Key Takeaways:

• People experiencing homelessness are unemployed or underemployed at

disproportionately high rates, but many want to work.

• Individual barriers to employment include mental and physical health challenges, substance

use issues, and lack of vocational training.

• Institutional barriers to employment include inhospitable labor market conditions,

discrimination in hiring practices, bureaucratic red tape, and strict shelter policies.

• Evidence-based interventions for individual barriers emphasize recognizing the unique

needs and challenges of people experiencing homelessness.

• Policy recommendations for overcoming institutional barriers include “Ban the Box” and

“Ban the Address” legislation, employment-based intake questions, and hiring people with

lived experience of homelessness at service provider agencies.

Homelessness and Employment

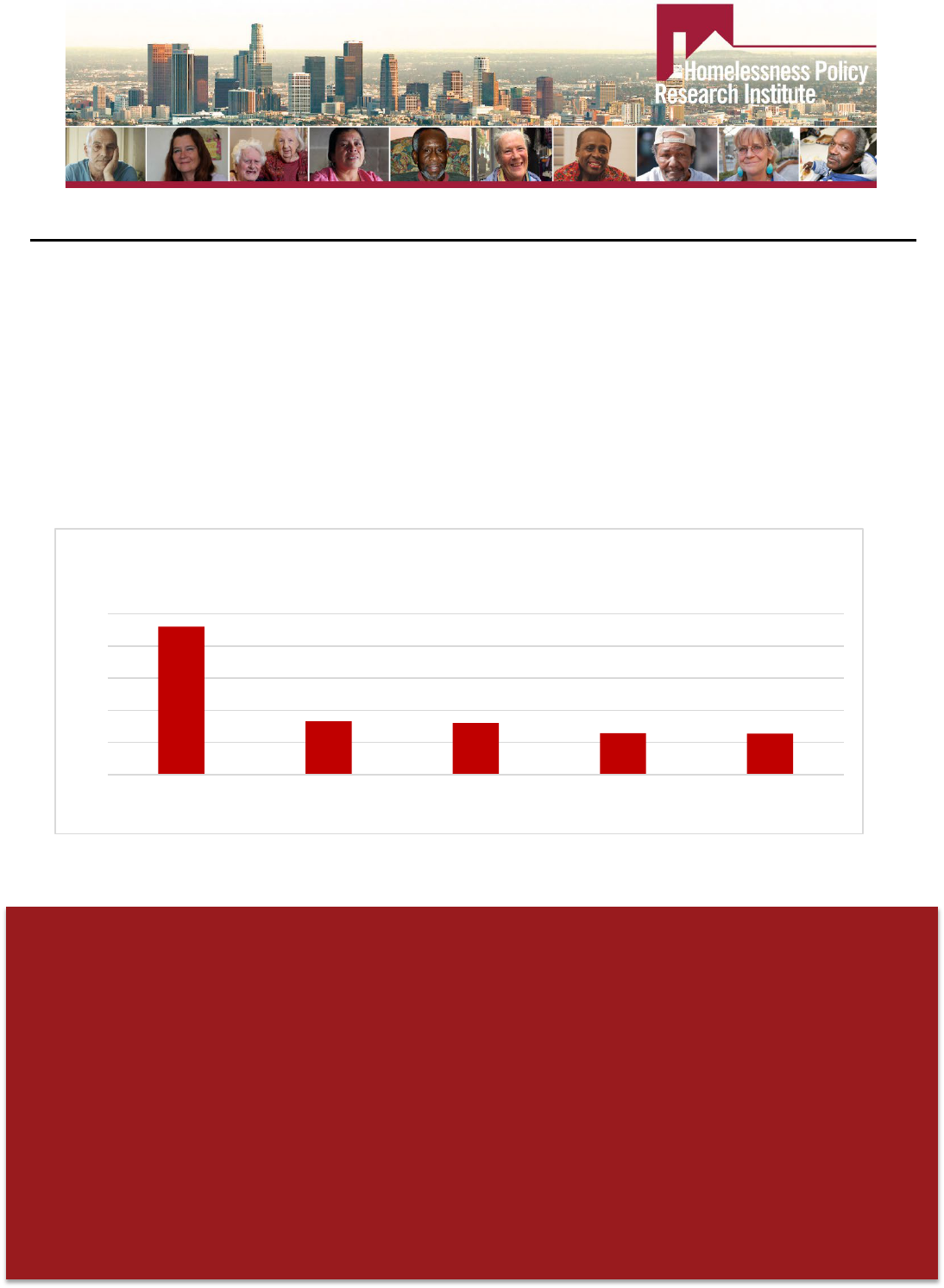

Unemployment is a prominent factor in the persistence of homelessness across the country. In Los Angeles County,

46% of unsheltered adults cited unemployment or a financial reason as a primary reason why they are

homeless (LAHSA, 2019a).

Researchers have estimated unemployment rates among people experiencing

homelessness ranging from 57% to over 90% compared to 3.6% for the general United States population (Acuña &

Ehrlenbusch, 2009; Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness, 2013; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020a).

Being unemployed while experiencing homelessness also makes it difficult to exit homelessness, and people

experiencing homelessness face a range of barriers to employment (Poremski et al., 2014). However, even though

unemployment rates are high among people experiencing homelessness, evidence also suggests that many people

experiencing homelessness want to work and, with the right supports and opportunities, can achieve positive

employment outcomes (Shaheen & Rio, 2007). This literature review will synthesize research on unemployment as

it relates to homelessness as well as promising strategies for facilitating the employment of people experiencing

homelessness.

