15. Jodi Liu and Christine Eibner, Expanding Enrollment Without the

Individual Mandate: Options to Bring More People into the Individual Market

(Commonwealth Fund, Aug. 2018).

16. Timothy S. Jost, “Fixing Our Most Pressing Health Insurance Problems: A

Bipartisan Path Forward,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, July 13,

2017.

17. Christine Eibner, Sarah Nowak, and Jodi Liu, Hillary Clinton’s Health Care Re-

form Proposals: Anticipated Eects on Insurance Coverage, Out-of-Pocket Costs,

and the Federal Deficit (Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2016).

commonwealthfund.org Survey Brief, February 2019

Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured 26

18. Matthew Buettgens, Stan Dorn, and Hannah Recht, More Than 10 Million

Uninsured Could Obtain Marketplace Coverage Through Special Enrollment

Periods (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute, Nov. 2015).

19. Sara R. Collins, Sherry A. Glied, and Adlan Jackson, The Potential Implications

of Work Requirements for the Insurance Coverage of Medicaid Beneficiaries: The

Case of Kentucky (Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2018).

20. Benjamin D. Sommers, “Loss of Health Insurance Among Non-Elderly Adults

in Medicaid,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 24, no. 1 (Jan. 2009): 1–7.

21. Christina Cousart, How Elimination of Cost-Sharing Reduction Payments

Changed Consumer Enrollment in State-Based Marketplaces (National Academy

for State Health Policy, March 20, 2018).

22. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “CMS Issues the Proposed

Payment Notice for the 2020 Coverage Year,” news release, Jan. 17, 2019.

23. Munira Z. Gunja, Sara R. Collins, and Sophie Beutel, How Deductible

Exclusions in Marketplace Plans Improve Access to Many Health Care Services

(Commonwealth Fund, Mar. 2016).

24. Sara R. Collins, “The Trump Administration’s New Marketplace Rules:

Regulatory Simplification or More Complexity for Consumers?” To the Point

(blog), Commonwealth Fund, Apr. 13, 2018.

25. Jon R. Gabel et al., Consumer Cost-Sharing in Marketplace vs. Employer Health

Insurance Plans, 2015 (Commonwealth Fund, Dec. 2015).

26. Christine Eibner, Sarah Nowak, and Jodi Liu, Hillary Clinton’s Health Care

Reform Proposals: Anticipated Eects on Insurance Coverage, Out-of-Pocket

Costs, and the Federal Deficit (Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2016).