46%

17%

16%

13%

13%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Unemployment/

financial reasons

Household

conflict

Substance

use

Breakup/

divorce

Mental health

issues

Top 5 Reasons Cited for Homelessness - Adults Experiencing Unsheltered

Homelessness in LA County (2019)

Source: LAHSA Adult Demographic Survey, 2019

Literature Review & Data Analysis

Background and Research Motivation

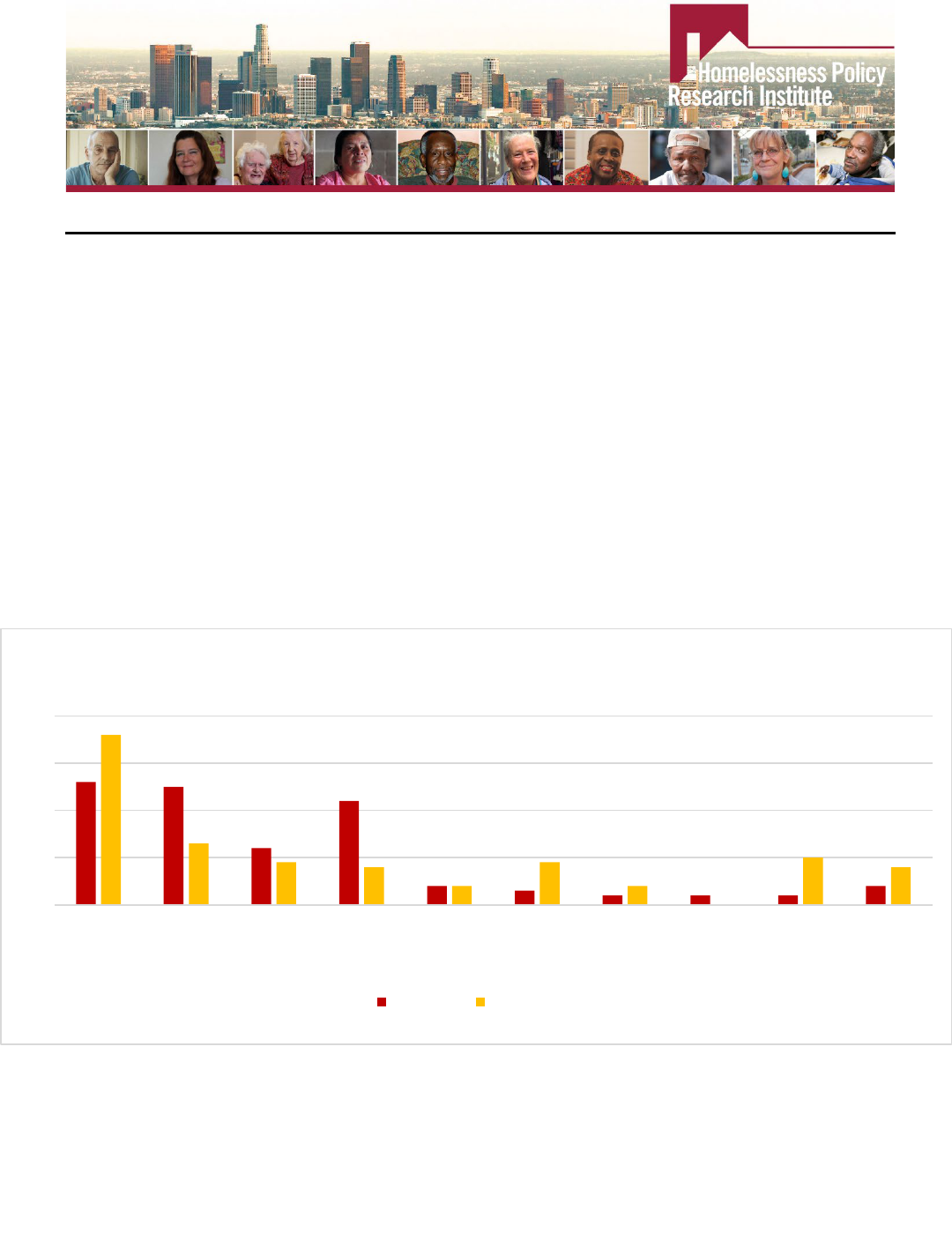

According to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s (LAHSA) 2019 Adult Demographic

Survey, over 50% of single adults (24 and older) experiencing unsheltered homelessness in Los

Angeles County are unemployed (LAHSA, 2019a). Of those unemployed, approximately half

reported that they are actively looking for work. The same survey found that 49% of unsheltered

adults in family units are unemployed, but a much higher percentage of them (36%) are actively

looking for work than single adults. Additionally, 46% of unsheltered adults cited unemployment or

a financial reason as a primary reason why they are homeless (LAHSA, 2019a). According to the

same survey, about 20% of single adults experiencing unsheltered homelessness in Los Angeles

County are working, including full-time, part-time, seasonal, and self-employment compared to

about 32% of unsheltered adults in family units (LAHSA, 2019a). Not only are people experiencing

homelessness employed at low rates, but evidence shows that those who are employed report very

low annual earnings (California Policy Lab, 2020). In Los Angeles County, employed people

experiencing homelessness earned an average of just under $10,000 in the year prior to experiencing

homelessness (California Policy Lab, 2020). The chart below details the employment statuses

reported by participants in LAHSA’s Adult Demographic Survey:

T

he unemployment rate is even higher for sheltered adults – in 2019, only 16% of adults

experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County emergency shelters and transitional housing units

reported being employed (LAHSA, 2019b). Of these not employed, over half reported that they were

actively looking for work, and one-third reported that they were unable to work (LAHSA, 2019b).

The intersection of unemployment and homelessness is particularly salient for Black people

experiencing homelessness because unemployment among Black people nationwide is already

disproportionately high due to structural and institutional racism (LAHSA, 2018). According to a

26%

25%

12%

22%

4%

3%

2% 2% 2%

4%

36%

13%

9%

8%

4%

9%

4%

0%

10%

8%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

Unemployed;

actively

looking

for work

Unemployed;

not actively

looking for

work

Self-

employed

Disabled/

on disability

Retired Part-time

employed

Full-time

employed

Temporary

worker

Seasonal

worker

Other

Employment Status of Adults Experiencing Unsheltered Homelessness in

Los Angeles County (2019)

Individuals In Family Units

Source: LAHSA Adult Demographic Survey, 2019

August 24, 2020

2

report by LAHSA’s Ad-Hoc Committee on Black People Experiencing Homelessness (2018), Black

people face systematic discrimination in the labor market based on their race and earn lower wages

than white workers on average. In January 2020, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the

national unemployment rate among Black adults was 6% compared to 3.1% among white adults,

4.3% among Latinx/Hispanic adults and 3% among Asian adults (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020b).

In March 2020, during the first month of widespread workplace closures due to the pandemic, the

Black unemployment rate rose to 6.7% compared to 4% for white adults and will likely continue to

rise as the economic impact of the pandemic deepens (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020b).

Additiona

lly, higher incarceration rates for Black and Latinx people present an additional barrier to

finding employment and housing. The incarceration rate among Black Americans is nearly six times

the incarceration rate for whites and almost double the rate for Latinx/Hispanic adults (Gramlich,

2019). Evidence suggests that formerly incarcerated individuals are more likely to be unemployed

than the general population and that incarceration history is associated with fewer types of

employment opportunities post-release (Couloute & Kopf, 2018; Cooke, 2004). Further

compounding the issue, formerly incarcerated individuals are almost ten times more likely to

experience homelessness than those without an incarceration history (Couloute, 2018). The

interaction between incarceration, institutional racism in hiring practices, and homelessness makes

Black people experiencing homelessness particularly vulnerable to unemployment (LAHSA, 2018).

Barriers to Employment

People experiencing homelessness face several barriers that make it difficult to find and maintain

employment. These include individual barriers like mental health and substance use challenges and

systemic or institutional barriers like discrimination in hiring practices and shelter regulations.

Individual barriers

Mental health challenges are a common individual barrier to securing and maintaining employment

(Poremski et al., 2014; Ferguson et al., 2012a; Radey & Wilkins, 2010). According to Perry and

Craig (2015), rates of mental health challenges, including depression

, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder,

personality disorder, self-harm, and attempted suicide are disproportionately high among people

experiencing homelessness. The same study found that rates of serious mental illness (including major

depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder) was between 25-30% amongst the population

experiencing homelessness, both sheltered and unsheltered. This finding, combined with the findings that

jobseekers with mental health challenges face difficulty securing and maintaining employment, suggest

that people experiencing homelessness with mental health challenges face a compounded set of

employment barriers.

The episodic nature of some mental illnesses makes it difficult for job seekers

with mental health challenges to be consistently available and highly functioning for work (Harris et

al., 2013). Job seekers with mental health challenges also face stigma associated with mental illness,

which can lead to low expectations of these job seekers from employers (Harris et al., 2013).

Poremski et al. (2015) found that trauma from past experiences with homelessness played a factor in

dissuading newly housed jobseekers from pursuing employment because they feared their anxieties

associated with their trauma would resurface on the job.

C

hallenges related to substance use and addiction can also pose barriers to employment for people

experiencing homelessness (Ferguson et al., 2011). Tam et al. (2003) found that consistent substance

use was negatively associated with long-term labor force participation both for the housed and

unhoused populations, but that people experiencing homelessness were more likely to have

August 24, 2020

3

substance abuse challenges than their housed peers. Survey respondents in a Canadian study of

adults experiencing homelessness with mental health issues expressed that it was difficult to hide

substance use from potential employers when searching for jobs (Poremski et al., 2014). For

employed people experiencing homelessness, substance use challenges make it difficult to maintain

employment, especially when combined with depression or other mental health challenges

(Poremski et al., 2014). Additionally, employed people experiencing homelessness who have

substance use disorders are more likely to have lower-level jobs that provide less income than those

without substance use challenges (Zuvekas & Hill, 2000).

Physical disability is also a well-documented barrier to employment for people experiencing

homelessness (Shier et al., 2012; Makiwane et al. 2010; National Coalition for the Homeless, 2009;

Long et al. 2007). Workers with disabilities – regardless of housing status – are underrepresented in

the labor force and tend to earn lower wages and hold lower-status jobs than those without

disabilities (Snyder et al., 2009). In the Los Angeles area, about 16% of all people experiencing

homelessness and 19% of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness have a physical disability

(LAHSA, 2019). In San Francisco, upwards of 23% of people experiencing homelessness reported

having a physical disability (USICH, 2018). Not only can physical disability prevent workers from

performing specific tasks, but it can also make it difficult for individuals to access worksites

(National Transitional Jobs Network, 2012b).

J

obseekers experiencing homelessness often lack vocational skills or workforce training, which

serves as an additional barrier to employment. One study found that people experiencing

homelessness are more likely to lack skillsets like

stress management, social skills, independent living

skills, and skills for vocational engagement, all of which affect an individual’s job readiness (

Muñoz et

al., 2005). Another study found that youth experiencing homelessness had low levels of educational

and vocational preparation, which negatively impacts job prospects and career mobility (Barber et

al., 2005). According to Ferguson et al. (2012), young adults experiencing homelessness are

alienated from formal employment for many reasons, including disconnection from educational and

vocational settings.

Institutional barriers

In a qualitative study based on interviews with a sample of people experiencing homelessness in

Calgary, Canada, Shier et al. (2012) make note of several features of the labor market that result in

barriers to stable employment for this population. The authors note that the commonly held belief

that stable, long-term employment is key in solving homelessness does not align with what people

experiencing homelessness actually face in the job market: temporary work, inconsistent pay, and

hostile relationships with employers (Shier et al., 2012). Furthermore, the employment opportunities

generally available to people experiencing homelessness are not only precarious but, in many cases,

undesirable, dangerous, and/or exploitative (Shier et al., 2012).

Bu

reaucratic barriers can also be factors that discourage stable employment among people

experiencing homelessness. Findings from a 2010 survey of people experiencing homelessness in

Sacramento, CA found that 35% of respondents reported things like long waiting lists, red tape, and

lack of agency follow-up as reasons why they felt employment assistance agencies were not helpful

in connecting them with work (Sacramento Steps Forward, 2010). Additionally, homeless service

systems are often not asking the right kinds of questions – specifically about the employment needs

August 24, 2020

4

and interests of job seekers experiencing homelessness – during the intake process with new clients

(Heartland Alliance, 2019).

Dis

crimination during the hiring process is a major barrier to employment for people experiencing

homelessness. Golabek-Goldman (2017) found that homeless jobseekers face discrimination in the

hiring process when they are unable to provide a home address on their applications or use the

address of a shelter. Even individuals with lived experience of homelessness who have found stable

housing face discrimination based on gaps in their work history due to previous homelessness,

mental health challenges, and substance use (Poremski et al., 2015). Criminal history is also a source

of discrimination in this context. Despite the passing in many states of “Ban the Box” legislation,

which limits the ability of employers to consider criminal record during the hiring process, many

employers still discriminate against applicants with criminal histories even if their crime is not

relevant to the job or occurred a long time ago (National Health Care for the Homeless Council,

2012). So entrenched is this practice that some homeless job seekers with criminal records report

that they avoid applying for jobs altogether because they anticipate rejection (Poremski et al., 2014).

Occupational licenses and certifications for many professions are also commonly denied to those

with criminal histories (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2018). Black people experiencing

homelessness face compounded layers of employment discrimination – one study found a 50% gap

in resume callback rates between applicants with Black-associated names and White-associated

names (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). Even companies with organizational diversity statements

were found by researchers to be no less likely to discriminate based on race during the hiring process

than companies with no diversity commitment (Kang et al., 2016).

P

oremski et al. (2014) also found that shelter regulations could serve as barriers to stable

employment for those staying in emergency shelters or temporary housing. These regulations include

strict schedules or curfews that do not make exceptions for work hours, unsatisfactory sleeping

arrangements that leave individuals unrested for their shifts, and the lack of security for personal

belongings when individuals are away from the shelter at work (Poremski et al., 2014).

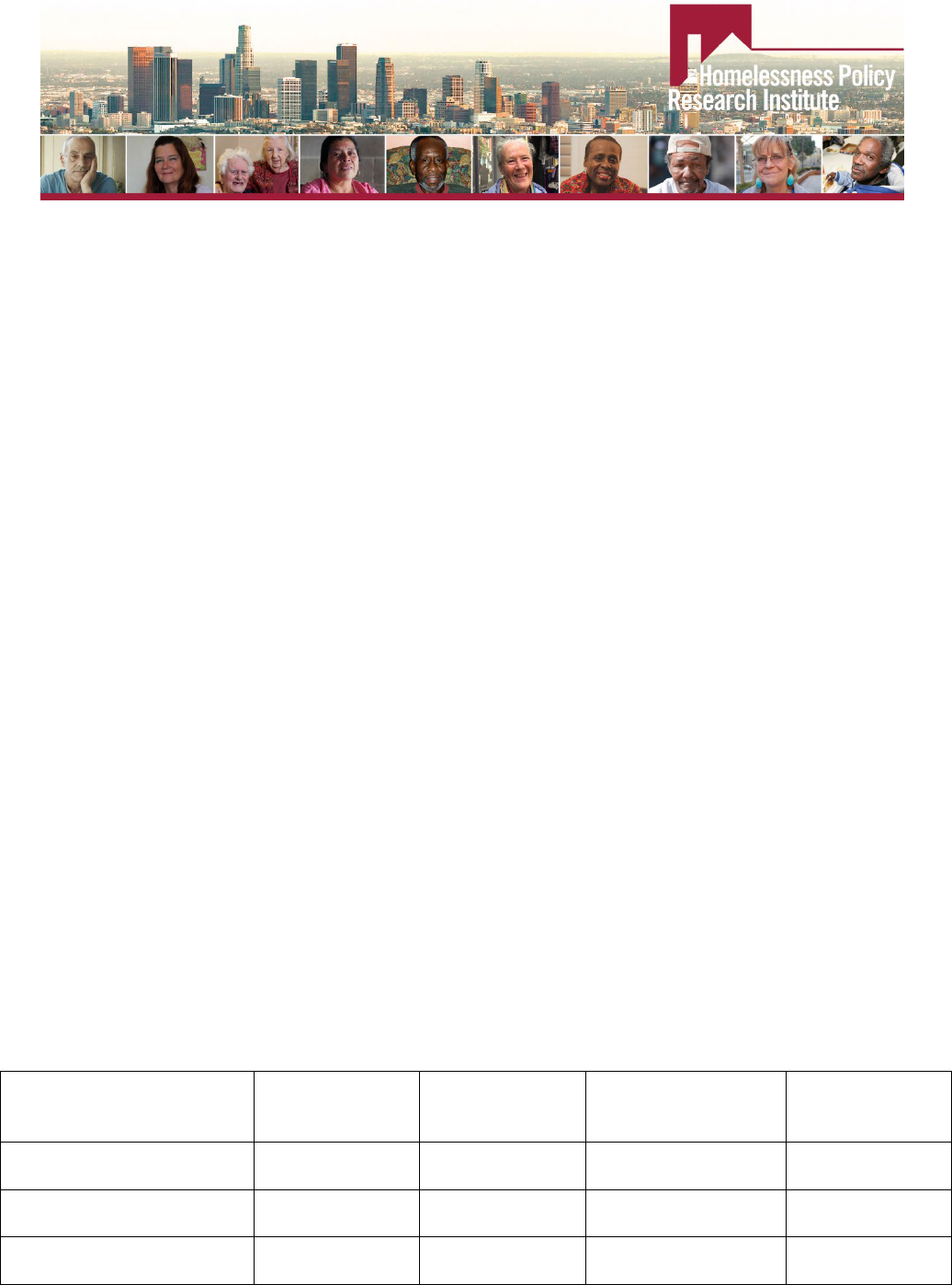

Intervention Strategies

A number of interventions exist that are designed to improve job readiness and employment

outcomes for people experiencing homelessness who have disabling conditions like mental health

and substance use challenges as well as physical health and disability issues. Four promising

interventions are: 1) individual placement and support, 2) the social enterprise intervention, 3) work

skills training programs, and 4) transitional jobs programs. The following chart compares the

features of the four the models, and more detail on each intervention follows the chart:

Program Features

Individual

Placement and

Support (IPS)

Social Enterprise

Intervention

(SEI)

Moving Ahead

Program (MAP)

Work Skills Training

Transitional Jobs

(TJ) Programs

Focus on permanent

employment

x x x

Focus on temporary,

transitional employment

x

Clinical mental health

services

x x

August 24, 2020

5

Vocational skills training /

courses

x x x

Client assessment pre-

program participation

x x

Focus on rapid employment

(no assessment period)

x

Post-program follow-up and

support

x x x

Internship / real work

placement built into

program

x x x

I

ndividual Placement and Support

Also known as “supported employment,” individual placement and support (IPS) is an evidence-

based practice aimed at improving employment outcomes for job seekers with severe mental illness

A 2004 study found that 40-60% of people enrolled in supported employment programs get a job,

compared with just 20% of similar individuals (Bond, 2004). While not specifically designed for

people experiencing homelessness with severe mental illness, the intervention has been used for

homeless jobseekers and has yielded positive outcomes (Leddy et al., 2014; Ferguson, 2013).

Ferguson (2017) even found that IPS resulted in positive non-vocational outcomes among homeless

youth with mental illness, including increased self-esteem, housing stability, and decreased attention

deficit problems.

T

he components of IPS are as follows (Bond, 2004):

• Services focused on competitive employment – the goal is to help participants obtain and maintain

permanent competitive jobs as opposed to day treatment or sheltered work;

• Eligibility based on consumer choice – the only requirement for inclusion in an IPS program is a desir

e

to

work in a competitive job. Job seekers will not be excluded due to mental or physical health

challenges, substance use challenges, lack of job-readiness, or disability;

• Rapid job search – IPS programs avoid lengthy pre-assessment and training periods to expedite the job

search process;

• Integration of rehabilitation and mental health – IPS program staff meet and interact regularly with

treatment teams that work with the jobseekers;

• Attention to consumer preferences – IPS program staff works with job seekers to find individualize

d

j

obs based on job seeker preference, strengths, and work experience;

•

Time-unlimited and individualized support – IPS programs continue to support clients even after they

have found employment and are individualized to the specific situation of each worker/jobseeker.

Soc

ial Enterprise Intervention

Another evidence-based intervention for helping people experiencing homelessness find and

maintain employment is the Social Enterprise Intervention (SEI). The model has been used with both

adults and youth experiencing homelessness, both with and without mental illness (Ferguson, 2013).

A social enterprise is a revenue-generating venture established to create positive social impact, and

the SEI model equips people experiencing homelessness to establish their own social enterprises

(Ferguson, 2013). In the context of youth experiencing homelessness, SEI seeks to divert homeless

youth away from high-risk behaviors like substance use and crime by engaging them in vocational

August 24, 2020

6

training and mental health services (Ferguson, 2013). In addition to providing youth with vocational

and business skills, research suggests that SEI improves life satisfaction, family contact, peer

support, depressive symptoms, and linkages to services among these youth (Ferguson 2007;

Ferguson & Xie, 2007). A 2013 study found that 67% of young people enrolled in an SEI program

remained employed ten months after the completion of an SEI program, compared to just 25% of a

similar control group (Ferguson, 2013).

T

he SEI model lasts 20 months and has four stages (Ferguson, 2013):

• Vocational skills acquisition – a four-month course in which youth receive education and technical

training concerning specific vocational skills;

• Small-business skills acquisition – a separate four-month course on business-related skills such as

accounting, budgeting, marketing, and management;

• Social enterprise formation and distribution – a year-long stage in which participating youth establish

a

social enterprise in a supportive, empowering, and community-based setting;

• Clinical services – mental health services provided by a clinician and/or case managers, interwoven

across the entire 20-month peri

od.

W

ork Skills Training Programs

The first part of the SEI model, the vocational skills acquisition course, can be an intervention on its own. A

notable example of a successful work skills training program is the Moving Ahead Program (MAP), utilized by

New England homelessness service provider St. Francis House. An evaluation of the program found that six

months after completion, participants showed improvements in employment, housing stability, general health

status, substance use, self-esteem and self-efficacy, and criminal justice system involvement (Nelson et al.,

2012). Eighty-four percent of participants maintained some level of employment after graduation, in

comparison to just 52% of the same sample without the work skills program (Nelson et al., 2012). The

evaluation also revealed that there is an association between improvements in work skills and improvements in

self-esteem and self-efficacy, which then predicted stable housing situations (Nelson et al., 2012).

The phases of MAP are as follows (Nelson et al., 2012):

• Strengths and abilities assessment – five-day program to explore job seeker strengths, weaknesses,

abilities, and interests;

• Regular class meetings – participants attend class five days per week for 14 weeks. Class sizes ar

e

s

mall, generally with 12-15 individuals. Each week of class focuses on a different subject, ranging from

career exploration, to career goal-setting, to appropriate workplace behavior;

• Internship – after classes are complete, a partner employment agency arranges a 6-week internship for

participants;

• Post-graduation – the employment agency continues to assist participants in searching for employment

after the completion of the program

.

T

ransitional Jobs Programs

Another promising intervention is the Transitional Job (TJ) model, which connects job seekers experiencing

homelessness with temporary, competitive jobs that combine real work with skill development and supportive

services (National Transitional Jobs Network (NTJN), 2012a). Unlike the IPS model, which is not time-limited,

August 24, 2020

7

TJ programs are intended to be temporary and act as a stepping-stone for participants entering the labor market

(NTJN, 2012). The TJ model is appealing to service providers because it generally operates as a form of

subsidized public or private employment, and thus is ideal for participants receiving benefits like Temporary

Assistance for Needy Family (TANF) (Baider & Frank, 2006). TJ programs aim to help participants begin work

as quickly as possible and typically offer a nurturing work environment, additional training, and enhanced

connections to other services that help job seekers experiencing homelessness succeed in the labor market after

they have transitioned out of their temporary job (Baider & Frank, 2006). An analysis of one such program at

Central City Concern’s Employment Access Center in Portland, Oregon, found that 71 percent of participants

obtained employment while part of the program, and that 77 percent of these participants who found

employment remained employed nine months later (NJTN, 2012).

The core program elements of a TJ program include (NTJN, 2012):

• Orientation & assessment – individualized approach that identifies participant strengths and barriers;

• Job readiness and life skills classes – vocational skills training to support successful workplace

behaviors;

• Employment-focused case management – helps participants coordinate services and manage individual

barriers;

• A transitional job – the program connects each participant with a transitional job, which provides real,

wage-paying work experience and development of vocational skills;

• Unsubsidized job placement and retention – program helps participants find a job in the labor force t

o

r

eplace their temporary job and then provides support to help participants stay in that job;

• Linkages to education and training – supports further career and skills development.

J

ob Coaches

Evidence suggests that jobseekers experiencing homelessness are more likely to find and sustain competitive

employment if they have access to a job coach (Hoven et al., 2016). Support from a job coach improves

employment outcomes for all age groups but is especially impactful with homeless jobseekers under the age of

25 years old (Hoven et al., 2016). Evidence also suggests that receiving support from a job coach may

strengthen the jobseeker’s motivation to continue applying for jobs even after rejections (Hoven et al., 2016).

Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Barriers

Whereas the above intervention strategies are designed to help job seekers experiencing

homelessness overcome individual barriers to employment, researchers and practitioners also

recommend policy reforms to address institutional and structural barriers to employment for people

experiencing homelessness.

Ban the Box / Ban the Address

“Ban the Box,” or fair chance hiring legislation, which prevents employers from asking job seekers

about their criminal history on job applications, exists in 35 states and over 150 cities and counties

across the country (National Employment Law Project (NELP), 2019). However, in about two-thirds

of these states and municipalities, the legislation only applies to public-sector jobs (NELP, 2019). A

federal ban the box policy and an expansion of this type of legislation to the private sector will help

jobseekers experiencing homelessness who have criminal histories secure employment.

August 24, 2020

8

A “Ban the Address” policy, which would remove questions about home address on job applications,

is similar to ban the box but is specifically intended to support jobseekers experiencing homelessness

(Golabek-Goldman, 2017). In addition, businesses, government agencies, and non-profit

organizations can create programs where they provide P.O. boxes or mailing addresses for job

applicants who are experiencing homelessness (Golabek-Goldman, 2017).

E

nhancing Mainstream Social Services

According to Shaheen and Rio (2007), access to mainstream, federally funded employment

resources has not kept pace with the urgent need for services among people experiencing

homelessness. In other words, communities and states have difficulty accessing funding for

employment services, which could come from mainstream employment programs like vocational

rehabilitation programs, Workforce Investment Act-funded employment services, Community

Services Block Grants, Mental Health and Substance Abuse Block Grants, and Medicaid (Shaheen &

Rio, 2007). States and communities must do a better job of prioritizing employment as a solution to

homelessness and leverage federal dollars towards this end.

L

os Angeles County is directing funding towards employment programs for people experiencing

homelessness, including bolstering the CalWORKs subsidized employment program for homeless

families and supporting social enterprise interventions for adults (Los Angeles County Homeless

Initiative, 2016). In 2019, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors established a Homeless

Employment Innovation Fund, which includes funding for stipends for homeless participants in

vocational training programs and performance-based innovation funds for America's Job Centers of

California (Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, 2019). Additionally, the County is working to

strengthen coordination between departments, including the Department of Public Social Services

and the Department of Workforce Development, Aging and Community Services (Los Angeles

County Homeless Initiative, 2019).

C

oordinated Entry System Intake Questions

HUD mandates that continuums of care use a centralized, coordinated intake process, widely known

as a coordinated entry system (CES) for their homeless services systems (HUD, 2015). The CES

intake process involves an assessment of each individual’s needs and preferences to connect them

with the appropriate housing and homeless services. However, CES assessments do not necessarily

address the employment needs and preferences of people seeking homeless services (Heartland

Alliance, 2019). Continuums of care can add questions about employment history and preferences to

their CES assessments to better connect people experiencing homelessness with vocational training

programs, subsidized employment programs, or job coaches (Heartland Alliance, 2019).

Hir

ing People with Lived Experience at Service Provider Agencies

One way that service provider agencies can addressing discrimination in the hiring process is to

institute policies that ensure that lived experience of homelessness is a desired and valued

qualification in the hiring process (LAHSA, 2018). By bringing in people who have experienced

homelessness in the past, service provider agencies can start to shift at an organizational level

towards a system that does not discriminate against those who are currently homeless, or those with

substance use and/or mental and physical health challenges. Having people with lived experience on

staff also helps create mentorship relationships and peer support networks that can help boost self-

esteem and determination among job seekers experiencing homelessness (Heartland Alliance, 2017).

August 24, 2020

9

Flexible Shelter Policies

To address the barriers to employment that strict shelter rules pose, shelter providers can institute

policies that allow for a more flexible schedule that allows people to build their days around

meaningful activities like employment (Poremski et al., 2014). Shelters could provide exceptions to

curfew rules to those who have night jobs or whose hours conflict with the curfew. Shelters can also

provide secure lockers for the personal belongings of those who have jobs or are actively seeking

work so that they can leave the shelter without fearing for the theft of their belongings.

This literature review was developed by:

Ian Gabriel, Elly Schoen, Victoria Ciudad-Real, and Allan Broslawsky

August 24, 2020

10

For questions about the Homelessness Policy Research Institute,

please contact Elly Schoen at [email protected]

References

Acuña, J., & Ehrlenbusch, B. (2009). Homeless Employment Report: Findings and

Recommendations. Retrieved from

https://www.nationalhomeless.org/publications/homelessemploymentreport/index.html

B

aider, A., & Frank, A. (2006). Transitional Jobs: Helping TANF Recipients with Barriers to

Employment Succeed in the Labor Market. Retrieved from

https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/files/0296.pdf

B

arber, C. C., Fonagy, P., Fultz, J., Simulinas, M. A., & Yates, M. (2005). Homeless Near a

Thousand Homes: Outcomes of Homeless Youth in a Crisis Shelter. American Journal of

Orthopsychiatry, 75(3), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.75.3.347

B

ertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and

Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination. American Economic

Review, 94(4), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828042002561

B

ond, G. R. (2004). Supported Employment: Evidence for an Evidence-Based Practice. Psychiatric

Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.2975/27.2004.345.359

C

alifornia Policy Lab. (2020). Employment and Earnings Among LA County Residents Experiencing

Homelessness. Retrieved from

https://www.capolicylab.org/wp-

content/uploads/2020/02/Employment-Among-the-Homeless-in-Los-Angeles.pdf

C

ooke, C. L. (2004). Joblessness and Homelessness as Precursors of Health Problems in Formerly

Incarcerated African American Men. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(2), 155–160.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04013.x

C

ouloute, L. (2018). Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. Retrieved

from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/housing.html

Couloute

, L., & Kopf, D. (2018). Out of Prison & Out of Work: Unemployment among formerly

incarcerated people. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html

F

erguson, K. (2007). Implementing a Social Enterprise Intervention with Homeless, Street-Living

Youths in Los Angeles. Social Work, 52(2), 103–112. Retrieved from

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23721164?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

F

erguson, K. M. (2013). Using the Social Enterprise Intervention (SEI) and Individual Placement

and Support (IPS) Models to Improve Employment and Clinical Outcomes of Homeless

Youth With Mental Illness. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(5), 473–495.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2013.764960

F

erguson, K. M. (2017). Nonvocational Outcomes From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Two

Employment Interventions for Homeless Youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(5),

August 24, 2020

11

603–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517709076

Ferguson, K. M., Bender, K., Thompson, S. J., Maccio, E. M., & Pollio, D. (2011). Employment

Status and Income Generation Among Homeless Young Adults. Youth & Society, 44(3),

385–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x11402851

Ferguson, K. M., & Xie, B. (2007). Feasibility Study of the Social Enterprise Intervention With

Homeless Youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(1), 5–19.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507303535

Ferguson, K. M., Xie, B., & Glynn, S. (2011). Adapting the Individual Placement and Support

Model with Homeless Young Adults. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(3), 277–294.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-011-9163-5

Golabek-Goldman, S. (2017). Ban the Address: Combating Employment Discrimination Against the

Homeless. The Yale Law Journal, 126(6), 1788–1868. Retrieved from

https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/h.1788.Golabek-Goldman.1868_9wo15f6u.pdf

Gramlich, J. (2019). The gap between the number of blacks and whites in prison is shrinking.

Retrieved from

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/30/shrinking-gap-between-

number-of-blacks-and-whites-in-prison/

Harris, L. M., Matthews, L. R., Penrose-Wall, J., Alam, A., & Jaworski, A. (2013). Perspectives on

barriers to employment for job seekers with mental illness and additional substance-use

problems. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(1), 67–77.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12062

Heartland Alliance. (2017). Creating Economic Opportunity for Homeless Jobseekers - The Role of

Employers and Community-Based Organizations. Retrieved from

http://nationalinitiatives.issuelab.org/resource/creating-economic-opportunity-for-homeless-

jobseekers-the-role-of-employers-and-community-based-organizations.html

Heartland Alliance. (2019). How and Why to Integrate Income & Employment-Related Questions

Into Coordinated Entry Assessments. Retrieved from

http://nationalinitiatives.issuelab.org/resource/how-and-why-to-integrate-income-

employment-related-questions-into-coordinated-entry-assessments.html

Hoven, H., Ford, R., Willmot, A., Hagan, S., & Siegrist, J. (2016). Job Coaching and Success in

Gaining and Sustaining Employment Among Homeless People. Research on Social Work

Practice, 26(6), 668–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514562285

Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness. (2013). The High Stakes of Low Wages:

Employment among New York City’s Homeless Parents. Retrieved from

https://www.icphusa.org/wp-

content/uploads/2013/05/ICPH_policybrief_TheHighStakesofLowWages_2013.pdf

Kang, S. K., DeCelles, K. A., Tilcsik, A., and Jun, S. (2016). Whitened resumes: Race and self-

August 24, 2020

12

presentation in the labor market. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(3), 469-502.

Retrieved from

http://www-

2.rotman.utoronto.ca/facbios/file/Whitening%20MS%20R2%20Accepted.pdf

Leddy, M., Stefanovics, E., & Rosenheck, R. (2014). Health and well-being of homeless veterans

participating in transitional and supported employment: Six-month outcomes. Journal of

Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(1), 161–174.

https://doi.org/10.1682/jrrd.2013.01.0011

Long, D., Rio, J., & Rosen, J. (2007). Employment and Income Supports for Homeless People.

Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/p11.pdf

Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. (2019). Employment Innovations to Link Homeless

Individuals to Jobs. Retrieved from

http://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/134478.pdf

Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative. (2016). Approved Strategies to Combat Homelessness.

Retrieved from

https://homeless.lacounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/HI-Report-

Approved2.pdf

Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative. (2019). Employment and Homelessness Taskforce

Recommendations Overview. Retrieved from

https://homeless.lacounty.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2019/11/EHT-materials.pdf

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2019a). Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Adult

Demographic Survey.

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2019b). Homeless Management Information System

Data, Los Angeles Continuum of Care (LA CoC HMIS).

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2018). Reports and Recommendations of the Ad-Hoc

Committee on Black People Experiencing Homelessness. Retrieved from

https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=2823-report-and-recommendations-of-the-ad-hoc-

committee-on-black-people-experiencing-homelessness

Makiwane, M., Tamasane, T., & Schneider, M. (2010). Homeless individuals, families and

communities: The societal origins of homelessness. Development Southern Africa, 27(1),

39–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350903519325

Muñoz, J., Reichenbach, D., & Witchger Hansen, A. (2005). Project Employ: engineering hope and

breaking down barriers to homelessness. Work, 241–252. Retrieved from

https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16179773

National Coalition for the Homeless. (2009). Employment and Homelessness. Retrieved from

https://www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/employment.html

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2018). Barriers to Work: Improving Employment in

August 24, 2020

13

Licensed Occupations for Individuals with Criminal Records. Retrieved from

http://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/Labor/Licensing/criminalRecords_v06_web.pdf

National Employment Law Project. (2019). Ban the Box. Retrieved from

https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-

content/uploads/Ban-the-Box-Fair-Chance-State-and-Local-Guide-July-2019.pdf

National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2012). Criminal Justice, Homelessness & Health.

Retrieved from

http://www.antoniocasella.eu/nume/homelessness_2011.pdf

National Transitional Jobs Network. (2012a). Employment Program Models for People Experiencing

Homelessness: Different approaches to program structure. Retrieved from

https://www.issuelab.org/resource/employment-program-models-for-people-experiencing-

homelessness-different-approaches-to-program-structure.html

National Transitional Jobs Network. (2012b). Populations Experiencing Homelessness: Diverse

barriers to employment and how to address them. Retrieved from

https://www.issuelab.org/resources/16924/16924.pdf

Nelson, S. E., Gray, H. M., Maurice, I. R., & Shaffer, H. J. (2012). Moving Ahead: Evaluation of a

Work-Skills Training Program for Homeless Adults. Community Mental Health Journal,

48(6), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9490-5

Perry, J., & Craig, T. K. J. (2015). Homelessness and mental health. Trends in Urology & Men’s

Health, 6(2), 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/tre.445

Poremski, D., Whitley, R., & Latimer, E. (2014). Barriers to obtaining employment for people with

severe mental illness experiencing homelessness. Journal of Mental Health, 23(4), 181–185.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.910640

Poremski, D., Woodhall-Melnik, J., Lemieux, A. J., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015). Persisting Barriers

to Employment for Recently Housed Adults with Mental Illness Who Were Homeless.

Journal of Urban Health, 93(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-015-0012-y

Radey, M., & Wilkins, B. (2010). Short-Term Employment Services for Homeless Individuals:

Perceptions from Stakeholders in a Community Partnership. Journal of Social Service

Research, 37(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.524513

Sacramento Steps Forward. (2010). 2010 Homeless Employment Report: Findings and

Recommendations. Retrieved from

https://www.nationalhomeless.org/advocacy/economic/sacemployment2010.pdf

Shaheen, G., & Rio, J. (2007). Recognizing Work as a Priority in Preventing or Ending

Homelessness. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(3–4), 341–358.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0097-5

Shier, M. L., Jones, M. E., & Graham, J. R. (2012). Employment Difficulties Experienced by

Employed Homeless People: Labor Market Factors That Contribute to and Maintain

August 24, 2020

14

Homelessness. Journal of Poverty, 16(1), 27–47.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2012.640522

Snyder, L. A., Carmichael, J. S., Blackwell, L. V., Cleveland, J. N., & Thornton, G. C., III. (2009).

Perceptions of Discrimination and Justice Among Employees with Disabilities. Employee

Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 22(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-009-9107-5

Tam, T. W., Zlotnick, C., & Robertson, M. J. (2003). Longitudinal Perspective: Adverse Childhood

Events, Substance Use, and Labor Force Participation Among Homeless Adults. The

American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29(4), 829–846.

https://doi.org/10.1081/ada-

120026263

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020a). Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population

Survey. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020b). The Employment Situation – March 2020.

Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). Coordinated Entry Policy

Brief. Retrieved from

https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/Coordinated-

Entry-Policy-Brief.pdf

United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2018). Homelessness in America: Focus on

Chronic Homelessness Among People With Disabilities. Retrieved from

https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Homelessness-in-America-Focus-on-

chronic.pdf

Zuvekas, S. H., & Hill, S. C. (2000). Income and employment among homeless people: the role of

mental health, health and substance abuse. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and

Economics, 3(3), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhp.94

August 24, 2020

15